Since about 1980, temperature data shows that the world is getting warmer. And the last two decades have been particularly hot.

“Nineteen of the hottest years (on record) have occurred since 2000,” NASA says on its climate website.

Such temperature data can be found on thousands of websites, from hundreds of organizations.

But it’s harder to find data on wind and how climate change is affecting wind speed.

David Phillips, senior climatologist with Environment and Climate Change Canada, said wind speed is one of the least-studied aspects of weather.

“It’s not that it’s not important. It’s really important,” said Phillips, who has worked at Environment Canada for more than 40 years.

Wind is important and can be extremely destructive. Hurricanes, tornadoes, derechos (plow winds) and other storms cause billions of dollars in damage every year in North America. On farms, high winds are a threat to structures like grain bins and machine shops.

On Aug. 10, 2020, a series of storms with high, straight-line winds (known as a derechos) caused an estimated US$11 billion in damage across the Midwest.

“In Cedar Rapids (Iowa), winds reached as high as 140 mph… equivalent to a Category 3 or 4 hurricane,” National Public Radio reported.

One school of thought is that climate change is causing more storms and making storms more powerful. But that runs counter to what scientists know about climate change.

The Arctic is warming faster than other parts of the globe. So, there should be a smaller difference in temperatures between the Arctic and southern Canada in the future.

“As we continue to warm up, the temperature differentials between the north and the south are going to be less,” Phillips said.

“One of the drivers of wind… is temperature difference. If the temperature difference (between the north and other parts of North America) becomes less, one might expect winds to lessen.”

Recently, Phillips looked at data from eight weather stations across southern Canada to see if it’s getting windier. He studied the information to prepare for an urban forestry conference this fall in Charlottetown where he’s making a speech. He tracked the number of days per year at airport weather stations where the wind or gusts exceeded 40 km-h.

It turns out that the number of days with strong winds is increasing.

“In the last 10 or 15 years, there’s been about a 15 percent increase in the incidence (of windy days),” Phillips said, adding his research was not rigorous, as he only looked at eight stations across Canada.

Still, there is some evidence that windstorms and tornadoes are happening more often. And in geographies where tornadoes are rare.

The Northern Tornadoes Project, a Western University initiative, has been collecting data on Canadian tornadoes for years.

In its 2021 annual report, project leaders said there were “tornadoes in… both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts for the first time in decades… (and) a record number of significant tornadoes in Ontario.”

Such data on tornadoes, showing they’ve become more frequent and widespread, could be deceptive.

Thirty years ago, few people had a cellphone and almost no one was a storm chaser. So, in July of 1992, it’s possible that a tornado touched down near Killarney, Man., but no one was there to record it on their cellphone.

“Now, everybody and their brother is taking pictures of it,” Phillips said. “The way we observe them now is totally different…. We used to say, we would get 60-80 tornadoes a year in Canada. But we think we (actually) got two or three times that (amount). But nobody was around to see these things.”

Phillips may be correct.

Groups like the Northern Tornadoes Project are recording more tornado sightings in Canada because they’re looking for tornadoes with drones, radar and other equipment.

“The 2019 season was NTP (Northern Tornadoes Project) first full investigative effort,” the Weather Network reported. “NTP found 89 tornadoes that otherwise would not have been identified, increasing the national tornado count in 2019 by 78 percent.”

Still, it’s possible that tornadoes are becoming more severe and that windstorms will become more extreme in Canada, because of climate change. There’s also the risk that such storms will happen in locations that are outside the usual tornado zone of the southern Prairies.

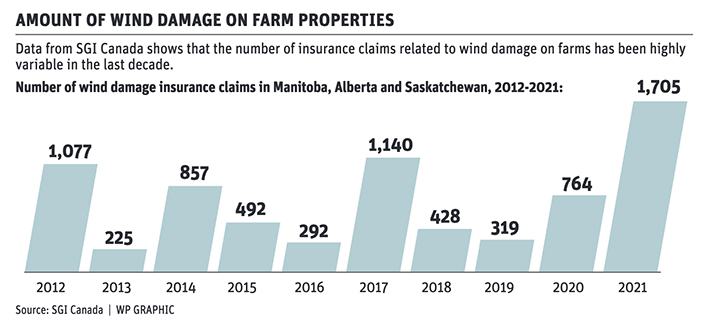

“Pushing up that temperature increases the geography these storms may impact,” said Andrew Voroney, regional vice-president for Saskatchewan with SGI Canada, an insurance firm, in SaskBroker Magazine.

“All of a sudden, Prince Albert is at-risk of a large tornado that, 10 or 15 years ago, we wouldn’t even have worried about. Temperature increases widen the actual area that could get damaged.”