There is more private irrigation than there is through districts, where landowners benefit from shared infrastructure

OUTLOOK, Sask. — Demand for irrigation services in Saskatchewan has climbed sharply in the last few years, led by private irrigators who see greater opportunities from their land.

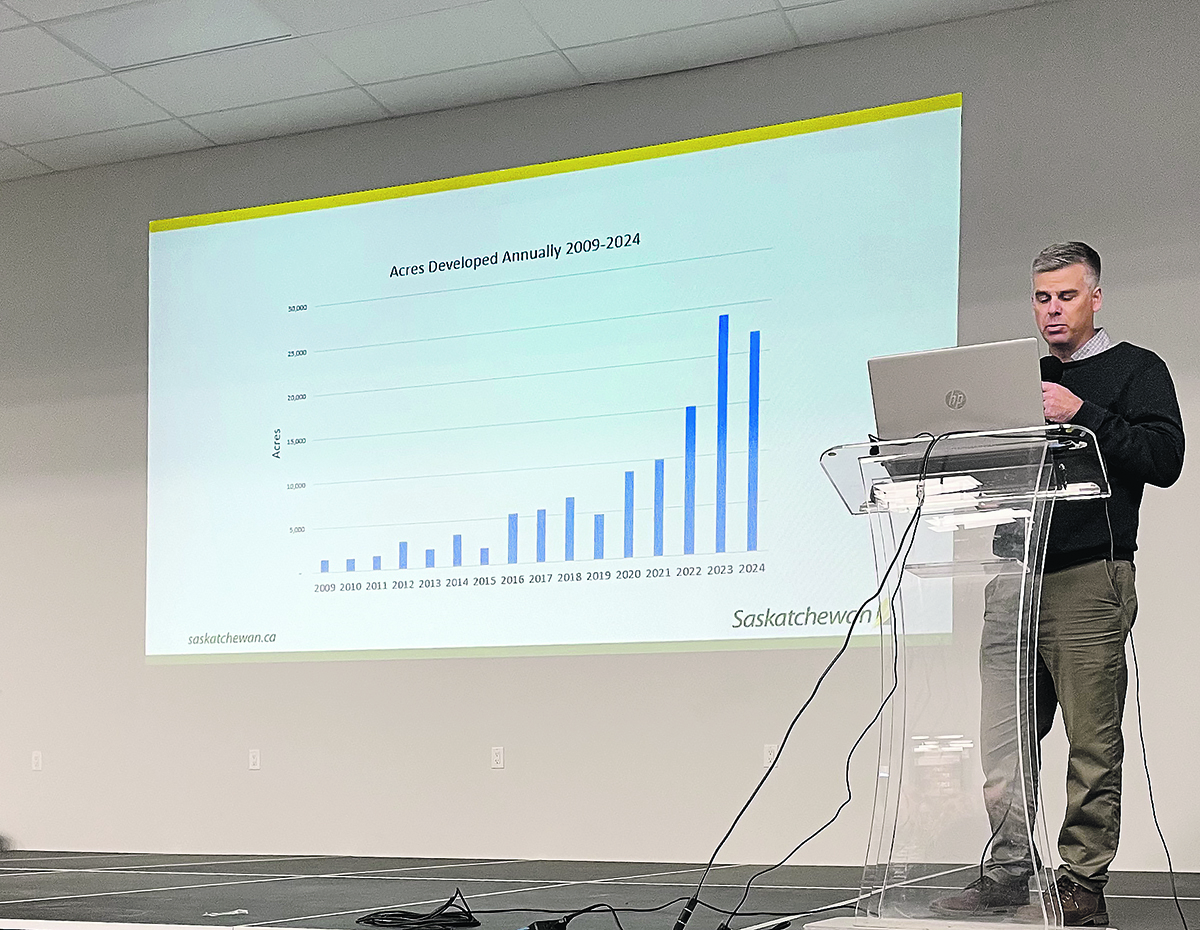

Kelly Farden, irrigation agronomy services manager with the provincial agriculture ministry, said the number of certified acres has more than quadrupled in the last eight years.

He told a November workshop that governments began investing once again in irrigation development in 2009 through federal-provincial programs in the policy frameworks.

Read Also

Canadian Food Inspection Agency red tape changes a first step: agriculture

Farm groups say they’re happy to see action on Canada’s federal regulatory red tape, but there’s still a lot of streamlining left to be done

New acres remained steady at around 5,000 per year until 2016 and then began to grow. By 2020, the number reached 8,000 new acres, then 10,000 and then 15,000.

In 2023, new acres totalled 24,000.

The ministry expected about 22,000 new acres in 2024.

“I think 90 per cent of the new developments were private and 10 per cent out of existing irrigation districts,” Farden said.

Development is spread across the province, including on the western portion of the South Saskatchewan River upstream of Lake Diefenbaker and along the lake itself, both within districts and individually. There is a significant number of acres in development along the Saskatoon South East Water Supply System (SSEWSS), the Moon Lake area and north of Saskatoon around Warman and Osler, Farden said.

