Some economists are taking the unconventional position that an agriculture industry that is concentrating into bigger, richer players could be better for producers in some ways

Farmers are shackled to supply chains held by fewer and fewer masters.

Two giant grain companies control half of all grain handled in Canada, with the five biggest firms probably moving more than 75 percent.

A handful of packers process almost all the pigs and cattle.

Two railways move the vast bulk of both crops and meat.

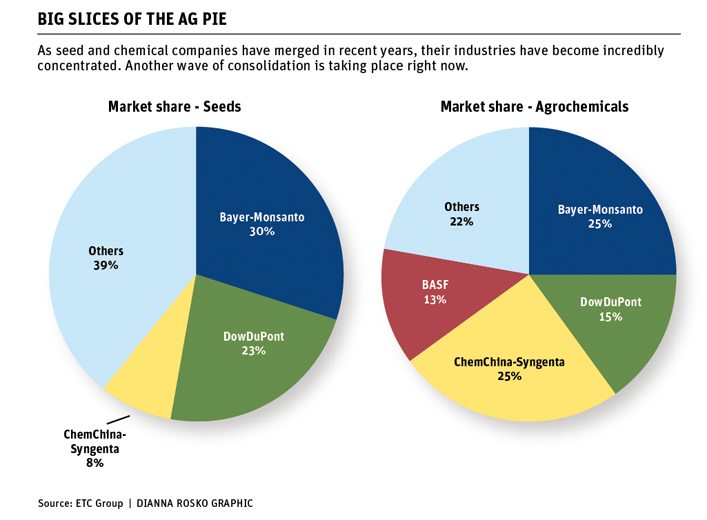

And the world’s so-called Big Six chemical/seed companies are becoming the Big Four as mega-mergers proceed.

It looks frightening for many farmers worried about too much agri-business concentration, which leaves them as price takers who have almost no bargaining power against the corporate giants.

Read Also

Crop quality looks good this year across Prairies

Crop quality looks real good this year, with the exception of durum.

However, the situation might not be as dire as many fear. And while it runs counter to conventional wisdom and common sense, an agriculture industry that is concentrating into bigger, richer players could be better for farmers in some ways.

“It might actually be in society’s best interest to let these firms evolve and concentrate to promote these economies of scale and lower the real cost within the supply chain,” said University of Manitoba agricultural economist Derek Brewin.

“I agree there are some concerns about concentration (but) if there is some feasibility for new entrants … a threat of entry can reduce costs.”

Brewin isn’t a heretic among agricultural economists and analysts. His opinion jibes with many conclusions reached by economists who studied the issue for the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank’s Kansas City office. In September, the Fed published a special report on the issue of concentration and consolidation in agriculture. The evolution of bigger, more intensively capitalized and operated buyers can help the farmers who supply them and isn’t necessarily the problem many assume.

“Farmers can fare very well in modern procurement markets if conditions are right for them to establish a symbiotic relationship with a downstream supplier,” concluded University of California economists Tina Saitone and Richard Sexton in their paper for the Fed discussion.

James MacDonald, chief of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s structure, technology and productivity section of its Economic Research Service, repeatedly noted that “increased concentration does not necessarily imply reduced competition.”

History

Both history and theory have supported farmers’ fear of too-big buyers and suppliers. The 20th century was littered with situations in which North American farmers faced locally dominant buyers and suppliers who could force them to accept prices that seemed extortionate. With thousands of local and small farmers unable to move their crops and livestock far, a local buying or selling monopoly could exert great pricing power.

Farmers might have been individually small and weak, but since they numbered in the millions, they often accrued great political power, and many laws, regulations and agencies were set up to police corporate players.

In 1919, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission blasted what was then the Big Five packers for manipulating the market and hurting farmers and consumers, which led to the 1921 Packers and Stockyards Act.

Other actions in other areas attempted to restrain collusion among dominant companies and exploitation of farmers.

Economists developed complex analyses to describe how concentration affected farmers and society, evolving over the 20th century into a number of streams of theory.

Companies faced pricing, reporting and transparency rules that were designed to ensure farmers had at least some clarity and knowledge about the people buying their products and supplying their goods and services.

Mergers were judged by their possible impact on competition in local markets, with companies often forced to divest assets and operations to avoid over concentration.

Cases of collusion were found and prosecuted, with everything from lysine and pesticide components to (very recently in Canada) bread prices being proven to have been fixed by a handful of dominant sellers.

Governments evolved their own methods of manipulating markets, using monopolies (single sellers) and monopsonies (single buyers) to control prices for farmers or consumers. The Canadian Wheat Board and some countries’ import purchasing boards have been examples.

It’s universally accepted that dominant buyers or sellers of bulk commodities can have pricing power that shouldn’t exist in a competitive market.

Why it now might be different

Farming and agriculture industries have evolved into very different animals to those that existed a few years ago. Bulk production, processing and marketing of commodities is being partially supplanted by specialized and highly refined production; farmers, processors, food companies and marketers want to run with maximum efficiency and little uncertainty; market development depends on a steady flow of product and a minimum of complication.

