A film made six decades ago that featured farmers as the actors in a fictional but true-to-life story is being streamed online for the 100th anniversary of The Western Producer.

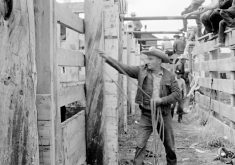

Wheat Country focused on Lloyd and Thelma Smith and their sons Allan, Murray and Barrie as they hurried to get their crop harvested before a hailstorm swept their farm near Swift Current, Sask. It was filmed in colour in 1958 by the National Film Board of Canada and released the following year.

“Here is a film which shows why, each spring, prairie farmers renew their gamble with the land, wind and weather – with frost, drought, rust and hail – for, in this most famous wheat country of the world, their optimism is more justified than not,” said a description by the NFB.

The Smith family acted in the movie for free because it was important that Canadians learned about some of the realities of being a farmer, said Murray during a recent interview.

“The only thing we got out of this whole thing is the film crew took us out for supper before they left to go back down east, but we didn’t get a nickel for it.”

The 20-minute movie can be viewed for free as part of Perspectives from the Prairies, which is a year-long series of monthly films compiled by the NFB in honour of the 100th anniversary of The Western Producer. The initiative was launched Aug. 24 with the film, Corral (1954).

Wheat Country is being shown with Grain Handling in Canada, a 24-minute colour documentary released in 1955. The latter film depicts an era of wooden prairie elevators when steam locomotives were still being used to haul grain to what is now Thunder Bay, Ont.

NFB collection curator Camilo Martin-Florez and publicist Katya De Bock selected the two films for September because they each underline the importance of each year’s harvest not only to farmers, but to Canada’s economy.

Wheat Country is particularly significant because the Smith family were non-professional actors portraying a story set on their own farm that could have been taken from their actual lives, said Martin-Florez. He called it a rare gem because it is one of the few neorealist-style fiction films ever made by the NFB about the Prairies.

The making of Wheat Country was led in 1958 by Quebec director Roger Blais, who was honoured with the Order of Canada in 2000 and died at age 95 in 2012. The film has been dubbed into languages ranging from Punjabi, Italian and Turkish to Dutch, Portuguese and French.

Besides showing how Prairie farmers must be resilient when faced by bad weather, the movie detailed how then-modern equipment such as the family’s Cockshutt combine enabled two people to do the work of a 20-member threshing crew.

Murray, who didn’t retire until he was about 80 years old, said it is incredible how much technology has advanced since the 1950s. He quit trying to operate combines when manufacturers came out with machines that contained three computer screens.

“And I said, ‘boys, I’m done. That’s too much for me’ … When you look at the cab of the tractors and the combines, of the technology that’s in them right now, it is just absolutely mind boggling.”

Wheat Country was filmed when farm families founded by pioneer homesteaders – who had initially lived in structures as simple as sod shacks – now found themselves enjoying greater prosperity. The Smith family are shown with conveniences such as an electric refrigerator, stove and TV that today are taken for granted.

Their farm did not get electricity until the late 1940s, instead relying on coal oil lamps for light, said Murray. The Great Depression of the 1930s was particularly hard on his mother, Thelma.

“(My father) was kind of a horse trader, so he could take the ups and downs of things much better than what my mother could because she had three boys that she had to clothe and feed and look after, and there was just never any money there.”

Thelma used to say she hated to see an unfamiliar vehicle drive into the yard because it was probably a banker or creditor, said Murray.

“And she even told the story of one time a banker came out to get some money on a loan that Dad had, and they had no money and that dog-gone banker, he grabbed half a dozen chickens and he threw them in the trunk of his car and went home.”

Murray described his mother as a wonderful woman who lived to be 102 years old. She died in 2008 and her husband, Lloyd, died at age 85 in 1983. Although Wheat Country is narrated from Thelma’s point of view, the actual voiceover was supplied by a professional actress.

The family did not have any dialogue in the film, and effects such as hail were created using rock salt spread by an old forage harvester, said Murray. A segment showing a window being broken was caused by people throwing rocks, and rain was supplied by the Swift Current Fire Department, he said.

However, the Smith family worked with the film crew to ensure the movie was an accurate portrayal of life on a prairie farm.

“We’d say, ‘whoa, take your pictures if you want, but don’t include that on the film because that’s not right’.”

One of the pleasures of watching the film in 2023 is seeing the city of Swift Current as it was in 1958. However, there is poignancy in noting the grain elevator shown in nearby Beverley is now gone, along with most of the rest of that community, said Murray.

A trend underlined by the film, of the closure of businesses in small communities because farmers were able to do their shopping in larger centres, intensified in the years that followed, he said.

“There’s not very many people that live in – like, all the small towns around the country now, since they pulled down the elevators. They’ve just dwindled down to nothing.”

All three of the Smith brothers are retired, along with the next generation, Doug and Stuart, who took over the operation from Allan and Murray. The land, owned by the family since 1918, is being farmed by renters.

Each generation has been encouraged to follow their own path, and “none of the grandchildren show an interest in the farm,” Smith said.

When Murray graduated from university in 1954, his father sold him a quarter section of land for $2,500. A quarter section can now cost as much as $800,000, with farmers also facing soaring costs for fuel, fertilizer, chemicals and machinery.

“Family farms are a great way to farm, but I think it’s getting less and less. It’s becoming more of corporate farms versus family farms.”

To watch Wheat Country and Grain Handling in Canada, visit www.nfb.ca/channels/perspectives-from-the-prairies/.

This column is part of a year-long collaboration between The Western Producer and the National Film Board of Canada celebrating the newspaper’s 100th anniversary.