Landowners who want to set up an organized drainage project could learn from one of the province’s newest, the Okabena Conservation and Development Area No.176.

Initiated in 2011 by Moose Jaw River Watershed Stewards, the project covers 14,800 acres that drain from near Rouleau toward Moose Jaw.

Watershed manager Tammy Myers said the organization identified the project to reduce sedimentation and improve water quality entering the Moose Jaw River’s main channel.

She said previous drainage projects had been attempted in the area in the 1960s and 1970s, but landowners couldn’t agree.

Read Also

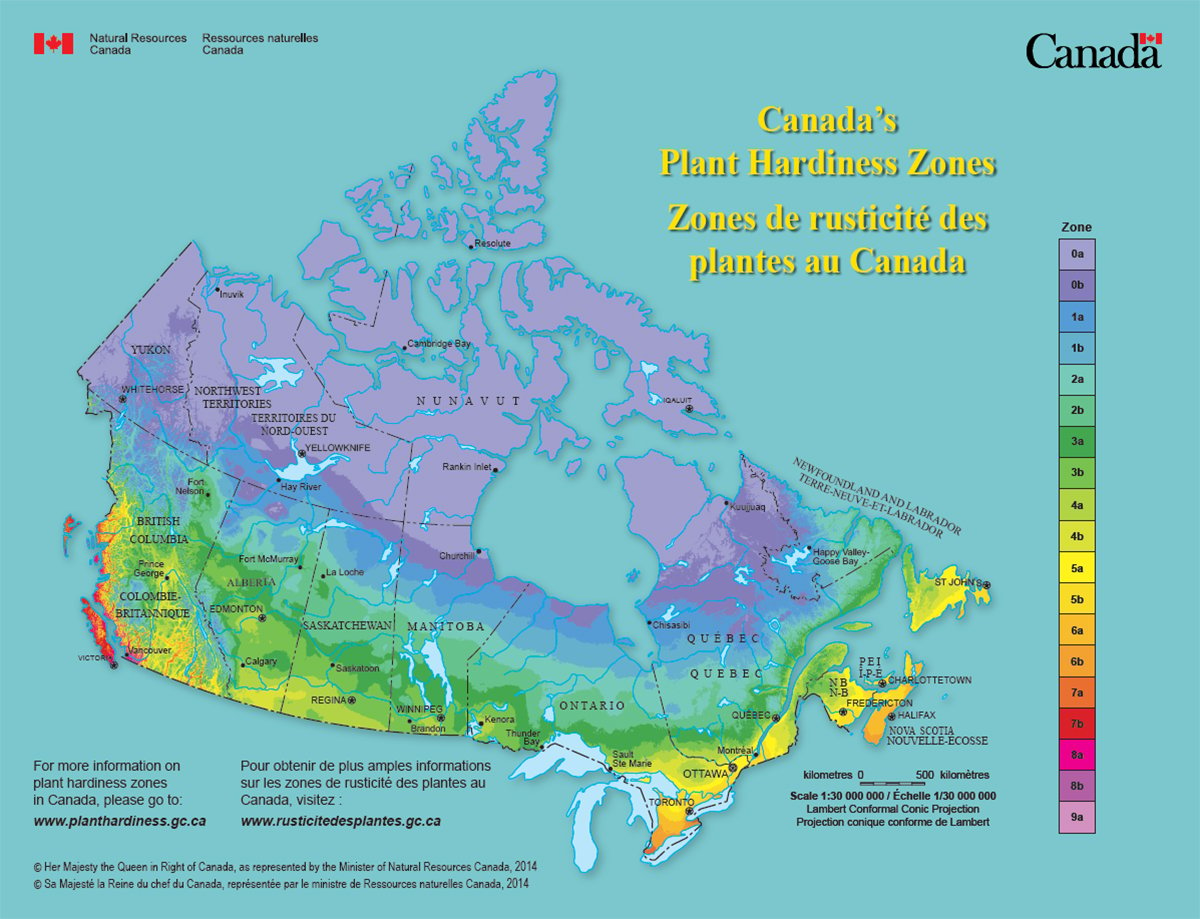

Canada’s plant hardiness zones receive update

The latest update to Canada’s plant hardiness zones and plant hardiness maps was released this summer.

Fourteen landowners got on board in 2011, and it now includes about 50 in two rural municipalities.

“They were open minded and could see the big picture of what this project meant to the environment and to their community,” Myers told a drainage conference.

“It actually took more than six meetings to bring everyone together. Some were upset. A series of meetings need to be held to eventually engage those that need to be in the room.”

Erosion control was the main reason for the project, but it quickly became apparent that forming a conservation and development association would allow for sustainability and producer control and governance of the water basin.

Communication with producers is critical, she added.

Talking to urban municipalities, in this case Moose Jaw, is also important because they will see the benefits of a controlled tributary that won’t contribute to peak flows, she said.

Okabena cost $900,000 and took two years to build. Government contributed $280,000 through a pilot project program, but ongoing costs per acre for maintenance are levied on rural municipal taxes.

Myers said it would help if more technical assistance was available and conservation and development legislation was updated to make it more compatible with how producers operate today.

She said tests within Okabena have already shown a significant reduction in bacteria and nutrients entering the main channel because the water is now travelling more slowly and through a grassed natural waterway.

Conservation and development associations require two-thirds of landowners to sign a petition to form it, and more can be added over time.

“If you contribute water to that basin, you’re in, essentially,” Myers said.