Project uses bolus technology to help identify the factors that producers could look for when acquiring replacements

A researcher wants to save cow-calf producers time and money by finding better ways for them to choose the best replacement heifers for their operations.

“We want to know if we can assess something — some traits, some indicator — earlier in the season instead of having to wait until you turn them out with a bull,” said Susan Markus, a livestock research scientist at Lakeland College in Vermilion, Alta.

About 10 to 15 percent of such heifers are subsequently found to be open, after having consumed feed during the winter followed by pasture in the summer, said Markus.

Read Also

Trump’s tariffs take their toll on U.S. producers

U.S. farmers say Trump’s tariffs have been devastating for growers in that country.

“If you’re keeping a replacement heifer, if she’s coming out of your own herd, she’s probably going to cost you about $2,000 to get her from weaning time to breeding time.”

The total expense in terms of open heifers could add up to as much as $15,000 out of a herd of 50 head at a time when cow-calf producers are facing obstacles ranging from drought to soaring input costs such as feed and fuel.

Fertility is the top economic factor for cow-calf producers, followed by production performance traits and carcass, said Markus.

“That’s why our research focuses on these reproductive traits because we want females that end up having calves, which is our income,” she said.

“And then the other piece that we need to realize is even if we found the perfect heifer, you have to realize that genetics alone is only about 25 to 30 percent of what tells you about her fertility. Seventy to 75 percent of the heifer’s fertility is really affected by the environment and the management you have her under.”

Markus is part of a nearly $1.2-million research project that is studying the problem. About $150,000 of the funding was provided by the Canadian Agri-Food Automation and Intelligence Network (CAAIN).

The three-year initiative began in December 2021 and includes a herd at the Manitoba Beef and Forage Initiatives demonstration and research farm near Brandon, said Markus. A second herd is located at a ranch near Kelowna, B.C., in collaboration with Thompson Rivers University, she said.

A third herd involves Lakeland College and a ranch in northeastern Alberta.

“We’ve had 2022 and almost 2023 for two full years of data and we’re looking for one more year before we wrap it up, and it’s going to wrap up in early 2025.”

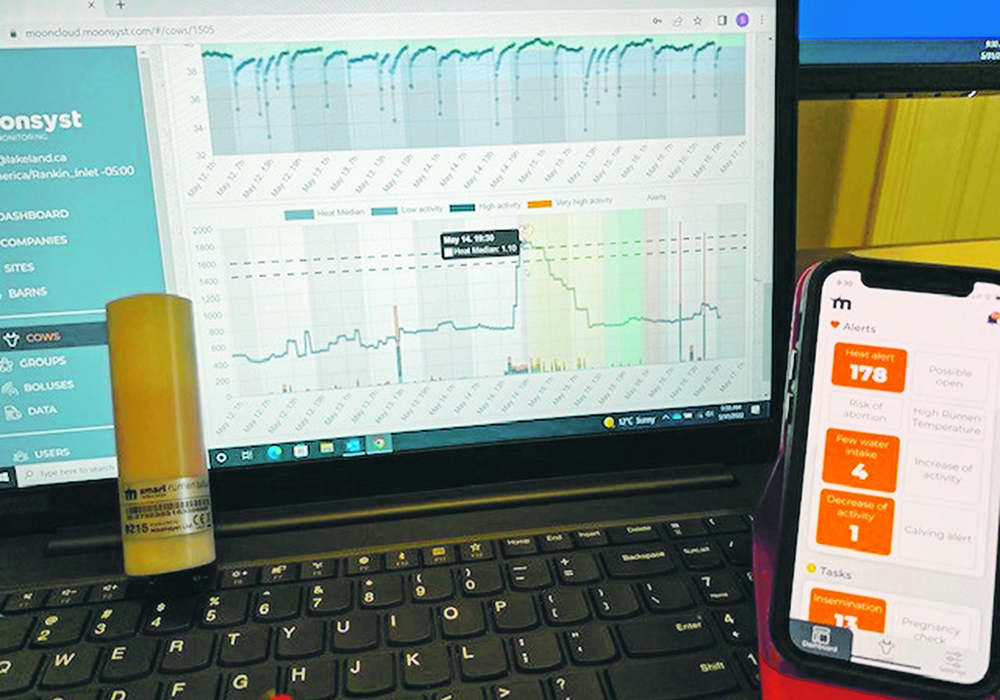

Data is being gathered partly by using wireless boluses that are permanently placed in the reticulum or second chamber of the stomach of heifers, said Markus. Boluses are cylindrical devices that are more than 10 centimetres long and about the diameter of a $1 coin, she said.

They record the activity level and internal temperature of the heifers every hour, she said.

“And from those two parameters, because these boluses are commercially available, there is an algorithm that’s been developed, but the work has been done with dairy animals.”

Dairy cows are typically housed differently than beef replacement heifers, she said.

“We’re trying to see if this temperature and activity indication that somewhat predicts estrus will work on the beef heifers.”

The boluses show increasing activity and temperature for the heifers as they reach estrus each month, said Markus.

“We have been looking at who had consistent heat cycles… and the research basically tells us what we’ve seen in the literature, which is a heifer needs to have at least two estrus cycles before she’s exposed to a bull.”

Such heifers are mature enough to become pregnant in the first or second cycle of breeding, said Markus.

“And those are the females that tend to stay in our herd for a long time compared to heifers that don’t show any estrus signs, or maybe just one cycle before we send them back out to breeding.”

It doesn’t mean the latter animals won’t conceive, but instead are likely more immature and won’t become pregnant until later, she said.

“Another rancher may breed their heifers a month later and so that heifer may work for him, so we want to know which heifers are reproductively mature enough to work in our upcoming breeding season.”

Producers traditionally have assessed heifers using two basic approaches.

“Typically, if we’re going to pick replacement heifers, a lot of producers will look at if they have existing records on them,” said Markus.

“Who’s the mother? What’s that pedigree or family that she’s from? When was she born — in the earlier part of the calving season or later — because that makes a difference about how her fertility might pan out…. But what we found was that with a lot of females is they could have good pedigrees and good genetics, but the fertility may not be there.”

Producers also use visual assessments of heifers because the animals may not always have records, said Markus. It includes when producers go to the auction market, or if they are buying the females of another cow-calf operation to place in their herds and there isn’t much data, she said.

“Conformation is number one probably because they look at the animal and they say, ‘yeah, she looks feminine. She looks like she probably is a good heifer.’ And everyone has their ideal heifer in their mind… so, this really is a cow-calf issue, especially as larger herds tend to not keep a whole lot of records.”

Scientists have found that temperament is one factor that likely comes into play for heifers, said Markus.

“Some of them are flighty, less docile animals. They just don’t gain as well, they have issues with being scared of the handling facilities, and those ones sometimes tend to be the ones that are going to turn up open more so than the calmer ones.”

Other potential factors being investigated by researchers are the replacement heifer’s size and frame score, which is a numerical description of skeletal size that aims to objectively estimate the possible growth pattern and mature size of cattle.

Markus said although producers don’t want to always pick the bigger animal, “we know we want the heifers that are born earlier in the calving season because then they should have enough age on them to be reproductively mature, meaning they will probably then be the ones that will become pregnant and conceive early in our breeding season, but size doesn’t tell that picture alone.”

Although producers could select the early-born heifers, some of the animals that are born later will still be fertile and will likely stay around the herd, she said.

“What can we assess on them to know who’s who, to know which ones have the size but not the fertility or have the fertility but not the size, or any combination of those?”