The number of shipping containers leaving Canada without goods drops from its peak, but the percentage remains high

Like the pandemic, everybody wants to see the container shipping crisis just fade away into memory.

Unfortunately, it’s taking a long time to fade.

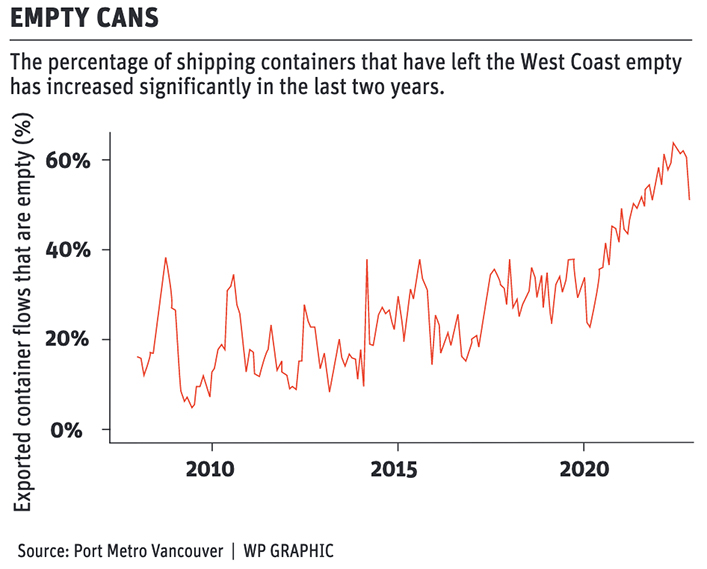

“In November 2022 the share of outbound empties fell to 51 percent, the lowest it has been since August 2021’s 50 percent,” noted analyst Chris Ferris of Economic Development Winnipeg in late 2022.

“It is perhaps too early to tell, but we could be seeing the share of outbound empties beginning to normalize.”

That’s likely the hope of most farmers and Canadian crop exporters after a two-year nightmare of seeing about two-thirds of the containers leaving the port of Vancouver empty, even though Canadian pulses and other specialized grain shipments were backed up on farms, in elevators and at port facilities, unable to get onto Asia-bound ships.

Canadian-owned and loaded containers were often ignored in the clamour from Asian exporters to get their containers back across the Pacific Ocean as fast as possible.

“Many of the shipping lines decided that they needed the empty containers back in the Asia-Pacific countries a lot more than they needed any kind of revenue from bulk products that are being shipped out of Canada,” said Mark Hemmes, president of federal grain monitoring firm Quorum Corp., during the Fields on Wheels conference in December.

“Therefore, they demanded that no product be loaded in Canadian containers and to expedite the movement of empty containers back to Japan, Korea, China (and) Indonesia.”

At times almost all containers were leaving Canada empty.

The recent sharp break from plus-60 percent empties to just above 50 percent is a promising cracking in a trend that goes back to the beginning of 2020, but only gets halfway to the 40 percent empties rate that prevailed pre-pandemic.

Since 2000 the rate has averaged around 20 percent, but it moved higher from 2015 and then spiked in 2020.

Demand for manufactured products surged during the pandemic as hundreds of millions of consumers were forced to stay home due to lockdown restrictions, governments gave them money to partially make up for lost wages and many turned to goods purchases to make up for the travel, entertainment and dining they usually spent their disposable money on.

At the same time, factories and supply chains faced repeated shutdowns and delays due to COVID, reducing the supply of commodities, transportation and manufactured goods. Prices surged as consumers in places like North America demanded goods from production-impaired regions such as eastern Asia. Asian exporters were willing to pay much more to bring an empty container back to Asia to refill with manufactured products than a grain exporter could afford to pay to ship a crop-filled container to Asia.

Many hoped the shipping situation would normalize before long.

A long-term strategic goal of the Canadian export agriculture industry has been to find more buyers for Canadian products, rather than relying so heavily upon a few markets like China and Japan. Other markets could have a better balance of supply and demand for exports and imports.

But who?

Barry Prentice of the University of Manitoba’s Transport Institute said there are signs that other markets are being developed.

“The mere fact that we’re doing more trade with Bangladesh and Vietnam means that we’re going to have more containers going back,” said Prentice.

“In the degree that we see diversification of these markets, it actually is a very good thing.”

Keystone Agricultural Producers president Bill Campbell was cautious about the hopes for building new markets to substitute for old markets.

“It takes time to build a credible relationship with new customers. How can we ensure that we can deliver (what they demand,) but as well we need to ensure that that same responsibility is reciprocated,” said Campbell.

This is especially true if trade is disrupted by disputes or technical snarls.

“It certainly places a huge impact on that primary producer.”

Hemmes said the apparently improving situation with empty containers is a positive development, but more improvement is needed.

“I think it’s still going to be a while before the entire container industry through North America has found itself back into a balanced cycle of containers,” said Hemmes.