The issue of farm families being isolated from neighbours, communities and services had been a concern since the Canadian Prairies were first settled.

In the 1950s, many roads were still little more than trails and were often impassible during rainy weather, spring thaws and heavy snow. This didn’t stop farmers from purchasing automobiles. By 1951, 57 percent of Saskatchewan farmers owned one.

On Feb. 16, 1950, Emmie Oddie shared in her weekly column that they were unlikely to have any visitors at their farm “for the house is a half mile from the road and that half mile is a wilderness of snowbanks.”

She continued that they had pulled the car out with a team of horses a few days earlier and that she and her three-year-old daughter had waited in the car while her husband took the team back to the barn and then wallowed back through the snow drifts. They eventually made it to town.

Upon returning home later that evening, they left the car at the end of the lane and walked in through the snowbanks with their purchases.

Oddie, a nutritionist, and her husband, Langford, were young farmers who had just moved to the 40-year-old family farmstead at Milestone, Sask., in the fall of 1949.

Her personal comments in her columns were reflective of what other farm families were experiencing. Her columns recounted their home remodelling efforts of building kitchen cupboards and redesigning a closet to hold linens. In May of 1950, workmen wired the house in preparation for the completion of the high wire line to the farm.

“We are still pinching ourselves. How we appreciate the new fluorescent lights. I wish you could all share with us the benefits of electricity on the farm,” Emmie shared in her Aug. 31, 1950, column.

As building materials became more readily available in the 1950s, farmstead remodelling and new building increased. A new column entitled “Engineering for the Farm” was added to The Western Producer with a focus on all things related to the building of new farm homes and buildings, from how to prepare and build the foundation to the selection of lumber and the installation of electrical and plumbing services.

The federal and provincial governments and the Central Mortgage and Housing Corp. created the prairie rural housing committee. Following research and design testing, they developed information and plans for farm water and sewage systems, efficient wall construction methods to combat cold prairie winters, farmhouse plans, farm kitchen designs and information on remodelling farm homes.

Electricity to a farm provided many new opportunities. Light in the barn, yard and home made working safer and easier. Electric appliances in the home like a refrigerator, stove, iron and washing machine saved time and energy.

The greatest addition that electricity brought was the water pump, giving water at the turn of the tap. An American study referred to in the Nov. 10, 1949, Rural Electrification supplement in The Western Producer concluded that the “biggest timesaver is the electric water system, which saves 28 eight-hour days (of labour) a year.”

Public health records showed that the health conditions of a family who had switched to running water improved by 50 percent. When the water had to be pumped by hand and carried in pails the family used as little water as possible. When the water was piped into the home, and available with the turn of a tap, more water was used (Nov. 10, 1949).

Water to the house is one thing but the removal of the wastewater was generally via a drain pipe out the wall and bathroom waste carried out in a pail. In 1959, the Saskatchewan government announced that with farm electrification in the final stages, its focus would shift to rural sewage and water systems.

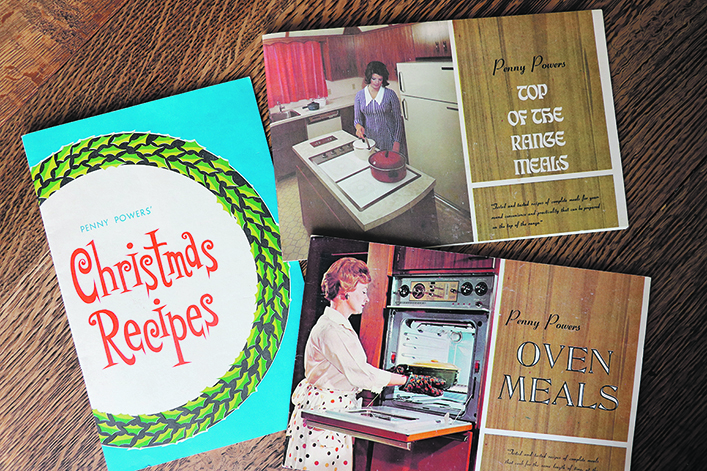

To help rural women adapt to the new electrical appliances in their home the Saskatchewan Power Corp. created Penny Powers in 1956. Manitoba Power had a similar Elizabeth.

Lillian McConnell, a home economist, was the first Penny Powers. She played a key role in the promotion and education of electrification in Saskatchewan’s rural communities.

Travelling several days a week, she took her knowledge to fairs, schools and community hall cooking events to demonstrate to rural homemakers how to use the new gadgets and adapt their recipes. As Penny Powers, she also wrote and edited numerous cookbooks, pamphlets and articles, and hosted television shows.

Electrification was a switch for many women who had been using coal or wood stoves, and who had been canning most of their garden vegetables. To provide answers to questions about freezing foods, Dr. Edith Rowles of the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Home Economics conducted a six-year research project on freezing food.

Several years of trials were necessary to obtain conclusive results because growing conditions affect quality and yield. The booklet was available from the University of Saskatchewan Extension office (Nov. 12, 1959).

Many communities were also building community halls, curling and skating rinks through co-operative efforts and financial support from community members. Electricity for water pumps and lights made these facilities usable in the evenings. They became gathering spots for community members, young and old, to share recreation, fun and fellowship.

Many new products came on the market because of developments made during the war. Non-soap detergents had been developed to replace traditional fat-based soaps. Synthetic textiles, such as nylon, were being used for items such as upholstery and ladies’ stockings. Plastics were entering the market as non-breakable dishes, tablecloths and toys.

A series of articles entitled Design for Living focused on encouraging consumers to look at the design of new products and to consider safety, ease of use and cleaning, with the objective of selecting articles that “look better and work better”.

A March 24, 1955, article highlighted plastic baby bottles as a new product. The Canadian baby boom years, based on live birth statistics, were 1952 to 1965. It was a period of good economic growth providing abundant food, good housing and stable incomes that allowed for at-home moms.

For rural women, new or remodelled homes with many labour-saving devices also offered a less burdensome lifestyle.

Other interesting changes during the 1950s included the popular Farm Boys and Farm Girls Clubs being combined in 1952 and renamed 4-H Clubs.

Television became available in larger urban centres with CKCK-TV Regina first airing on July 28, 1954, and CFQC-TV Saskatoon on Dec. 5, 1954.

Ready-to-make pizza mixes started to appear on grocery shelves in 1959.

Betty Ann Deobald, one of The Western Producer’s TEAM Resources columnists, will write a monthly column for the next year examining rural life in each decade of the last century.