Palmer amaranth hasn’t been found in Saskatchewan — yet.

But with a recent finding in Manitoba and an established presence in North Dakota, research scientist Shaun Sharpe says everyone should be on the lookout.

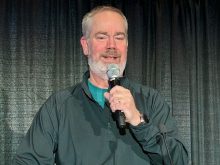

“I’m very, very concerned about this weed,” said the Agriculture Canada weed researcher based in Saskatoon.

“It’s incredibly invasive. It causes catastrophic yield losses in corn and soybeans.”

Sharpe said anyone who spots a “weird-looking pigweed” should take note. Palmer amaranth and waterhemp are both invasive pigweeds that are moving closer thanks to birds, animals and humans.

Read Also

Short rapeseed crop may put China in a bind

Industry thinks China’s rapeseed crop is way smaller than the official government estimate. The country’s canola imports will also be down, so there will be a lot of unmet demand.

“They’re very much dispersed by us, and that’s largely how it’s moving around,” he said.

Identifying Palmer amaranth is crucial, he said.

“Look for smooth stems. This will tell you if it’s Palmer or waterhemp. And the way to tell them apart is going to be the long petiole on the leaf,” he said.

“If the leaf petiole is as long as the leaf you’ve probably got Palmer.”

Indigenous cultures in the American southwest grew amaranth for food security. Some grew it with their corn and hoped for a yield of one or both.

But over time the strength of one particular type, Palmer, began to take over.

As early as 1955, an American botanist reported that the population had exploded. Sharpe noted this was well before the broad use of herbicides.

Much of the spread occurred in artificial habitats such as ditches and irrigation canals.

Over time Palmer amaranth showed a remarkable resistance to herbicides.

Sharpe showed a photograph from Tennessee, where a dicamba-tolerant soybean crop had been overtaken by Palmer amaranth.

In Kansas, a corn field suffered 91 percent yield loss, while the loss in soybeans was 79 percent.

“These are herbicide tolerant crops, systems, heavy hitters, and this weed is breaking through at an alarming rate,” Sharpe told a SaskCanola meeting.

Several modes of action have been lost in the United States with six-way resistance reported in 2021.

Sharpe said it’s just a matter of time before Saskatchewan is dealing with it. A study of ducks’ stomach contents, obtained from hunters in Illinois, found both Palmer amaranth and waterhemp.

“Our concern currently is that they’re moving through the corn belt on their way north, in migration, and the corn belt is where all the Palmer amaranth is, so if they’re looking for grains on the ground, it produces so much grain and it is quite edible,” he said.

The weed is resistant to both Group 2 and Group 9 herbicides in North Dakota. Studies have also found PPO-resistant (Group 14) waterhemp in the state.

“As we’re trying to manage kochia and we’re using Group 14s, if you see any weird pig weeds please tell somebody, anybody, because we don’t want them establishing,” he said.

Minnesota has done a good job of studying the weed’s pathways and controlling it.

It has been found at grain millers, in screenings for animal feed and, in North Dakota, a contaminated combine.

Sharpe said eradication is possible if a jurisdiction has a good framework to deal with it.

Right now awareness is key in Saskatchewan.

“We need everybody to be on the same page and to be aware that it can come here and it probably will,” he said.

“I’m anticipating maybe five, 10 years we’ll be seeing its introduction.”