SASKATOON — Bob Larocque had one takeaway from his presentation at Canola Week 2023.

“Remember carbon intensity because that’s the game changer,” said the president of the Canadian Fuels Association.

It is a factor that will help determine the value of canola when large volumes of the crop are being consumed by the renewable diesel sector.

His member companies account for 95 percent of Canada’s production of transportation fuels.

The annual demand for biofuel in Canada is expected to reach 10 billion litres by 2030. That includes 3.5 billion litres of renewable diesel, a seven-fold increase over 2022 levels.

Read Also

Canola oil transloading facility opens

DP World just opened its new canola oil transload facility at the Port of Vancouver. It can ship one million tonnes of the commodity per year.

Manufacturers will be using a variety of feedstocks to produce that fuel and what they choose will be heavily influenced by the carbon intensity scores of those feedstocks.

“For us, that is very important, and we monetize that big time,” said Larocque.

Chris Vervaet, executive director of the Canadian Oilseed Processors Association, said the canola industry needs to roll up its sleeves and improve its score.

“We’ve got some work to do in terms of reducing our emissions,” he said.

Canola’s carbon intensity score is worse than competing feedstocks like soybean, animal fat and used cooking oil (UCO). That is primarily because the crop requires heavy doses of nitrogen fertilizer, which offsets its carbon sequestration benefits.

The other factor keeping canola’s score elevated is the lack of productivity gains. Average yields have been stuck around 40 bushels per acre for the past decade.

“Output is a big part of this carbon intensity equation,” said Vervaet. “We need more canola.”

Carbon intensity scores have a substantial impact on the bottom line for renewable diesel manufacturers because they collect credits amounting to about $100 for every tonne of carbon dioxide reduction.

A renewable diesel plant that produces one billion litres of the fuel per year could earn $248 million in credits for using UCO as its feedstock versus $146 million for canola.

“You bet they’re going to be looking for as much UCO as they can get their hands on,” said Vervaet.

But canola is still expected to be the feedstock of choice for Canada’s plants and will also be in high demand in the United States.

COPA is forecasting 6.8 million tonnes of demand from North America’s renewable fuels sector by 2030, up from 2.4 million tonnes in 2022.

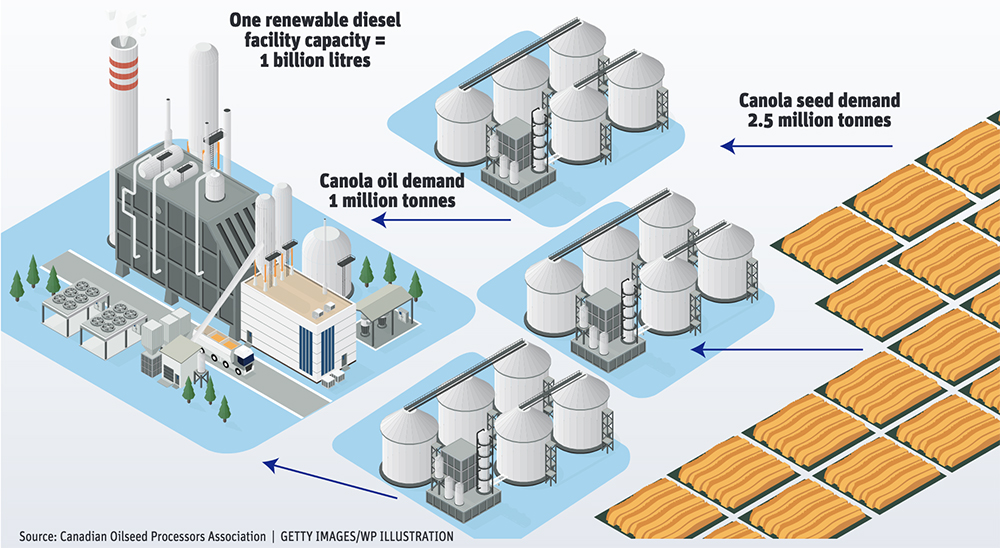

Larocque indicated the volumes could be much higher. He said Imperial Oil’s one billion litre plant planned for Strathcona County in Alberta could consume 2.5 million tonnes of canola annually if that was the only feedstock it used.

That is more than what Canada typically exports to Japan in a given year.

“That’s just one (plant) and there’s probably going to be five to seven more of those by the end of the decade.”

Vervaet said there will still be plenty of canola for the food and feed markets. He is forecasting 29 million tonnes of production by 2030, up from 20 million tonnes in 2022. Three-quarters of that production will go to traditional food and feed markets.

Larocque was asked about the backup plan if canola can’t deliver quantities that the renewable diesel industry requires.

Canada has 25 million tonnes of forest residue that could be used as a feedstock and the provinces support that idea to prevent forest fires. However, the industry is three to four years behind agriculture in developing the feedstock. Wood is harder to liquify than crops.

And there is another big obstacle to overcome.

“The problem is the supply chain that you have in agriculture is five to 10 times more efficient than it is with the forest residue right now,” said Larocque.

The upshot is that if the canola industry can’t deliver, fuel manufacturers would have to inform Ottawa that they won’t be able to abide by Canada’s Clean Fuel Regulations.

“So, we are absolutely counting on you,” he told Vervaet. “Build those crush plants.”

Canada now has 14 canola crush plants with 11.2 million tonnes of capacity. Five new projects have been announced that would boost capacity to 18 million tonnes over the next five years.

Total crush in 2022 amounted to 8.7 million tonnes or 45 percent of the 19.5 million tonnes of canola produced that year.

COPA is forecasting 16.2 million tonnes of crush by 2025, which would be 70 percent of the estimated 23 million tonnes of production by that time.

Those plants will supply canola oil to what is eventually expected to be seven renewable diesel facilities operating in Canada, producing four billion litres of fuel per year.

There will be another 25 plants in the U.S. with 28 billion litres of capacity.

Larocque warned that the Canadian plants might not be built if the federal government doesn’t make some type of response to the tax credits contained in the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act.

Those credits are only available to U.S. manufacturers, who will collect them and then export their product to Canada, where it will then receive more federal and provincial credits. The U.S. credits amount to between 10 and 60 cents per litre.

Larocque was hoping the Canadian government would signal in its Fall Economic Statement that a policy response was coming in Budget 2024.

“Unfortunately, there was nothing,” said Larocque.

He said his association will continue to lobby federal finance minister Chrystia Freeland and energy minister Jonathan Wilkinson to get something in Budget 2024.