Herbicide-resistant weeds cost Canadian farmers more than half a billion dollars annually and the price tag is growing. The next generations of producers might not be any better able to control the problem than we are today.

There are wild oat populations displaying resistance to Groups 1, 2, 8, 14, and 15 herbicides, kochia populations showing resistance to Group 2, 4 and 9 herbicides, and Palmer amaranth has reared its ugly head in a Manitoba field. In the United States, Palmer has shown resistance to Group 2, 3, 5, 9, 14 and 27 herbicides.

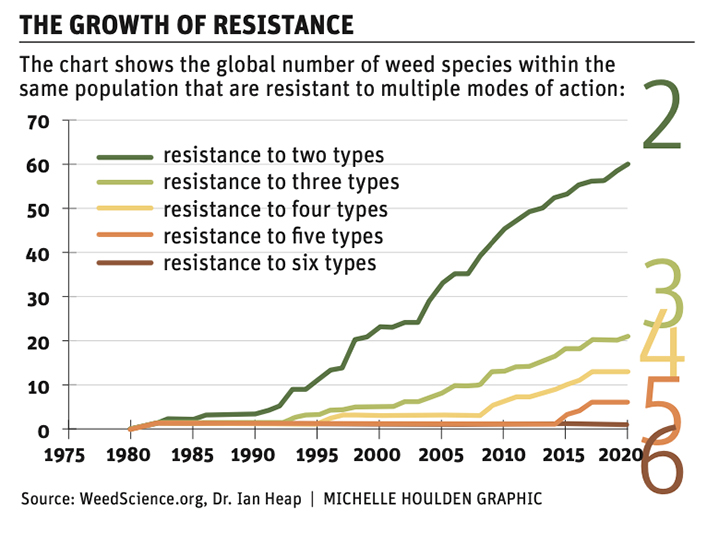

The Canadian experience fits the global trend. The International Survey of Herbicide Resistant

Read Also

Saskatchewan project sees intercrop, cover crop benefit

An Indigenous-led Living Lab has been researching regenerative techniques is encouraging producers to consider incorporating intercrops and cover crops with their rotations.

Weeds keeps a running tally of weed species with multiple resistance.

To the end of 2020, the survey documented 60 weed species around the globe with resistance to two modes of action, 21 resistant to three modes of action, 13 resistant to four modes of action, six resistant to five modes of action, and one weed species resistant to six modes of action.

Canada now has 51 weeds resistant to at least one mode of action, which places it third on the global list behind the U.S., which has 123 herbicide-resistant weed species, while Australia has 89.

Clark Brenzil, provincial specialist in weed control at Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture, said the best way to reduce the losses from herbicide-resistant weeds is to stop them from establishing a foothold.

“Pre-emptive activity is the key to success here. Waiting for something to show up before you take action is a recipe for failure with respect to herbicide resistance,” he said.

“Once you see it, it’s already so well established in the field that you’re not going to be able to turn the clock backward.”

The most common approach to combating herbicide resistance is using a diversity of herbicides, including herbicide layering where multiple modes of action are deployed at the same time.

However, a 2017 paper by Hugh Beckie and Neil Harker about the top 10 herbicide-resistant weed management practices, said herbicide diversity is not enough to stop the spread.

“Crop diversity ideally entails weed-competitive species and those with varied growth cycles and phenologies: a mix of dicots and monocots, winter and spring planted, cool and warm season or annuals and perennials,” the paper stated.

“Although herbicide diversity is enabled by crop diversity, the latter enforces different seeding and harvesting dates and exerts different selection pressures on weed communities with each different crop. Perennial crops are especially effective in managing annual weeds.”

Putting a field with problematic weeds into alfalfa for a few years is a tried-and-true method to clean up a field that also has other benefits like better water infiltration created by the forage’s deep roots.

But this can be a tough recommendation for agronomists to give their customers.

Most grain operations don’t have the equipment necessary to produce forages. Harvest timing can conflict with their other farming operations, including fungicide season, and taking a field out of grain production will hurt a farm’s bottom line in the short term if the forage yields don’t pan out.

Therefore some farmers have built relationships with local livestock operations or custom forage producers to help them keep weed pressure in check.

Beven Kelbert farms in the Swan River, Man., region and he’s worked with a livestock operation to help clean up some of his crop land by producing silage on it for a few years.

“A lot of the perennial weeds or annual weeds that do come, this sure thins them out. On that ground there was Group 1 resistant wild oats. Honest to God, it would come up like lawn. They would silage it off and always catch it before it set seed,” Kelbert said.

“The next year, I could go through with one pass of Liberty on canola and you couldn’t see a wild oat on it.”

He said building mutually beneficial relationships with neighbours can be an excellent way to combat herbicide-resistant weeds. Beyond renting or trading land with a livestock operation, establishing a market with a livestock operation for crops not typically grown on a farm can help change up selection pressure applied to weeds.

