MATTITUCK, N.Y. — Certified organic hops growers on Long Island have found their niche within a niche in microbreweries and the demand for locally made products.

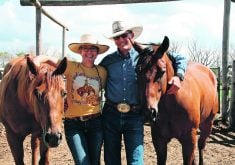

Marcos Ribeiro and Pat Libutti of Craft Master Hops grew 12 acres of hops in their first year and will add another six this spring.

“Organic breweries have a hard time finding certified crops so we get a premium from these,” said Ribeiro of his U.S. Department of Agriculture certified organic hops.

It’s a tough row to hoe for the growers, who hand weeded the crop last year and installed 1,100 non-treated poles held in place by guy wires.

Read Also

Know what costs are involved in keeping crops in the bin

When you’re looking at full bins and rising calf prices, the human reflex is to hold on and hope for more. That’s not a plan. It’s a bet. Storage has a price tag.

They spend about a month stringing coconut fibre imported from Sri Lanka between poles and more time training the vines to grow along these supports.

They employ two full-time workers and will add another this year.

Ribeiro thinks it’s worth the extra time and effort.

“It’s a small microcosm, but eventually it will pick up like organic produce,” he said.

Added Libutti: “We really enjoy what we do and that’s what motivates us.… It’s our business and like any business, there will be highs and lows. Especially when harvesting, there’s a lot of work to do but it has to be done.”

Organics is a lifestyle choice for the two men and their families, who live a short commute from the farm.

“It’s a more pleasant experience on a daily basis,” said Libutti, who used to work in real estate development and construction.

Ribeiro, who got his start growing mushrooms, greens and tomatoes, also operates a masonry company, agreed.

“Once you get into the business, you learn how vegetables and crops are treated and you want to push organics,” he said.

Added Libutti: “We believe the plants grown will have a purer taste.”

In addition, they say the industry is moving toward measuring pesticide and herbicide levels in crops.

Their crops include Cascade, Centennial, Chinook and CTZ varieties, all of which will take four years to reach full production.

Hops plants grow back from the root beginning in April and can live for decades. Starting in late August, a hedge trimmer is used to cut near the base before the harvester enters the rows.

“If you cut all the way down, you’re doing the plant a disservice. All growth to six or seven feet is based on last year’s reserves,” Ribeiro said.

“Like asparagus, the colder it is, the slower it grows.”

Their farm was previously used as a dump site, so the pair spent eight weeks removing 1,000 garbage bags of debris.

The upside was the six million pounds of good compost found on good-draining, rich, dark loamy soil in this sunny microclimate .

Agricultural land in the area starts at about $25,000 per acre so they are leasing 18 acres this year to try their hand at growing malting barley.

Ribeiro said their investment also included a 10,000 pound harvester, “half a bus in size,” which separates the leaves from the cones, a dryer, a pelletizer and a large walk-in refrigerator for storage.

Yields for conventionally grown hops are 1,900 lb. per acre, while organic crops yield about 30 percent less, he said.

Their farm was assisted by New York’s recent craft brewers bill.

The legislation is designed to support the state’s breweries and wineries, increase demand for locally grown farm products and expand industry-related economic development and tourism.

It protects a tax benefit for small breweries that produce beer in New York, exempts breweries that produce small batches of beer from paying an annual state liquor authority fee and creates a farm brewery licence that will allow craft brewers to expand their operations, open restaurants or sell new products.

Ribeiro conceded it’s tough to get into agriculture as an outsider.

“People won’t give you opportunities. It’s a barrier to entry when you don’t know people,” he said.

“Once you show you’re in and it’s for real, opportunities do open up.”

Libutti saw an opportunity for proprietary rights in planting hops breeders’ research plots and acquiring naming rights on what they grow. Brewers who obtain exclusive rights to this new crop can promote that in their marketing strategies.

“It brings in a variety not being grown where we are before and brewers will have another variety option,” he said. “In that business, they are always looking for something new and different.”

The partners sell both wet and dry pelletized hops to local breweries. Ribeiro said the wet ones are time sensitive and must be cut and used the same day.

“It brings out flavour you can’t get with pelletized hop.”