Glacier FarmMedia – Could a more dangerous world inadvertently drive investments that benefit Canada’s agriculture sector?

Some analysts think so, but it’s uncertain what infrastructure investments will be considered “defence-adjacent,” such as airports, ports, telecommunications, emergency preparedness systems and other dual-use investments that serve defence as well as civilian readiness.

This past June, member states of NATO formally pledged to increase defence spending from two per cent to five per cent of gross domestic product. For Canada, a founding member of the alliance, that means investing some $150 billion annually.

Read Also

Manitoba community projects get support from HyLife

HyLife Fun Days 2025 donated $35,000 each to recreation and housing projects in Killarney, Steinach and Neepawa earlier this fall.

The bulk of that money, three to five per cent, will go toward military hardware, personnel and other materiel required for the defence of Canada and its allies. The remaining 1.5 per cent, however, is earmarked for a wider suite of defence-adjacent initiatives, such as improvements to critical national infrastructure, innovation processes and communications.

Though quite general, some of the defence priorities identified by prime minister Mark Carney reflect similar requests stemming from many in Canada’s agriculture sector.

This includes a large coalition of agriculture groups that penned a letter to the prime minister earlier this summer, asking his government to “prioritize transportation and trade infrastructure that support agriculture — including rail, port and cold chain infrastructure as well as rural infrastructure needed to reach national corridors, while at the same time ensuring the reliability of service needed to maintain Canada’s reputation as a reliable supplier of agriculture products.”

Whether infrastructure investments go to projects in regions where farmers and agribusinesses can make use of them is not guaranteed.

Ugurhan Berkok, associate professor at the Royal Military College of Canada and an economist specializing in the defence sector, says intelligence capacity and capability will be particularly important as Canada, being an Arctic nation and critical intelligence ally of the United States, seeks to improve capability in the North.

Modernizing the North American Aerospace Defense Command, for example, will require additional manpower, investments in facilities and roads and other infrastructure to keep facilities in operation. Such infrastructure will likely have little to no effect on the agriculture sector, given how far north they are.

But similar investments in east-west infrastructure might be a different story.

Fertilizer, food and telecommunications

Al Mussel, agricultural economist, research lead for the Canadian Agri-Food Policy Institute and founder of Agri-Food Economic Systems, agrees that investments in Arctic infrastructure will likely have “minimal implications for agriculture.”

If, however, the government’s strategy involves developing the Port of Churchill or another salt-water port on Hudson Bay, agricultural commodities, such as grain and fertilizer, would benefit from another export location — and one more conveniently located for the delivery of critical food and mineral products to many allies and trading partners.

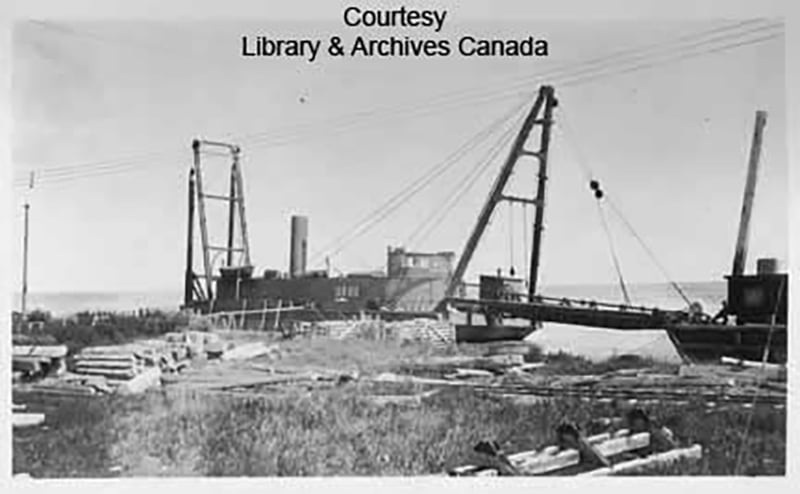

This very thing was attempted in Nelson, Man., during the First World War, although the project was abandoned in 1917.

One of the challenges with developing ports at Churchill, and elsewhere in the wider region, is overcoming transportation issues across northern muskeg and longer periods of thaw. Mussel says transport issues are what have scuttled development plans in the past.

As reported by Glacier FarmMedia in March 2024, the port’s recent history “has been messy, with the sole rail line linking Churchill with the rest of the province plagued by service disruptions.”