Brian Tischler farms with his neighbour, Will Groeneveld, near Mannville, Alta., and they took this idea to another level when it comes to their relationship with a neighbouring livestock farmer, Glen Smith, who has about 1,000 head of cattle and boards another 1,500.

“We grow oats for him, and we plant his corn and take care of his plants. He doesn’t like plants, we don’t like animals,” Tischler said.

He calls the model a mixed-collaborative farm, which provides excellent synergy because each person can focus on what they do best.

“We have a market then for our oats, it allows us to have a good five-year rotation on our land, it gives us cropping options. We can grow grazing corn on our land that’s fenced and he can chase his cows on there and we grow some grain on his land then. So, we share back and forth,” Tischler said.

Including winter annuals in the rotation can also disrupt annual weed populations, said Charles Geddes, research scientist at Agriculture Canada. One of his studies has a rotation with spring wheat, canola, spring wheat, lentils, as well as a winter wheat, canola, winter wheat, lentil rotation.

The study examines how alternating crop life cycles within the crop rotation affects the kochia weed population.

Winter wheat gets going early in the spring and can get a significant advantage over the kochia.

“We’re into the third year of the rotation this year and I couldn’t even find kochia in any of the winter wheat plots, so it is working quite well to mitigate kochia populations in those crop rotations,” Geddes said.

He added that people should avoid the idea that herbicides are the only tool available to manage weeds.

Beyond increasing the diversity of crops grown in the rotation, there are many other cultural management tools growers can use that help prevent herbicide-tolerant weeds from taking over their fields. However, many of these techniques are far less effective when herbicide resistant weeds are already present.

“The ability for some of these tools to be effective for weed management depends on the density with which resistant weeds are present in the field,” Geddes said.

“One crop rotation study that was led by Breanne Tidemann that we just finished showed that once the weed seed bank was high enough, a lot of these cultural lead management tools were not as effective anymore.”

Geddes is involved in multiple studies that examine how cultural production techniques can reduce the selection pressure management practices place on weeds.

For instance, something as simple as harrowing the fields shortly after harvest can help wake up weeds, which can greatly reduce the number of weed seeds.

“You’re essentially promoting germination through seed-to-soil contact, and then those seedlings are essentially dying due to the cold weather,” Geddes said. Another study he recently led examined how herbicide layering throughout the rotation combined with two cultural practices, increased seeding rates and narrow row spacing, can affect yield loss due to herbicide-resistant kochia.

“We actually planted glyphosate-resistant kochia into the plots at the beginning of the experiment. And then basically, our challenge is to try and manage the herbicide-resistant weed, using both a chemical management program but then also adding in cultural management to help get an additional edge.”

Auxinic-resistant kochia plants were not planted, however, because kochia is building resistance to that chemistry.

The study used a four-year rotation of wheat, canola, wheat and lentils.

In both wheat crops, a glyphosate pre-plant was used with carfentrazone, and for the in-crop herbicides pinoxaden, pyrasulfotole, and bromoxynil were used.

For the canola rotation ethalfluralin was used the fall before, glyphosate was used pre-plant, and glufosinate and clethodim were used in-crop.

For lentils, glyphosate and saflufenacil and pyroxasulfone were used pre-plant, and imazomox was used in-crop.

Liberty Link canola was used because Geddes said glufosinate has good activity on kochia.

“We had all of these phases present within every year, and then in addition we also have this entire rotation using either wide-row spacing versus narrow spacing, as well as either seeding these crops at the recommended densities versus double the recommended densities.”

He said it was easy to see plots with cultural management of decreased row spacing and increased seeding rates because they had better success competing with the kochia.

In the first two years of the study, 2018 and 2019, crop density did not have an effect but in 2020 crop density had a significant effect with a 74 percent reduction in kochia biomass when a higher seeding rate was used.

“Increasing crop seeding rate is one of the most effective and also consistent methods to increase the ability for your crop to compete with weeds,” Geddes said.

“It’s been shown repeatedly in several different crops across several different geographies that this is a valuable tool that farmers can implement.”

Higher seeding rates add costs but it is likely to pay off in the long run.

“I think that there’s also some utility in looking at using weed populations or population density as a tool to develop some of those precision ag maps to help guide some of these cultural tools.,” said Geddes.

“For example, guiding your seeding rate and maybe making your crop more competitive in areas where there’s higher weed pressure.”

When it comes to row spacing, this practice had a consistent effect throughout each year of the study with glyphosate-resistant kochia.

“Growing the crops with a wide-row spacing versus the narrow spacing, we have about 60 percent reduction in the (kochia) biomass,” Geddes said.

“We’re really seeing better performance of those herbicides, and then also increased competition with the kochia plants that remained unmanaged.”

In 2018, in the plots where herbicide-resistant kochia was present, there was a 26 percent increase in crop yield in all crops and crop rotation phases in the plots with narrow-row spacing.

Brenzil said there is an extra cost to going with narrow row spacing because every run placed in the ground costs energy that requires more fuel and possibly a bigger tractor, but that narrow row spacings have benefits beyond boosting the crops’ ability to compete with weeds.