I recently dealt with a bovine case of swelling under the jaw, and it wasn’t what I expected.

As a result, I would like to go through several things to look for when dealing with cases like this.

Don’t assume anything. Look closely for clues and remember that treatment may be different in each case.

Read Also

Quebec pork company calls for transparency around gene-edited pigs

Quebec-based pork company duBreton is calling for transparency around meats from gene-edited pigs on concerns that a lack of mandatory labelling will confuse consumers, and dilute certification claims. The organic sector is also calling for labelling rules.

Swelling under the jaw is usually very visible to livestock producers. It is not a common clinical sign, and most times it is limited to a single animal, except for one condition.

Cattle that become very thin from sickness, diarrhea or poor quality feed or starvation get hypoproteinemic. This condition allows fluid to leach out either internally on the belly around the umbilicus or the area under the jaw, which is called a submandibular edema.

This may affect more than one animal, especially if it is caused by feed quality or quantity issues.

The condition can affect not only the health of the fetus but could also impede the cow’s ability to cycle and rebreed. These problems can have long-reaching repercussions.

Johne’s disease comes to mind if there is swelling under the jaw and cows are thin, even if feed is good, and the animals are suffering from chronic diarrhea. This can happen clinically to several cows at once.

A veterinarian should test for Johne’s because if it is present, producers will want to cull the clinical cases. The veterinarian can then help decide how to best alleviate the problem.

The mouths of all animals are sensitive, including cattle, so trauma, broken jaws, broken teeth or blunt force trauma in a chute can lead to swelling. If this happens around the jaw or face, it will usually gravitate down below the jaw.

To closely examine the jaw, the animal is placed in a squeeze chute and the area is palpated. A drink water gag is inserted, which is placed between the teeth to keep the mouth open, allowing the mouth to be explored .

Tooth problems may occasionally require a rasping of the teeth, as is routinely done in horses. These cattle may also be salivating profusely because of the pain, but massive salivation also makes veterinarians think about the possibility of rabies. Although very rare, especially in Alberta, it sometimes needs to be ruled out.

A tongue that has been bitten or lacerated or has been penetrated by barley beards will also lead to swelling and salivation. Sometimes blood can be seen in the saliva.

The condition, called wooden tongue, is caused by a bacteria and will result in the tongue swelling, sticking out and having a definite wooden feel. Cows may look very thin because they haven’t been able to eat or drink, but response to treatment is very good.

Sodium iodide administered intravenously and an antibiotic often yield a cure. The sodium iodide can cause the odd abortion, but if a pregnant cow has wooden tongue and can’t eat or drink, the producer has no choice but to treat her.

Heart failure can result from a variety of situations, such as growth on the heart valves and “hardware disease,” in which metal from the stomach (reticulum) penetrates through the diaphragm and into the heart.

If it is the right side of the heart, the pressure backs up into the body, particularly up the jugular veins. This leads to vast swelling in both the brisket and under the jaw.

Veterinarians can treat this excess swelling with diuretics that remove body fluid. If multiple cases occur, look for potential sources of metal.

The flags that utility companies use to mark underground pipelines are a pet peeve of mine because if they are in a silage field, they can be chopped up by silage cutters into bite-sized pieces.

I wish these companies would use a biodegradable product rather than the thin metal stiff wire.

I recently dealt with soft swelling under the jaw in a healthy purebred bull calf. It was not an abscess and there were no other clinical signs.

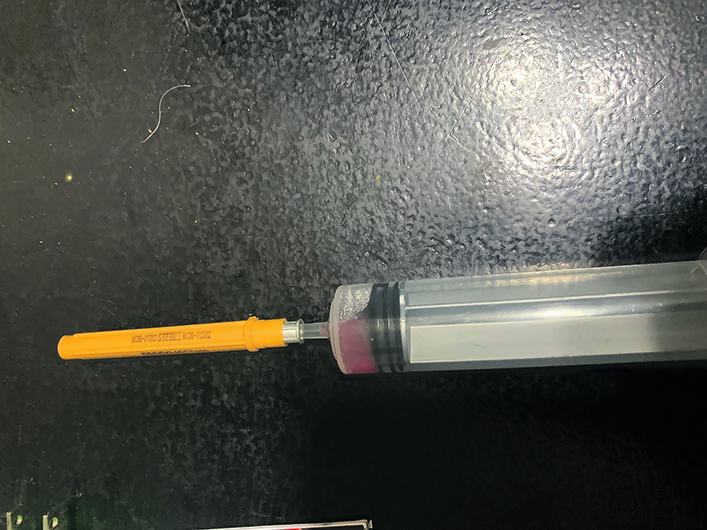

The area was clipped and cleaned, and a sterile needle was inserted, similar to what would be used to tap an abscess. This produced a mucousy, sticky, clear jelly-like fluid. It was a salivary duct rupture and the accumulation of fluid.

I have seen a few of these in dogs, but this was my first on cattle. The duct scarred up and eventually the area was thickened but fortunately did not get bigger.

Swelling under the jaw — or anywhere, for that matter — should be closely examined. The diagnosis may lead to possible prevention in the herd, especially when it comes to hardware disease.

The salivary gland rupture that I treated was a one-off but easy to diagnose once I saw the saliva.

It’s amazing what observation and an oral exam can tell us. Always look closely at these specific clinical signs because they can be caused by many things.

Roy Lewis works as a veterinarian in Alberta.