In 2018, the port’s American owner, Omnitrax, sold it and rail line because it could not manage the cost of rail repairs. Better environmental conditions, lower insurance cost and a higher car cycle also make southern ports more attractive for grain companies.

There is still some interest in a northern port, however, with the premiers of Saskatchewan and Manitoba signing a memorandum this July to improve access to Churchill for the purposes of exporting prairie commodities.

Port difficulties aside, Mussel believes the strategic value of food and fertilizer export capacity should not be underrated. He cites both world wars, when the United Kingdom was sustained largely by Canadian and American food exports, as historical lessons that appear to be “conveniently forgotten” today.

A similar point is made for fertilizer and mineral resources. During the First World War , the British Empire and its allies had access to fertilizer-rich regions of the world, enabling the production of both food and explosive munitions.

Germany, on the other hand, had to rely on the production of synthetic fertilizer through the Haber-Bosch process. This proved to be a debilitating problem for the Central Powers as the war went on because fertilizer production was increasingly diverted to the development of munitions, including explosives and poison gas.

While Canada is a global supplier of potash, Mussel says it’s possible other vulnerabilities could be addressed if mineral exploitation is considered defence-adjacent spending. To that end, Ontario and other provincial governments have identified mining projects as top economic priorities.

“We know in terms of making monoammonium phosphate, diammonium phosphate or triple superphosphate, there’s nothing in Canada. It’s a major source of vulnerability for us,” says Mussel, citing ongoing pushes for mining in Ontario’s Ring of Fire, a region with promising mineral development opportunities, which could secure domestic supplies of fertilizer as well as some of the materials required for semiconductors and other important products.

Chris Sands, director of the Hopkins Center for Canadian Studies at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, points to the strategic value of combining Arctic port expansion with mineral extraction.

In a Substack article published just prior to NATO members announcing their new spending commitment, Sands argued that “ports on Hudson Bay and the Arctic islands offer access to the North and world markets. Churchill, Man., hosts a deepwater port, an airport and a rail line to the south, and all need new investment. A new port close to Ontario’s critical-mineral rich Ring of Fire region could be a more practical route for bringing minerals to world markets than road or rail.”

Both Berkok and Mussel point to a long-standing issue across rural Canada — access to high-speed broadband — as another area where infrastructure investments for strategic purposes could bring clear dual-use benefits.

From a military perspective, Berkok says artificial intelligence and developments in advanced monitoring systems at military installations — systems built to rapidly “compute signals from beyond the horizon” — will require large servers with significant energy requirements.

Broadband communications more generally will continue to be a critical and growing requirement wherever the government decides to invest in defence installations.

Civilians living in areas long neglected by telecommunications providers, including the far north and rural parts of the country, might inadvertently find it easier to access broadband services as providers prioritize specific networks.

Canada’s powerhouse

The $150 billion invested into defence annually is no small number. Coincidentally, it’s also the amount agriculture contributes to the Canadian economy every year.

For Keith Currie, president of the Canadian Federation of Agriculture, the new NATO targets offer another opportunity to leverage agriculture for economic security against threats from maligned actors.

Historically, however, there has been a lack of recognition of how much agriculture contributes to the country’s gross domestic product — approximately seven per cent — and the potential to grow that revenue through strategic investments from the federal government.

Forestry, steel and aluminum manufacturing and the automotive sector garner a lot of attention, Currie says, yet combined do not contribute as much to the national purse nor employ nearly as many people as agriculture.

He encourages policymakers to dust off the Barton Report, a comprehensive set of recommendations for economic investment from the federal government’s Advisory Council on Economic Growth released in 2017, which identified the agriculture and agri-food sector as a strategic area with “a strong endowment and untapped and significant growth potential.”

Currie lists several gains, including resolving general structural dysfunction at the Port of Vancouver, enabling a method of access to port infrastructure at Prince Rupert, improving storage capacity in Thunder Bay and Churchill, investing in electrical and natural gas infrastructure in farming communities and expanding rural broadband access.

“Infrastructure like hydro lines are 90 years old. Farms are requiring much more power now, but most farms don’t have three-phase power,” Currie says.

“Agriculture is the number one industry to be investing in in this country, and that hasn’t changed. There can be a lot done without a lot of money or in combination with different programs.”