Analysts believe that rather than bolster domestic supplies and cool off prices, the measure could reduce wheat acres

Analysts think Russia’s new permanent wheat export tax may backfire.

Russia announced it plans to implement a new floating permanent tax on June 2.

The tax will be 70 percent of the difference between the export price and US$200 per tonne. So if the export price is $300, that would amount to a $70 tax.

The goal is to bolster domestic supplies of the crop and cool off prices.

Andrey Sizov, managing director of SovEcon, thinks the tax could be bullish for 2021-22 wheat price prospects.

Read Also

South American soybeans will have less impact on canola

South American production will, as usual, affect the global oilseed market, but Canadian canola is on the outside looking in until it can get China back or find alternative buyers.

It is likely to lead to a reduction in Russia’s spring wheat plantings, resulting in an estimated 1.5 to two million tonne drop in SovEcon’s initial 2021 wheat crop estimate of 77.7 million tonnes.

SovEcon had been anticipating an increase in spring acres due to strong prices and the need to replant some of the winter wheat crop.

Sizov believes the tax will cause a sharp reversal in the uptrend in Russia’s wheat production, starting with the spring wheat crop and then followed by a five to 10 percent decline in winter wheat acres in the fall of 2021.

That is because the tax will take from $1.50 to $2.30 per bushel out of the pockets of Russian farmers based on export prices ranging from $280 to $320 per tonne.

If Sizov is correct, the tax is going to have the opposite effect that the government is hoping for by restricting domestic supplies of wheat.

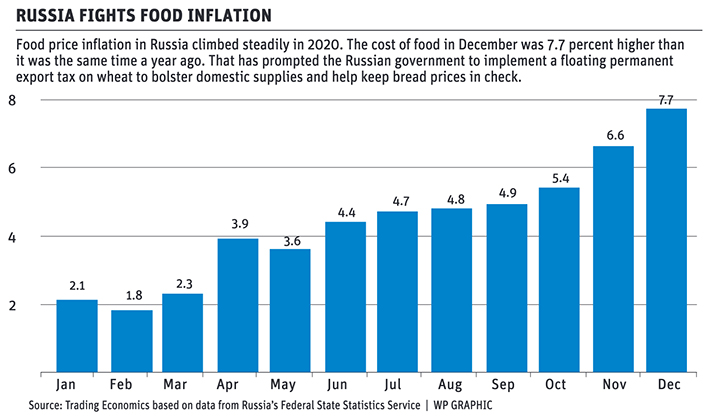

It is in response to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s concerns about rising food price inflation.

MarketsFarm analyst Bruce Burnett said politicians around the world are acutely aware of how rising food prices can quickly dethrone sitting governments.

The Arab Spring uprisings of 2010 were partially a response to rising grain prices in that region of the world.

Reuters reports that Putin is particularly concerned about high pasta prices. Many Russian families are being forced to eat what he calls “navy-style macaroni,” which is a Soviet-era dish of pasta topped with fried canned meat.

Burnett said the Russian government is attempting to prevent “a runaway freight train” on domestic wheat prices.

But he agrees with Sizov that the unintended consequence will likely be that the tax hurts the country’s spring wheat production prospects.

“When you set out a policy to keep prices low and farmers respond by not planting as much, you’re sort of shooting yourself in the foot,” he said.

“These types of policies rarely work well. They may achieve the desired impact in the short-term but in the longer term it just makes things more difficult.”

Russia’s export tax is a bit of a head-scratcher when looking only at the statistics. The United States Department of Agriculture said the country produced 85.3 million tonnes of wheat, the largest crop in the post-Soviet era.

“They obviously had some quality issues with it that kept supplies lower,” said Burnett.

Russia’s initial response was to announce that it was implementing an export quota of 17.5 million tonnes on wheat, rye, barley and corn that will be in effect from Feb. 15 to June 30.

Wheat exported within that quota was initially going to face an export tax of US$30 per tonne during that time period. Anything above the quota would face a tax of 50 percent but not less than US$121 per tonne.

On Jan. 15, the Russian government announced its intention to raise the wheat tax to US$60 per tonne between March 1 and June 30. That pushed wheat prices even higher.

Then came the announcement of the permanent floating tax.

Russia has a history of periodically implementing export taxes to keep domestic prices under control. But this latest measure is something different.

“The idea of it being permanent is maybe the new wrinkle in it,” said Tom Steve, general manager of the Alberta Wheat Commission.

He thinks a permanent tax could cause concerns for customers of the world’s biggest wheat exporter.

“If it was to be a permanent measure it obviously provides opportunities for other exporters to capitalize on those markets,” said Steve.

But he noted that Russia has also implemented a similar export tax on corn and barley; only the formula for that tax will be 70 percent of the export price minus $185 per tonne.