Balancing work and home | Continuous cropping allows full-time farmer to make better use of time, land and equipment

LANDIS, Sask. — A cool spring wind sweeps across the open landscape of Jeffrey Wheaton’s farmyard as he reflects on his recent switch to direct seeding.

“It’s definitely nice to see the land not moving,” he said.

With the exception of trees planted on sparse home quarters in this west-central region of Saskatchewan, there are few other windbreaks.

Continuous cropping allows full-time farmers like Jeffrey to make more money on his farm, which seeds almost 3,000 acres of canola, wheat and lentils annually.

Read Also

Know what costs are involved in keeping crops in the bin

When you’re looking at full bins and rising calf prices, the human reflex is to hold on and hope for more. That’s not a plan. It’s a bet. Storage has a price tag.

Canola is his highest value crop, but lentils fix nitrogen in the soil and helps the other crops flourish.

Jeffrey splits his time between the farm and a home in Battleford, Sask.

Commuting has long been a part of farming for the Wheatons, who always maintained the house on the farm for overnight and weekend stays.

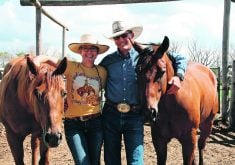

Jeffrey’s parents, Margaret and Donald, lived in Biggar, Sask., where his mother continues to work as a pharmacist, and he and Lori Rissling, a Grade 1 teacher in Battleford, recently built a home in that town.

Rissling grew up on a farm near Denzil, Sask., so understands the seasonal nature of grain farming.

“I understand how busy he is and that there are some busy times,” she said.

Jeffrey considers both women part of his “team,” saying visits to bring meals and other support help him continue to farm along with employees.

His grandfather homesteaded the farm in 1908 after migrating from New Brunswick, staying just long enough in Manitoba to be turned off by flooding and cereal rust.

Jeffrey also had a circuitous route to this farm, first graduating with a commerce degree and working in Calgary, before returning to the farm in 1994.

“Dad wasn’t the kind of guy to put pressure on you but felt I should try (farming),” said Jeffrey.

“I started because Dad wanted me to and then I found out it’s a good business. It’s my own. If I make a decision, I have to live with the consequences. If times are good, the reward is mine.”

Upon his return to Saskatchewan, he renewed his relationship with Rissling. She decided the precariousness of rural school enrolments made Battleford a safer career choice than a school closer to the farm.

Jeffrey stressed the need for an off-farm job.

“Someone should have one. It brings the stress levels way down. The farm can eat every cent you have, even in the good times.”

Commuter farming means less time for the couple to be together during the production season, when they miss out on some social events. However, it allows for more time in winter, which included a trip to Hawaii last Christmas.

Margaret said her son has made it possible for him to farm.

“He’s had to make good decisions and give up things he wanted to do,” she said.

Margaret valued post-secondary education for her children, saying it helps them better understand business. As a young bride, Margaret considered living on the farm but decided homes held their value better in town. She also thought living in town would allow her children to participate in more sports and community events and cut down on travelling time to activities.

The farm road is fraught with bumps, she conceded.

“With the farm, you’re never going to be even all the time. The good times have to look after the bumps that may come, but even the bad times are good.”

Jeffrey’s sister, Jennifer, has a career as a paramedic in Edmonton so the farm may end with him.

“If I had children, I don’t know if I would want them to (farm),” he said.

For now, he plans to continue to upgrade equipment and improve grain storage but sees little changing in the distant horizon.

“We’ll keep doing what we’re doing, he said. “There’s not a huge plan to change the business.”