There is also new development on the North Saskatchewan River northwest of Saskatoon.

“We’ve seen over the course of the last 15 years now, I guess, about 120,000 acres of development,” Farden said.

The province in 2023 estimated about 75 per cent of the 431,000 irrigated acres are using privately owned and operated development. This differs from Alberta, where virtually all irrigation is done through districts.

Stephanie Boyle and her family are irrigators from Elbow, and she represents private irrigators on the Irrigation Saskatchewan board.

A chartered professional accountant by trade, she worked for MNP in agriculture before being drawn back to the farm.

Irrigation offered her family that chance, she said.

“Irrigation provides tremendous opportunity, so it’s fun to see … to see it from ground zero, to see where it can go,” she said.

That word — opportunity — comes up repeatedly.

She, her parents Lionel and Melody Ector, who were the 2003 Saskatchewan Outstanding Young Farmers, and her brothers Michael and Stuart all use the same wet well infrastructure to irrigate their own farmland. They apply water to about 4,000 acres, or about one-third of the farm, and are working on adding the rest in two phases.

They are the largest private irrigators in Saskatchewan; a few more projects of similar size are in the works.

It’s not a simple or inexpensive process. There are permits, licences and construction to oversee and a lot of learning about the equipment and how to irrigate.

However, Lionel Ector said irrigation is critical and necessary.

“We couldn’t wait on government to put in a large project or make a district that we might be a part of,” he said.

“I’ve been waiting my whole life to have this opportunity to irrigate.”

The family undertook their project in 2023 after three years of drought. The spring of 2024 would be the fifth dry year, but a $6 million investment, including 18 miles of pipe, 18 pivots and all the other required equipment, ensured production.

“Last year we had durum under irrigation. We had some going over 100 (bushels per acre) and the water got onto the land late because that was our first year. On our dry land corners, (yields were) 10 to 15. We had many neighbours that were baling their crops,” Ector said.

Canola went 70 bu. per acre compared to neighbouring yields of about 20.

Ector said it makes sense to grow these crops, even though some say only high-value crops such as potatoes and vegetables should be grown under pivot, because he can double gross income from them.

They also grow pinto beans, black beans, fababeans, and specialty identity preserved canola and durum varieties.

“We were growing seed canola this year,” he said, which can be shipped throughout Western Canada.

“So now we get to keep and develop a value chain at home compared to shipping product off to Chile or Australia and other jurisdictions.

“It opens up a world of opportunity.”

The Ectors and the Boyles did access government funding for their project. Under the current Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership, irrigation developers may be eligible for the lesser of 67 per cent of eligible costs or $1,675 per irrigable acre to a maximum payment of $500,000 over the five-year program.

Eligible costs include pumps, pump stations, turnouts, pipelines, drains, power installation and connection, consulting services and fees for environmental assessment. Funding for power and pipe is eligible up to the centre pivot point of the new acres.

Ector said it’s quite possible other farmers who participate in the cost-shared Westside Irrigation Rehabilitation Project, which is expected to be under construction in 2026, will get more assistance than he did. However, he said as private irrigators, they have flexibility for when they can turn their water on and off, and more irrigation is good for everyone.

“We just want infrastructure, potato plants and other processing, that will improve the viability and economics of our farm going forward,” he said.

If local people don’t take advantage of the opportunity, others will, he said.

Boyle said it’s exciting to be involved in the sector and see the wealth it can generate.

A 2023 analysis showed irrigation increases primary production value in the Lake Diefenbaker Development Area by $832.42 per acre, according to the government.

She said irrigation has allowed them to expand their crop mix and lessen their risk.

“There’s way less reliance on crop insurance,” she said.

“For us to be able to consistently rely on our plans for the crop itself is huge. The banks like it, too.”

She said the boom in private irrigation development is the low hanging fruit as people seek their own opportunity.

In December 2022, the government announced an allocation of 15,000 acres from the SSEWSS canal and that is all private, she said, and there are a number in the Elbow area and along the east and south side of Lake Diefenbaker from the Gardiner Dam to Riverhurst.

Saskatchewan’s growth plan calls for 85,000 new acres by 2030. In the last four years, 58,268 acres were added.

Boyle said irrigation is a long-term investment and landowners have to run their own numbers to be comfortable with their decisions. Future development is likely to be a mix of private and district irrigation.

Farden said the growth has led to considerable demand on government, which provides irrigation certificates. Processing time went up, and the ministry had to cap the amount of field work it was doing itself and rely more on the private sector for services such as mapping and soil sampling.

However, he said the integrity of the process must be maintained.

Boyle said the renewed interest and activity in irrigation from Lake Diefenbaker will help sustain the province economically, environmentally and from a food security perspective.

“It really is a generational shift and it’s exciting to see that it’s happening now and that everybody involved can be a part of it,” she said.