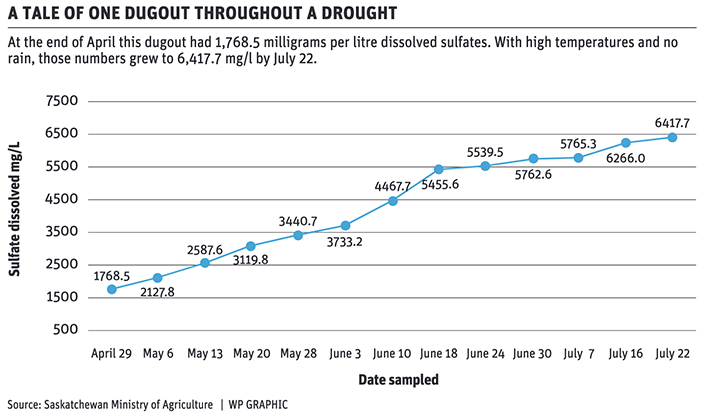

Water quality issues arise when the spring runoff is limited and showers don’t arrive to replenish evaporation and use

Prairie farmers are feeling the impact of dry wells and empty dugouts as far east as the Manitoba-Ontario border.

Aquifer recharge is not happening as it once did.

At an enormous cost, ranchers are buying big-volume tanker trailers to haul water to dugouts. Herd dispersals are now a weekly event, and it’s not likely many of those cattle producers will be back.

It’s a bleak situation. We can blame it on global warming or Mother Nature, but blaming doesn’t solve problems. It doesn’t put water back into the aquifer or surface ponds. The best we can do is do the best we can with the resources and management capabilities at our disposal.

Those resources and those management capabilities are the subject of a presentation to be given by Sask Ag livestock specialist Catherine Lang at the AIM Livestock Days at the GFM Discovery Farm on Friday 2:00 pm August 20.

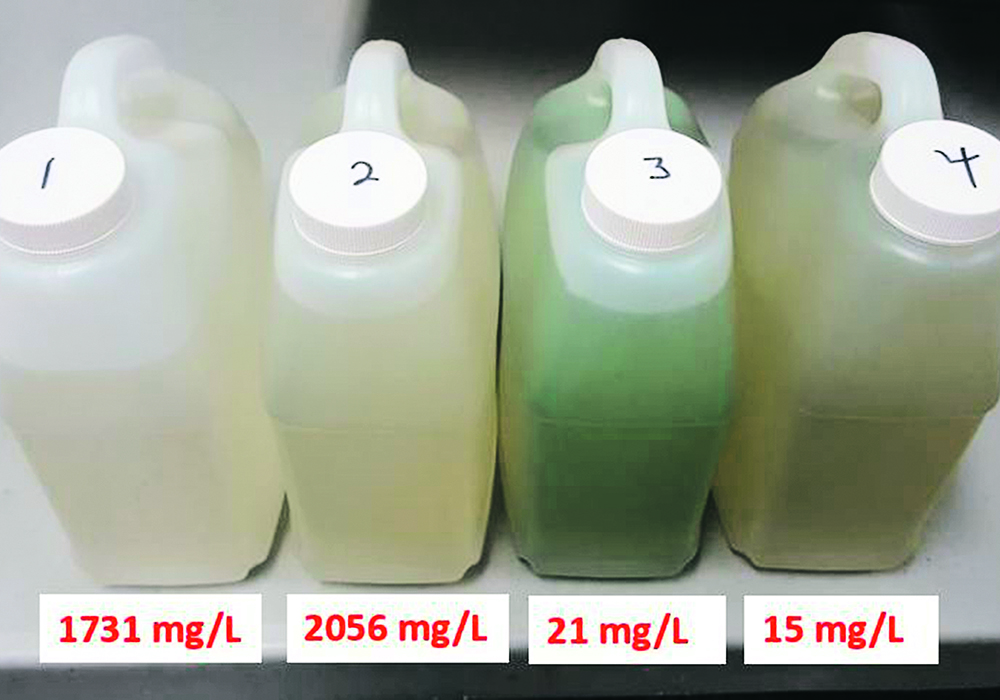

Water testing is the key to keeping your herd healthy as possible, Lang explained in a recent phone interview. She said there are a total of 17 elements that should be tested, of which six contribute most directly to cattle health.

“Iron on its own may not be a problem. Sulfates on their own may not be a problem. But there’s trouble with mineral binding when those two are together in a well,” said Lang.

Mineral binding occurs when two minerals join together within the ruminant. The cow cannot digest the combination, so the minerals pass straight through the animal digestive system and end up in the manure. The cow has gained nothing from the minerals. Those minerals can enter the cow through the water or the feed.

“Given the geography in which we live, we have saltier water and saltier forages. When we add supplemental minerals, the salts bind to those added minerals causing them to become indigestible,” said Lang.

“In water tests, we can see higher sulfate levels along with higher iron levels, in which case we recommend using a chelated mineral, which reduces mineral binding and prevents a trace mineral deficiency. But you need a test to know what’s happening with your water.

“If you have highly saline water, there’s not much you can do. You can try chelated minerals if the test allows it. But tests often show the water too high in many parameters to be safe for cattle. In drought years like this, there’s been very little rain recharge and no runoff.”

Lang said ranchers are buying highway tankers to get water out to pastures where dugouts have gone dry. There has also been an increase in the number of ranchers who have fenced dugouts and sloughs to pump water out to the cattle, thus preserving the health of the water and the health of the herd. They pump out to a watering trough to keep cattle out of the water.

“It’s really beneficial in years like this because that dugout or slough bottom becomes so muddy and contaminated by the cattle. More ranchers are managing their water with a remote system. If you’re developing a new dugout, there’s funding available to fence it and pump water out to the trough.

“We offer free water testing for ranchers. We first do an initial conductivity screening in any of the 10 regional offices in (Saskatchewan). That tells whether the water is safe for cattle or if there’s toxicity. If there are any doubts, the samples go to the lab in Regina for the full analysis. But the pre-screening is the immediate way of knowing which water is safe,” said Lang.

“I don’t have an official number, but I’d say nearly one-third of water samples we’ve seen this year are not safe for cattle.”

Lang will be speaking about water quality during the Ag in Motion Livestock Days at the Glacier FarmMedia Discovery Farm near Langham, Sask., on Aug. 20.