If seed treatments are marketed as an insurance, should growers buy insurance against a pest they don’t have?

The on-farm-network agronomy program is a dig-in-the-dirt activity of Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers.

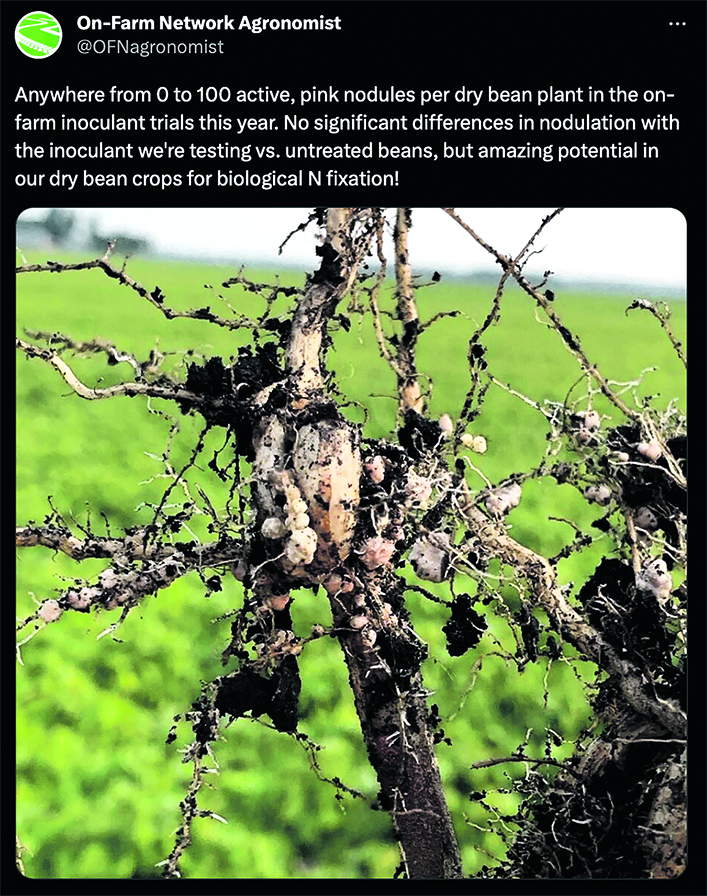

The digging and root checking is performed in pursuit of pink nodules on legume roots. Among other things, a root check can tell the grower whether the seed treatments and inoculants of his choice are working.

For 2023, MPSG is running two pea seed treatment trials, four dry bean inoculants trials, 11 soybean inoculants trials and 13 soybean seeding rate trials.

The MPSG is a non-profit, member-based corporation representing 3,800 farmers who grow pulses: edible beans, peas, lentils, chickpeas, faba beans and soybeans. It tries to advance all phases of the pulse and soybean industry, and is directed and funded by producers. The group has produced 79 videos that summarize results to date and it document results over the length of the trial.

Executive director Daryl Domitruk says one reason for launching the on-farm network was to compare plot-based recommendations to real-world results.

“Since 2013 we’ve done 550 on-farm comparisons. It’s one thing to arrive at a recommendation based on plot research, but what happens when you give that recommendation to a grower? Is it relevant to his field?

“Through the checkoff, we have a pretty good allocation of money earmarked for research, so we fund the universities and Ag Canada stations. A few years ago we decided to put some of that money into farmer’s hands, with the condition they conduct replicated field-scale trials.

“The on-farm-network agronomy program only deals with real-farm practices. It uses the farmers’ own equipment, time, labour, soil and other restraints. Most fields are a quarter section.”

Domitruk says the program is at the far end of the applied research continuum. Researchers determine what’s going on in the soil but when it comes to practical on-farm application of that knowledge, agronomists and farmers need to verify their results.

“Inoculants for example. We’ll take two different types of inoculants, a granular and a peat based. Or seed-coated versus mid-row band. We only set up two or three treatments so it’s do-able.

“We work with the farmer to set the trial up and replicate the treatments in a scientifically rigorous comparison. We help set up the runs and lay out the replications.

“The farmers job is to have the interest and the patience and the time, especially the time, to change the treatments after each run. If you’re doing mid-row banding on one set of strips, then you change the treatment to seed-placed product, well that switch is going to take some time.

“We work with the cooperator to make sure it all happens on schedule. The farmer manages the crop just as he would his normal crop. The idea is to mimic actual farm operations.”

At harvest, the MPSG team is there to record the yield. The data runs through statistical analysis and the farmer gets the results.

Then the data is combined with all the farms that conducted the same trial. The group is careful to set the trial up to measure the efficacy of the product, not the type of drill or performance of the sprayer. And it tries to encompass as many regions and conditions as possible.

Domitruk said treatments to protect the seedling are also a concern for soy and pulse growers. Seed often comes with the protective treatment already applied and incorporated into the cost. He said growers question this extra cost.

“Should a farmer buy treated seed or not? We’ve conducted 70 on-farm trials on chemical seed treatments for fungicides and insecticides. Only 14 percent of those treatments showed a positive response.”

He said seed treatment is often sold on the basis that it’s like insurance, but should growers buy insurance against an insect or disease they don’t have?

Scientists are working to identify indicators of insects or disease in the soil. Once this work is available, growers can make better decisions on seed treatments.

Domitruk notes insurance is only able to prevent yield loss from turning into financial loss and a cold, wet spring might warrant seed treatment.

Zero till is another area of exploration for the grower group. Pulse and soybean varieties have been developed for a prepared seedbed. Domitruk says concerns over soil and water management have many members considering a move away from a highly prepared seedbed. MPSG is starting to explore these possibilities.

Soybean seeding rate is always a big question for growers because seed is costly. The seed company wants robust sales and the farmer doesn’t want to buy more than needed. What is the right rate?

The grower group conducted plot research with Ag Canada years ago to find the right number. It showed that, officially, the population should be about 175,000 plants per acre.

“But is the 175,000 number relevant to the farmer who’s planting across a variable landscape, maybe into different soil conditions, moisture and chemistry,” asked Domitruk.

“To try (to) find that number, we did more than 40 seeding rate trials. We used three seeding rates, a high that’s above the recommendation and a low that’s below the recommendation. And one strip at the recommended rate as a benchmark.

“Our on-farm trials confirmed that the rate should be in the range of 175,000 but you can get away with a little less in many cases and there was no benefit in going higher. When these recommendations come from real farmers in real fields, it carries a lot more credibility, even though the numbers match up with plot numbers.

“This is a big commitment for guys doing the trials. They have to stop what they’re doing at a critical time in the season and change seeding rates three times. Honestly, it is so impressive.”