Rather than the open market providing the best returns, it can become a source of undervaluing of farmers’ products if it can’t provide different values for different qualities of crop or livestock.

“The current reconfiguration of the value chain is going to place an increasing emphasis on product differentiation,” Purdue University economists Michael Langemeier and Michael Boehlje said in a submission for the Fed report.

“Where open markets fail to achieve the needed co-ordination, other options such as contracts, alliances, vertical integration or joint ventures will be used,” they wrote.

“Traditional open markets increasingly encounter difficulties conveying the full message concerning attributes of a product and characteristics of a transaction.”

The North American hog industry has seen a revolution in marketing in the last 15 years, with most pigs now sold under contracts with packers, often with hog genetics, breeding stock and even inputs specified and sometimes supplied by the buyer or its partners. For producing pigs of that nature, farmers tend to receive both a premium over free market sales and much more assurance that they’ll be able to sell the pigs they produce for a price that won’t break them.

That’s where the traditional wisdom about concentration runs into problems. Those concepts don’t necessarily apply well outside of free markets and bulk commodities. Some of these are no longer bulk commodities that have equal value or cost to different buyers or producers.

Especially where research and development is key to the value of the product to the innovator, the farmer, the processor and the consumer, open market economic assumptions run into problems.

One of the main claims for the chemical/seed companies in seeking approval from farmers and regulators for their mega-mergers is that they don’t feel they’re big enough to fund their own research and development ambitions, since those now sprawl across multiple levels.

“The combined business will be ideally suited to cater to the requirements of farmers … because we have equal and meaningful strength in crop protection, seeds and traits and digital and analytical tools,” said Bayer chief executive officer Werner Baumann at the 2016 announcement of his company’s agreement to buy Monsanto for US$66 billion.

Similar arguments were made with the Dow-DuPont and ChemChina-Syngenta deals. Crop packages, now and in the future, will go far beyond a one-product focus and instead be stacked with features.

It might be hard to imagine the life-science giants feeling cash-strapped, but with some estimates putting the cost of a new pesticide at about $300 million and a new biotech commercial crop trait at around $200 million, and much research coming to naught, the claim might not be that far-fetched, some economists feel.

The increased cost of new facilities in the transportation, grains and meat industries is not as hair-raisingly risky as investing in biotechnology innovations, but they are still hard for small or medium-sized players to carry. Only giants can take on some giant-sized tasks.

New high-tech slaughter and processing plants aren’t cheap. Neither are port terminals or increased track capacity.

The same phenomenon has been playing out among farmers too. Bigger and more technologically developed farms tend to have lower costs of production, and in cyclical periods of low-margins, that can be the difference between survival and failure. As smaller farms fail, the bigger farms get bigger and bigger, and have more and more ability to supply the differentiated products that big buyers want.

Concerns

That doesn’t mean the widespread concerns among farmers and consumers about the impact of increasing concentration and mega-mergers isn’t justified.

Many note that government competition regulators tend to take narrow focuses and do not look much at wider social impacts of corporate consolidation.

While many economists are willing now to accept that a more concentrated market isn’t necessarily worse for farmers and consumers, they aren’t willing to assume there’s nothing to worry about.

“We need to monitor these sectors,” said Brewin.

“We need data on whether the costs are really falling and whether any of the gain is being shared with the rest of the supply chain.”

MacDonald said that while there are good arguments that a company’s ability to innovate could be improved by merging with a complementary company, it won’t necessarily provide an incentive to invest in innovation. If new products simply kill sales of its old products, there isn’t much incentive to spend on innovation.

On the other hand, it might provide a strong incentive, even if it is a giant that controls its market, if it fears competitors might enter into its market.

“A large firm with a dominant market share may still have incentives to invest in innovation if it fears a rival may scoop it with a major new innovation,” said MacDonald.

The reality is that each situation is different and simple assumptions are of little use. Assumptions that corporate concentration is bad for agriculture need evidence, such as data on rising input prices outpacing gains in sales for users like farmers, that innovation is being stifled, or that the concentration prevents other companies from entering the industry.

That’s where Jennifer Clapp of the University of Waterloo’s School of Environment, Resources and Sustainability calls for caution. Far too many impacts and issues have not been adequately studied, she said.

“Past episodes of consolidation in the sector had important implications for questions of economic fairness, farmer autonomy, environmental sustainability and political power, and … the proposed mergers (of the life science companies) are likely to result in even more pronounced effects on these fronts,” she wrote in her analysis Bigger is Not Always Better: Drivers and Implications of the Recent Agribusiness Megamergers.

“Yet while these concerns are wide-ranging, the evaluation measures used by regulatory bodies to assess the impacts of the mergers only partially capture the ways in which they affect economic fairness, and say little on questions of environmental impact, farmer autonomy and power inequities.”

That is the clearest conclusion about the impact of corporate concentration on today’s farm economy: much has changed, and too little study is being done.

There isn’t necessarily a problem, but there might be and it is hard to know without more work from agricultural economists as their profession and farmers’ reality evolves in the shadow of mega-mergers and hyper-concentration.