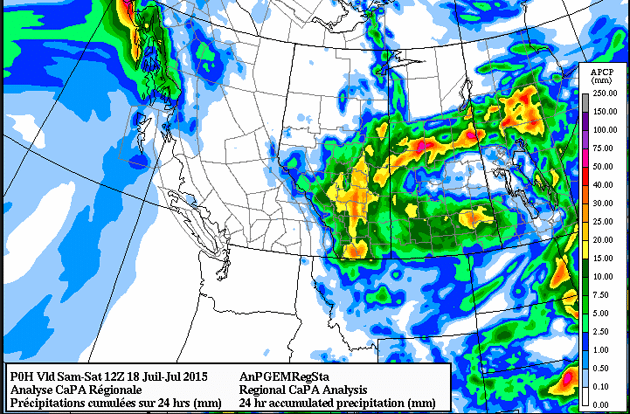

Friday July 17 was an unusual day in the western Prairies for its extended rainfall over fairly wide areas.

Most of the rain in the region this summer has come from intense thunderstorms, but the system Friday caused several hours of rain in some areas.

Environment Canada in Alberta recorded 30 millimetres at Red Deer, 29 mm at Camrose, 28 mm at Edmonton, 25 at Drumheller, 21 at Vegreville, 16 at Lethbridge and 11 at Medicine Hat.

In Saskatchewan, Rosetown got 23 mm, Kindersley 17, Swift Current six and Saskatoon five. Heavier rain in northern Saskatchewan helped knock back the forest fires in the region.

The following Environment Canada map shows heavier rain in yellow and red.

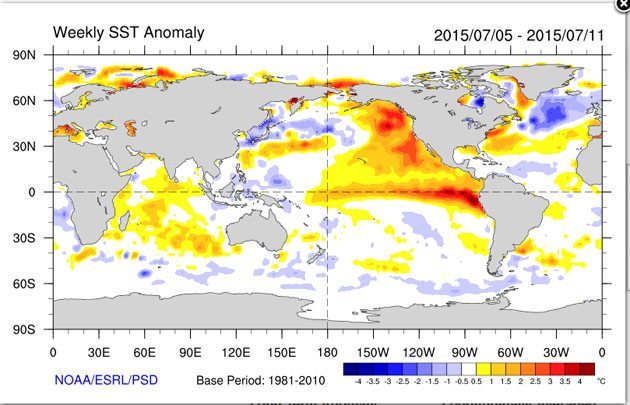

One of the factors contributing to this summer’s dry conditions in the western Prairies is what has been dubbed “The Blob,” an area of unusually warm water off the coast of British Columbia.

Environment Canada senior climatologist David Phillips told the Edmonton Journal earlier this year that the El Nino and this blob of warm water in the north east Pacific could be complementing each other and the result is the dry spring and summer in much of the area west of the Saskatchewan-Manitoba border

This map from The Earth System Research Laboratory of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows the warm water off the B.C. coast.

The history of the blob is set out in this April 9 release from the University of Washington’s publication UW Today.

‘Warm blob’ in Pacific Ocean linked to weird weather across the U.S.

By Hannah Hickey

The one common element in recent weather has been oddness. The West Coast has been warm and parched; the East Coast has been cold and snowed under. Fish are swimming into new waters, and hungry seals are washing up on California beaches.

A long-lived patch of warm water off the West Coast, about one to four degrees Celsius above normal, is part of a larger pattern driven by the tropical Pacific that’s wreaking much of this mayhem, according to two University of Washington papers to appear in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

Read Also

Alberta Crop Report: Harvest more than three-quarters finished

Alberta’s provincial harvest as of Sept. 23, 2025 was 78 per cent complete, said the province’s weekly crop report.

“In the fall of 2013 and early 2014 we started to notice a big, almost circular mass of water that just didn’t cool off as much as it usually did, so by spring of 2014 it was warmer than we had ever seen it for that time of year,” said Nick Bond, a climate scientist at the UW-based Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean, a joint research center of the UW and the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Bond coined the term “the blob” last June (2014) in his monthly newsletter as Washington’s state climatologist. He said the huge patch of water – 1,000 miles in each direction and 300 feet deep – had contributed to Washington’s mild 2014 winter and might signal a warmer summer.

Ten months later, the blob is still off our shores, now squished up against the coast and extending about 1,000 miles offshore from Mexico up through Alaska, with water about two degrees C warmer than normal. Bond says all the models point to it continuing through the end of this year.

The new study explores the blob’s origins. It finds that it relates to a persistent high-pressure ridge that caused a calmer ocean during the past two winters, so less heat was lost to cold air above. The warmer temperatures we see now aren’t due to more heating, but less winter cooling.

Co-authors on the paper are Meghan Cronin at NOAA in Seattle and a UW affiliate professor of oceanography, Nate Mantua at NOAA in Santa Cruz and Howard Freeland at Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans. The study was funded by NOAA.

The authors look at how the blob is affecting West Coast marine life. They find fish sightings in unusual places, supporting recent reports that West Coast marine ecosystems are suffering and the food web is being disrupted by warm, less nutrient-rich Pacific Ocean water.

The blob’s influence also extends inland to affect West Coast weather. As air passes over warmer water it picks up heat, resulting in a tendency for warmer temperatures and reduced mountain snow packs, which may be exacerbating current drought conditions along the West Coast.

The blob is just one element of a broader pattern in the Pacific Ocean whose influence reaches much further – possibly to include two bone-chilling winters in the eastern U.S.

A study in the same journal by Dennis Hartmann, a UW professor of atmospheric sciences, looks at the Pacific Ocean’s relationship to the cold 2013-14 winter in the central and eastern United States.

Despite all the talk about the “polar vortex,” Hartmann argues we need to look south to understand why so much cold air went shooting down into Chicago and Boston.

His study shows a decadal-scale pattern in the tropical Pacific Ocean linked with changes in the North Pacific, called the North Pacific mode, that sent atmospheric waves snaking along the globe to bring warm and dry air to the West Coast and very cold, wet air to the central and eastern states.

“Lately this mode seems to have emerged as second to the El Niño Southern Oscillation in terms of driving the long-term variability, especially over North America,” Hartmann said. The research was funded by the National Science Foundation.

In a blog post last month, Hartmann focused on the more recent winter of 2014-15 and argues that, once again, the root cause was surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific.

That pattern, which also causes the blob, seems to have become stronger since about 1980 and lately has elbowed out the Pacific Decadal Oscillation to become second only to El Niño in its influence on global weather patterns.

“It’s an interesting question if that’s just natural variability happening or if there’s something changing about how the Pacific Ocean decadal variability behaves,” Hartmann said.

“I don’t think we know the answer. Maybe it will go away quickly and we won’t talk about it anymore, but if it persists for a third year, then we’ll know something really unusual is going on.”

Bond says that although the blob does not seem to be caused by climate change, it has many of the same effects for West Coast weather.

“This is a taste of what the ocean will be like in future decades,” Bond said. “It wasn’t caused by global warming, but it’s producing conditions that we think are going to be more common with global warming.”