Crops took some, soil took some and weather took some, but the true measure of what remains is challenging to assess

High levels of residual nutrients might be available in many prairie fields going into the 2022 growing season because of the drought last summer.

Fertilizer expert Rigas Karamanos said inadequate water last summer caused reduced nutrient uptake of applied fertilizer by crops over wide swaths of the prairie provinces.

“There is tremendous amount of residual fertilizer that will be staying in the soil depending, of course, on the management that each of the producer uses,” Karamanos said in a Jan. 12 virtual presentation during Alberta Agronomy Update.

“Dry (conditions) also means that if you were to do a soil test you will realize there is a tremendous variability in the nutrients, especially when it comes to nitrogen.”

He said poor crops do not use up nitrogen and there is little nitrogen mobility in dry conditions, so growers can expect to have nitrogen stranded within the top three inches of the soil where they applied it.

However, he said late summer rain in some regions may greatly change the nutrient status of fields because of crop regrowth.

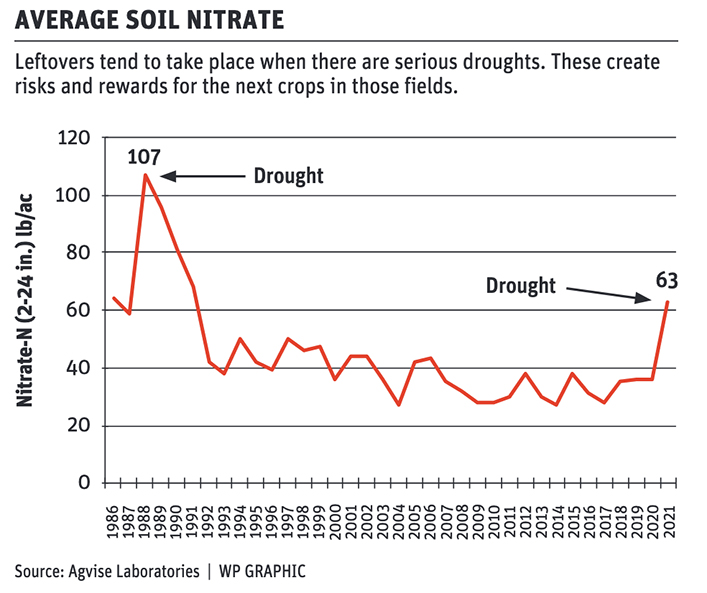

Using data provided by Agvise Laboratories, Karamanos displayed average soil nitrate levels following wheat in Saskatchewan and Manitoba from 1986 to 2021.

Nitrate levels skyrocketed to 107 pounds per acre in 1988 because of drought that year, and they remained higher than average in the three following years.

In 2021, the average soil nitrate levels were 63 lb. per acre, while it was 36 lb. per acre in 2019 and 2020.

Nitrate levels are not the only soil property significantly affected by dry conditions.

“When you have a drought, there is a decrease in the soil pH and that decrease is also followed by an increase in the electrical conductivity or the salts. They are more concentrated,” Karamanos said.

Phosphorus levels in the soil can also come up in dry times and growers must be careful because these elevated levels are temporary.

“If you sampled last fall, as an example, your phosphorus could be very high, and we got some moisture in some parts of the province and that can change things for spring. So, you know, be very careful of these changes,” Karamanos said.

Soil sampling regimes may need to be modified because dry conditions can increase the variability of the nutrient levels throughout the field.

For instance, it’s important to take special care when extracting cores of dry soil because it’s easy to lose power-dry soil from the bottom of the core.

“You put that probe down to one foot but it’s so dry that say you lose three inches. Say there were 20 parts per million in the top and six parts per million the bottom six inches. But if you lose three inches, now you’ve got nine inches and you have 26 parts per million,” Karamanos said.

“Your recommendations are going to be much lower than what they should have been.”

Samples can also be taken from areas that have excessive nutrients, such as the furrow, and they are not a good representative sample of the field.

Therefore, Karamanos suggests growers take the results of soil testing after dry years with a grain of salt.

“The philosophy of soil testing, we have sufficiency, we have maintenance. Well, when the prices are the way they are, maybe you should start thinking about sufficiency and leave the maintenance alone,” Karamanos said.

For fields that are particularly dry at planting, he said it may make sense for growers to use a split application of nitrogen with a top dress, band or foliar-applied product.

If it stays dry less fertilizer will have been applied up front that will not be used up this year, while if the region does receive enough rain to grow a crop growers can then decide to apply the rest of their crop’s nitrogen requirements.

“In order to get the maximum yield for wheat or cereals you have to apply prior to the first node being visible. If you apply later, you’re still going to get a yield increase, but not the maximum yield,” Karamanos said.

“The maximum rate with which nitrogen is taken up by canola is at the six-leaf stage… That occurs about five or six weeks after seeding. So, you have to have the maximum nitrogen rate on prior to the six-leaf stage in order to get the maximum yield.”

He also cautioned that split nitrogen applications can be uneconomical because of extra cost of application and damage to standing crop.