This is part of an ongoing series of stories exploring rye, the crop, as it becomes Rye, the whisky.

Rye as a crop is older than the pyramids. It might have filled the bellies of the very first farmers as the last ice age was melting.

Other stories in this series:

- More producers start growing rye as crop prepares for a recovery

- Farmer finds new uses for old crop of rye

- Growing rye for seed is quirky but fun

It spread with the earliest human civilizations and cut out a place for itself for thousands of years in harsh places where other crops, such as wheat, oats and barley, had a tougher time thriving.

The Germanic barbarians who savaged Rome, the Saxon invaders who crushed the Celts and the Vikings who raided and conquered much of England, Ireland, Normandy and Russia were all likely fuelled by bellies full of crudely ground rye bread.

The crop travelled with the English settlers to the first North American colonies, hardy in the face of the cool conditions of the Atlantic seaboard. It perhaps caused the Salem witch persecutions of Massachusetts with ergot-infected bread leading to hallucinations among the Puritans.

It provided bread to early Canadian settlers who did not yet have wheat varieties that could well handle the tough Canadian conditions. Even as Red Fife and other wheat varieties replaced rye in most Canadians’ hearts and bellies, waves of eastern European immigrants brought their love of pungent pumpernickel to both east and the Prairies.

Despite prohibition and temperance — or because of them — Canadian “rye” whisky became not just a Canada-wide tipple but a major player in the speakeasies of the Roaring Twenties and later.

In Canada rye faded and fell out of farmers’ rotations as prices plummeted due to declining interest in the bread. As well, breeding failed to keep up with other crops as they became easier to market.

However, in central and eastern Europe rye remained strong and central to people’s diets, spurring breeding companies to develop hardy and high-yielding hybrid varieties, keeping farmers there committed to the crop.

Those hybrids have hit North America, allowing farmers to grow the crop with confidence, while a Rye revival has begun in the North American whisky world with the mostly ignored family of uisce beatha (Irish for “water of life”) regaining some of its former splendour with distillers celebrating the unique spiciness of the ancient crop.

Rye, as a crop, began its epic journey perhaps 13,000 years ago, and there are no signs of it fading.

Crop archaeologists believe the earliest rye cultivation might have been abandoned at the end of the last ice age as climate change allowed early wheat, barley and oat varieties a better chance to thrive among early civilizations.

With another era of climate change upon the Earth, rye could see itself regain even more prominence. Its resilience and ability to handle challenging conditions make it as attractive to today’s farmers as it did to the pre-pottery Neolithic farmers we can only glimpse through the mists of time.

Charting the spread of rye:

11000 BC: Abu Hureya, northern Syria: Evidence that late Pleistocene humans may have cultivated wild rye varieties, creating the first domesticated crop. However, many experts do not accept this.

6600 BC: Can Hasan III, central Turkey: Domesticated rye being grown and ground by Neolithic farmers.

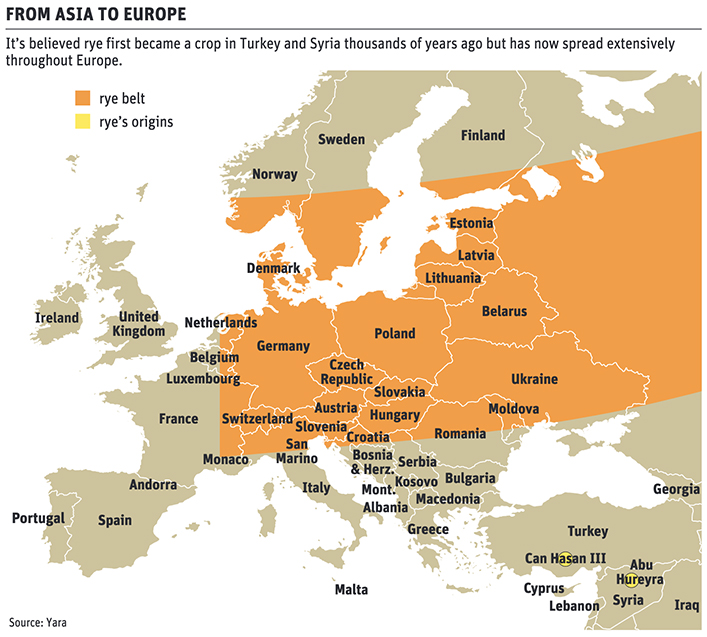

600-500 BC: Black Sea region & Germany: Rye spreads north and west into cooler and wetter regions. In coming centuries rye becomes a dominant crop in what is still the rye belt of central, northern and eastern Europe because its hardy nature makes it ideal for the climate.

1500-1800 AD: North American colonies: Rye is brought by European colonists as a foundational crop.

1692: Salem, Massachusetts: Rye ergot fungus may have been responsible for the hallucinations leading to the Salem witch trials.

1880s-present: Central and eastern Europe: Rye remains an important food crop.

Late 19th century: Canada: Rye is a significant food crop, thriving in the country’s cold and challenging conditions.

1910s-1940s: Canada/United States: Rye becomes synonymous with Canadian whisky, which plays a crucial role in keeping millions of Americans “wet” during prohibition. Bootleggers and smugglers bring in Canadian liquor along much of the international border, including dozens of towns on the southern edge of the Canadian Prairies.

Hundreds of thousands of central and eastern European immigrants arrive, bringing their love for the taste of rye bread to Canada, strengthening demand. Simultaneously, wheat varieties are developed and allow for whiter breads and better bread-making characteristics, pushing rye bread out of the diet of millions of Canadians of western European origin. Over time, rye bread occupies a smaller and smaller part of the bakery shelf.

1940s-present: Canada: Rye becomes a crop primarily used for animal feed, both as silage and grain. Only a small portion is used for distilling and domestic bread-making. Exports take a significant proportion of the crop to places where the crop is more highly valued.

Today: U.S.: Rye experiences newfound popularity in whisky circles, valued for its spicy flavour and connection to early colonial history.

Europe: The crop remains a mainstay food crop in central and eastern Europe as well as Scandinavia. Use in biofuel production sees increased interest.

Canada: New European hybrid rye varieties make the crop more competitive, increasing farmer interest in growing it. Rye demand from U.S. and Canadian distillers provides a premium market for a small number of producers. Descendents of eastern European and Jewish immigrants across North America keep rye bread demand alive.