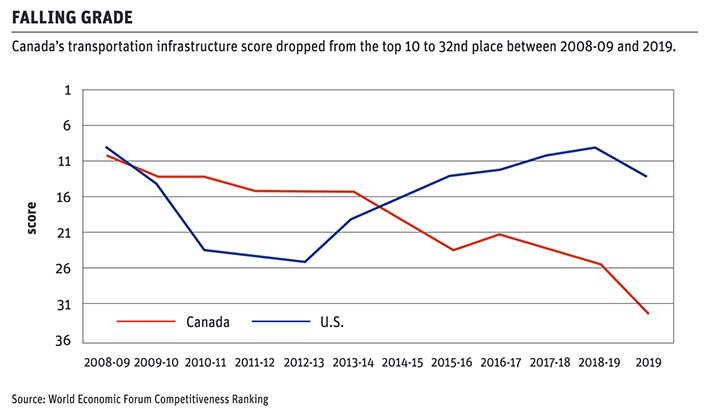

Canada moved from being in the world’s top 10 in 2009 in terms of transportation infrastructure to 32nd place in 2019

CALGARY — Canada needs to get off its “whack-a-mole treadmill” and take national co-ordinated action to reverse a years-long decline in its transportation infrastructure system that producers rely on to reach global markets, says an expert.

“Canada is unique among major exporting countries in not having this … national capacity to understand our system and to make investments based on that knowledge,” said Carlo Dade, director of the Canada West Foundation’s Trade and Investment Centre.

This failure comes at a time when trade with the increasing economic might of the Indo-Pacific region has become one of Canada’s top priorities, he said. About 75 percent of such trade originates in Western Canada, which means farmers are a vital part of the country’s greatest foreign policy and trade challenge, he added.

“We call the Indo-Pacific a generational opportunity, and the generational challenge that requires a generational response. And leading that will be agriculture — leading that will be the Prairies,” he told the recent CrossRoads Crop Conference in Calgary.

Trade accounts for 61 percent of Canada’s gross national product and 34 percent of Alberta’s, or “one out of every $3 in this province,” he said.

It only makes up 23 percent of gross domestic product for the United States and 10 percent for Montana, which borders Alberta. Despite the importance of trade to Canada, the country plummeted from being in the world’s top 10 in 2009 in terms of transportation infrastructure to 32nd place in 2019, said Dade.

The estimate was made by the World Economic Forum as part of its annual competitiveness rankings. It is a global perception survey of confidence in Canada’s trade infrastructure, said Dade.

“This is the perception of users of the trade infrastructure system — so, the assets — the users of rail, road, airports, seaports, the companies that ship, the companies that operate and the companies that rely on them, and the people that work in the industry.”

It is not because of any single occurrence, such as a natural disaster or a strike at a port, but is instead a troubling, decade-long trend, he said. It marks the steady accumulation of “seemingly an endless variety of crises in our trade infrastructure system.”

Dade said the Canada West Foundation spent a decade examining the problem, undertaking a deep dive into organizations such as Infrastructure Australia, which was established in 2008 to provide advice to industry, government and communities about reforms and investments needed to improve infrastructure in that country.

The foundation also looked at Singapore and Malaysia to understand how they managed to raise their rankings compared to Canada, said Dade.

“And the singular thing that sticks out is our inability to understand our integrated supply and production networks: the entire coast-to-coast system for the movement of goods, inputs and products — how what happens in one asset class impacts another asset class and how increase in one area of trade impacts the movement of goods in other sectors.”

A recent report from the European Court of Auditors detailed the differences between how the European Union and jurisdictions such as Canada, Australia, Switzerland and the U.S. planned and delivered infrastructure projects in major passenger transportation and trade corridors. Canada was found to be the only one that doesn’t plan major transportation projects as part of a national long-term strategy, said a slide by Dade as part of his presentation.

“There is little effective co-ordination among the different levels of government, which can lead to second-rate projects being chosen and work being undertaken at cross purposes. Furthermore, Canada has no discernible system for monitoring performance to evaluate projects after implementation and learn for next time.”

Dade said it’s not that Canada has a transportation infrastructure crisis; it’s that it didn’t see the crisis coming.

“Even if you have money, will you be able to invest the money where it’s most needed, or will you continue to instead use as your priority for funding infrastructure something that’s ready to fund, something where there’s a photo op … because that’s the methodology we’ve been using on infrastructure.”

Canadian officials are trusting that somehow each investment is the best use of taxpayer dollars to improve the system, he said.

“No other jurisdiction does that, and they don’t do it for a reason.”

If Canada’s agriculture industry fails to get at the root cause of the problem, producers will “constantly be fighting the same fight in Parliament for special legislation to move grains,” warned Dade.

“You may be successful, but you’re still year in, year out, cycle after cycle going to have to invest. Ladies and gentlemen, we need to get off that whack-a-mole treadmill.”

Canada must also work at its trade relationships “a hell of a lot more than we do now. We can’t expect not to do the work and to not have problems.”

Dade pointed to the challenges of being in a close economic relationship with the U.S., which he described as one of Canada’s most difficult markets despite the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement.

“You’ll see provincial ministers, federal ministers and MLAs constantly in the U.S, and that’s not on vacation, that is doing the work to survive having market access in the U.S.”

Canada isn’t making anywhere near that level of effort in the Indo Pacific, said Dade. It will take a massive investment of human capital and financial resources to build up capacity in markets such as China and India and to build capacity at home, he said.

“Our issue isn’t getting market access. The issue is surviving having market access.”

A particular irony is that Canada and the U.S. are funding organizations such as the Inter-American Development Bank, the African Development Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Bank to help make other trading blocs more competitive, said Dade.

There is only a small development bank in San Antonio, Texas, that funds social projects along the U.S.-Mexican border, he said.

“We don’t invest the money to make North America more competitive.”