REGINA — Prices for grains and oilseeds have significant support for the near future, and with input prices where they are, that is a good thing.

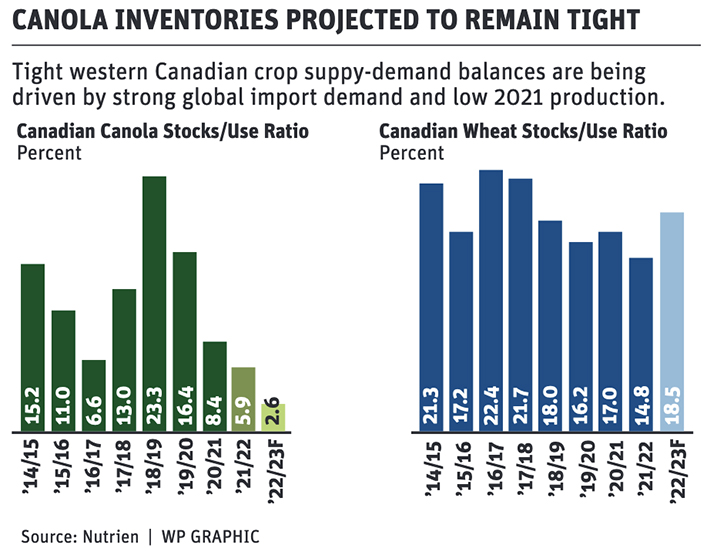

World stocks-to-use ratios for grains are at a 26-year low.

“Not since 1996-97 have we seen numbers this low,” said Jason Newton, the chief economist for Nutrien and head of market research for the company. Newton was speaking to a crowd of about 300 people at Grain Expo, held in conjunction with the Nov. 28 to Dec. 3 Canadian Western Agribition in Regina.

Newton said the tight supplies aren’t likely to loosen in the near future, “however we get a new (crop) cycle annually, so we can expect a rebound at some point.”

He pointed to an American winter wheat crop that started the season in a poor situation and is getting worse.

While no one can write off American winter wheat crops this early in the season, the trade doesn’t appear to be supporting strong yields for next summer’s harvest in that region.

Tyler Freeman of Parrish and Heimbecker agreed that strong prices will likely continue into the immediate future with western Canadian spring wheat priced above $11 and canola in the $15 to $20 range — acknowledging that was a very wide range due to too many issues at play in the trade.

The volatility in the grain market is due to a variety of factors affecting more than just yields. Both speakers said that, while nothing is certain, the trend appears to support lower supplies of grain for this year.

And both suggested the long-term trend toward larger per-acre crop yields will also continue.

Newton said by 2018, Russia and Ukraine had become the suppliers of about half of the global wheat trade, so the war and the accompanying sanctions and shipping issues are having dramatic effects on the market. Those two countries will plateau in production “at best” for this coming crop, despite Russia having a very strong harvest. Added to that Australia and Argentina will likely be delivering shorter crops than normal.

He pointed to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s reported food price spikes during the past 50 years and the resulting effects on land use and yields after these were recorded.

Grain acres typically shoot up after periods of extreme food inflation. In the 1970s, grain area rose to more than 120 million acres at one point, based on rolling five-year averages. After the food inflation spike that followed the American drought a decade ago, combined with the increased biofuel use and mandate that diverted huge amounts of corn from food to fuel, acres again rose strongly. That came after about 20 years of falling grain acres.

Typically, the demand for grains results in sustained higher prices for a period long enough to incentivize producers to use every tool they have to grow more. That generally results in making choices about farmland use, including breaking up permanent forages.

“That isn’t a great carbon choice and we hope (the industry) focuses on yield (improvement) instead,” he said.

Freeman said the incentives exist to grow more bushels and should continue to drive producer decisions to heavily invest in their crops and that will support the trend of rising yields in coming years.

“Despite higher farm costs and inputs prices, the margins are there to support this,” he said.