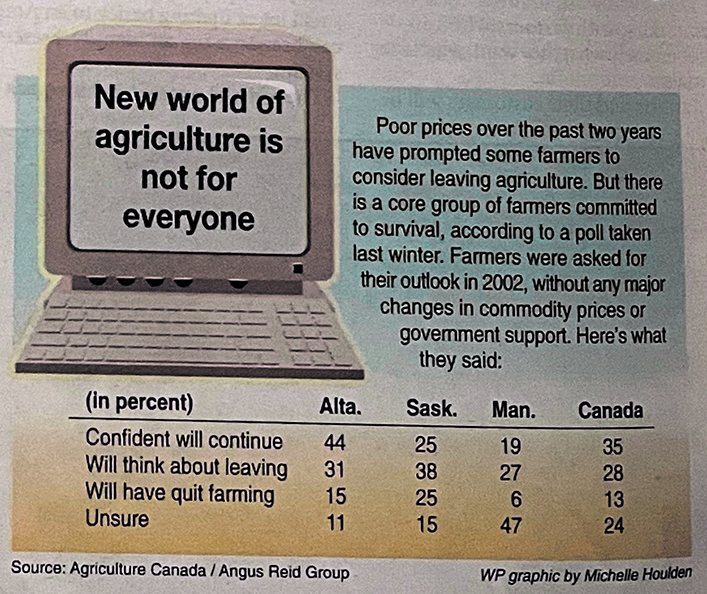

Research, technology and consumer trends in the 2000s were creating opportunities and different farming options for western Canadian farmers and their families.

At the University of Saskatchewan, facilities were being built and expanded that would facilitate research and biotech product development.

The Canadian Light Source facility would provide scientists with clear images of the inner structure of animal and plant tissue for disease and genetic research, while an expansion to the U of S’s Plant Biotechnology Institute (PBI) was intended to fill the gap between basic biotechnological research and commercial production of biotech products.

Read Also

Restaurant blends zero waste, ancient farming

A Mexico City restaurant has become a draw for its zero-waste kitchen, which means that every scrap of food and leftovers is reused for other purposes.

PBI at that time concentrated on fundamental genetic engineering, in which useful genetic traits in plants were studied, isolated and exploited. The institute was well known for its work with canola.

“Our economy has been transformed from wheat fields and primary agriculture to new strengths like ag biotech, food processing and information technology,” Saskatchewan economic development minister Janice MacKinnon was reported as saying in the July 13, 2000, issue of The Western Producer.

Farmers across the Prairies were adopting sustainable farming practices, such as zero-tillage, to reduce soil erosion, improve soil health, increase crop yields and conserve moisture. Low grain prices and the loss of the Crow Benefit transportation subsidy prompted many farmers to switch to higher-value crops such as canola, canaryseed, peas and lentils.

More farms were growing in size to gain an economy of scale, and there were fewer, but larger grain elevators. Both factors added to the depopulation of the rural countryside and led to the disappearance of smaller communities and their services such as schools, stores, hospitals and post offices.

Prairie provincial governments were working to bring high speed internet access to rural areas. Better access would open opportunities for distance education, telemedicine and e-commerce. Rural high school students would be able to access more courses through distance education, and the internet would bring the world to the farm office. Farmers could now surf the internet for information such as commodity prices, weather reports and equipment and parts purchases and do online banking.

The ultimate in long-distance telephone conversations took place Sept. 23, 2009, at the high school in Vulcan, Alta., when four astronauts from the International Space Station held a 20-minute conversation with students. The school district had been chosen over thousands of others across the country because of its use of technology to link 6,200 young people via the internet, video conferencing and other innovative ideas, according to a story in the Oct. 1, 2009, issue.

Farm equipment was being designed to not only meet the needs of new farming methods but also to make the long hours in the tractor or combine more comfortable and to accommodate other family members easily and safely in the cab. Combines now came equipped with global positioning systems, technology for producing yield maps and sophisticated internal monitoring systems.

There was a growing concern among consumers about what they were eating and if it was chemical and pesticide free.

“People were saying, ‘hey, I’m going to think twice about eating this,’ ” said Erna Van Duren, who researched environmental food marketing at the University of Guelph.

Added Martin Entz from the University of Manitoba: “Some farmers had already started to find opportunities in consumers’ attitudes. Organic farmers had become experts at seeing consumers’ opinions as a market rather than a problem to overcome.”

The U of G’s Dave Sparling noted in the Aug. 3, 2000, issue “that organic food was the fastest growing segment in food marketing.”

Consumer interest in nutraceuticals, which are foods that cure what ails you, was prompting the U of M to plan a $23 million research centre. Agriculture dean Harold Bjarnason said he wanted to tie agriculture to preventive medicine, and lay the groundwork for farmers to produce more specialty crops.

The centre would also focus on proving the safety of genetically modified foods, he added.

Crops in the new world of agriculture would also go beyond food as consumers wanted industry to find more environmentally friendly materials and plant-based products.

Winnipeg consultant Brian Kelly pointed in an April 10, 2000, issue to pollution from fossil fuels and predicted that, depending on government policy, farmers could eventually be delivering grain to as many as 10 ethanol plants in Western Canada.”

In May 2003, disaster struck the Canadian cattle industry when a cow from northern Alberta was found to have BSE. The United States and 40 other countries immediately closed their borders to Canadian cattle.

The collapse of the cattle markets created a desperate situation for farmers and their rural communities. In June 2003, Alberta feedlot owner Rick Paskal began delivering 10-pound packages of frozen ground beef to eager customers for $1 a pound.

As of Jan. 1, 2010, all Canadian cattle leaving the farm would require to have electronic identification tags. This requirement was designed to help move the beef industry toward full traceability. With higher international and domestic standards for animal health and food safety, it had become essential to be able to trace back an animal if a disease was found at the packing plant.

With the new tags trace back could occur in about six seconds. There was still more work to be done to trace the animals every time they got on and off a truck, but the technology, at that point, had not advanced enough to do that, according to an Oct. 8, 2009, story.

A study about farm women’s lives by two University of Regina researchers, Wendee Kubik and Robert Moore, stated that “farm women are often the ‘invisible partners’ contributing and maintaining the farm.” This means researchers and policy makers often ignore them.”

They recommended making sure policy-makers and health-care workers learned about farm issues.

Other suggestions included taking mobile services such as the mammogram van to rural districts and creating local centres to supply services such as nurse practitioners, counselling, child care and job and educational courses, according to a May 31, 2001, story.

In Miami, Man., a day care and nursery school opened in the spring of 2000 for farm families. The Miami Children’s Facility Inc. was geared to work around parents’ busy schedules, said director Donna Riddell.

“We have to be more flexible and more accommodating due to the often unpredictable working hours of rural parents,” she said in a Sept 28, 2000, story.

To create awareness that prime agricultural land was in danger of being paved over by urban encroachment, Gordon Visser organized the Great Potato Giveaway northeast of Edmonton in the fall of 2009. He wanted to inform people that a good part of Edmonton was built on really nice agricultural land and that the land had produced vegetables for generations.

Farmland prices were increasing due to development and the worldwide demand for food.

Non-farmer investors were looking at farmland as an attractive investment. A non-farmer landowner could lease the land to a farmer for a steady income and make a profit when land prices rose, or an investor group could farm the land itself, taking advantage of economies of scale.

The Western Producer reported that increasing land prices were driving land out of the reach of farmers, especially young farmers.

Betty Ann Deobald, one of The Western Producer’s TEAM Resources columnists, will write a monthly column for the next year examining rural life in each decade of the last century.