MINNEAPOLIS, Minn. — Grain was moved only in bulk when Stephen Lofberg started in the grain shipping business more than 40 years ago.

A portion of the business shifted to containers over the last 10 years because it was a cheaper way to get grain to overseas markets.

“There was no way that the bulk business was competitive with the container business into the Asian market,” Lofberg, an international shipping, trade and logistics expert, told delegates attending the recent Oilseed & Grain Trade Summit.

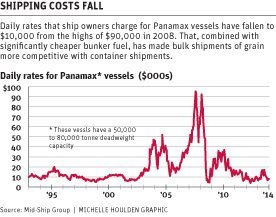

However, the pendulum has swung back in a big way because of reduced ship rental and fuel costs.

Read Also

Defence investments could benefit agriculture

A bump in Canada’s NATO spending commitments could lead to infrastructure investments that would benefit rural areas

“I feel sorry for the container guys because bulk is back,” he said.

Containerized waterborne ex-ports of U.S. grain through the first half of this year were 3.39 million tonnes down from 4.44 million for the same period a year ago and the three-year average of 4.3 million tonnes.

Ken Ericksen, senior vice-president with Informa Economics, said the United States typically moves three percent of its grain by container.

“Right now, coming into harvest, it’s not even one percent. We’ve really fallen off from the spring,” he said.

That is because Panamax ships that cost $90,000 per day in 2008 are now renting for $10,000 per day because of an oversupply.

Shipbuilders expanded the fleet in anticipation of continued strong economic growth in China. That optimistic demand outlook, when combined with rock bottom financing costs, resulted in a shipbuilding explosion.

However, the Chinese economy has cooled, and the days of double digit growth are over. The Chinese government says the economy grew at a rate of seven percent in the second quarter of 2015, but many analysts think the real number is closer to five percent.

“All the assumptions about China from five or six years ago are done. Forget it. They’re done,” said Lofberg, president of Mid-Ship Group.

The slowdown in the Chinese economy is happening at a time when a lot of new ships are being launched, which has forced ship owners to cut their per diem rates by as much as 80 percent from the highs of seven years ago.

Fuel costs have had an even more dramatic impact on bulk grain movement. Bunker fuel that sold for $600 per tonne a couple of years ago has dropped to $200.

That is a massive savings, considering a ship burns 30 tonnes of fuel a day in a typical 45 day trip from the United States to the Far East — a $540,000 reduction in fuel costs for that voyage.

Lower shipping costs have a bigger impact on bulk than containerized shipments because bulk is a true supply and demand based industry, while containers are a back-haul business designed to reduce the $500 to $600 cost of shipping an empty container back to Asia.

Lofberg said farmers should watch what is happening with shipping costs because it has a big impact on their bottom line.

A recent study published by the American Farm Bureau detailed the cost of shipping corn from Minneapolis to Japan through the U.S. Pacific Northwest.

The farmer received $3.54 per bushel for corn that had a landed value of $5.89 in Japan. That is due to truck freight costs of 30 cents per bu., rail freight of $1.43 per bu. and ocean freight of 62 cents per bu.

Eriksen said this year’s grain export program is off to a slow start.

“We’re listening every day to railways and barge operators asking, ‘well, where’s the grain? We’ve got equipment. We’re waiting. We’re not seeing it coming,’ ” he said.

Railways are moving less coal and crude oil and are eager to transport grain. Barge operators and transloaders are also champing at the bit.

“One year ago, transloaders wouldn’t even return phone calls, shippers were telling me. This year they can’t beat the transloaders off,” said Eriksen.

The strong U.S. dollar is making American grains and oilseeds less competitive in overseas markets. Farmers are waiting for prices to rise, and buyers are waiting for them to fall.

Eriksen said the stalemate is problematic because October to December is the peak shipping time for U.S. grain.

“You’re running close to half of your annual U.S. grain export program in three months and then you get to January and February and it starts to fall off like an avalanche,” he said.

Prices will eventually reach a level that is conducive to grain movement, and then watch out.

“Every transloader is going to be lit up like a Christmas tree,” said Eriksen.