Barry Hall has fielded one question more than any other surrounding the genetically modified flax incident.

“Who’s going to pay for this?” said the president of the Flax Council of Canada.

Flax trade with Europe ceased in September when European labs detected a long deregistered GM flax variety called CDC Triffid in food products.

Canadian grain industry and government officials are still attempting to confirm whether Triffid made it into the handling system.

Read Also

Trade war may create Canadian economic opportunities

Canada’s current tariff woes could open chances for long-term economic growth and a stronger Canadian economy, consultant says — It’s happened before.

But one thing is clear – the mere mention of it has shut down trade with a market that bought $317 million of the oilseed in 2008.

No one can pinpoint how much the incident has cost the Canadian flax industry, but a European flax buyer said it has cost processors millions of dollars in lost revenue.

If it turns out that an individual farmer or a group of farmers knowingly grew Triffid, there are those who want them taken to task.

But Hall said it’s not that simple.

“I keep coming back to the same point,” he said.

“It is not illegal to grow a (deregistered) variety in this country.”

If a farmer knowingly grew and delivered Triffid into the system, he might have done something morally wrong but as long as he didn’t misrepresent what he was delivering, he didn’t break any laws. Hall believes it is unlikely any misrepresentation occurred.

“Up until this time, who ever asked about flax?” he said.

But there may come a time in the not-too-distant future when flax growers are asked to declare what they are delivering, similar to what wheat producers were asked to do starting in 2008-09.

“It’s something that I think is being seriously looked at by some of the companies,” Hall said.

The wheat industry brought in the producer declaration system to replace kernel visual distinguishability (KVD), which was preventing registration of some general purpose wheat varieties.

Wheat industry officials and government regulators say that aside from a few minor blips, the new system had a smooth launch, and most growers have embraced it.

But there are some who believe the industry is going down the wrong road by implementing a mechanism that allows grain companies to go after farmers who purposely or accidentally misrepresent what they are delivering.

While contamination of the grain system with ineligible varieties is rare, it can be costly.

In 2002, 5,000 tonnes of No. 1 Canadian western red spring wheat shipped from an Agricore United elevator at Canora, Sask., was downgraded to feed after 60 rail cars arriving at export terminals in Thunder Bay, Ont., and Montreal were found to be contaminated by an unlicensed U.S. hard spring wheat variety called Oxen.

One year later, a 938 tonne cargo of Saskatchewan Wheat Pool wheat that was given a final certified grade of No. 2 CWRS was later downgraded to feed by the Canadian Grain Commission because unregistered varieties made up 20 percent of the samples it had retained and analyzed. The downgrade cost Sask Pool $48,000.

Norm Woodbeck, the grain commission’s acting chief inspector, said he has been with the agency since 1975 and every year there is some type of contamination incident.

“In some cases we’ve realized it’s just lack of communication on our part. The individuals didn’t even realize that what they were growing was not eligible,” he said.

For example, farmers delivered 28,000 to 30,000 tonnes of Pelissier durum into the handling system in 2008-09. The problem: it was deregistered more than two years ago when the breeder no longer wanted to maintain the seed.

Lawrence Klusa, the Canadian Wheat Board’s quality control manager, said ineligible varieties can cause serious harm to Canada’s reputation as a consistent supplier of quality wheat.

He said buyers pay for varieties that go through extensive testing and development and don’t want to see wheat with substandard milling and baking qualities in their orders.

The grain commission wouldn’t provide data about how often contamination incidents occur in its monitoring program because that is considered commercially sensitive information.

“I wouldn’t say that it’s widespread, but there is presence there,” said commission spokesperson Rémi Gosselin.

“We consider it to be under control. You’re talking about low level presence.”

Wade Sobkowich, executive director of the Western Grain Elevator Association, said the commission provides the grain industry with monthly reports, and every month there are cases of ineligible varieties detected in the system. Although they are often within accepted tolerance levels, the mere presence of those varieties means the potential for a costly incident. And those cases could be on the rise.

“I believe it will come up more and more as new varieties get registered that no longer have to meet the KVD requirements,” he said.

Klusa agreed. When some of the new general purpose wheat varieties reach the market, it may be hard to distinguish them from other classes of wheat, which means producers will have to be extra vigilant to ensure they aren’t blended with one another.

“It will become more of an issue as we move forward,” he said.

The producer declaration system was a pre-emptive measure to nip that in the bud.

Michael Halyk, a farmer from Melville, Sask., and former wheat board director who is a long-time opponent of the declaration system, would prefer policing be left to the grain commission.

“We need some teeth in the (Canada) Grain Act so that the grain commission can actually rule with an iron fist, because they can’t,” he said.

Bill C-13, which was introduced in Parliament to amend the Canada Grain Act, would have given the grain commission the ability to fine or penalize farmers for misrepresenting what they deliver, but it isn’t expected to be passed.

That doesn’t mean farmers are off the hook. Grain companies looking to recoup their losses can and have taken them to court. So while there are no regulatory penalties, there can be substantial civil liability under the new system.

“It’s like no speeding tickets but if you get into a crash, God help you,” Sobkowich said.

Along with the producer declaration system came a trace-back protocol designed to indentify who is responsible when wheat and durum supplies are contaminated with ineligible varieties.

The grain commission samples an unspecified number of rail cars unloading at export terminals and vessels bound for export markets. It will contact the grain shipper if it detects an amount of ineligible varieties exceeding its tolerance levels.

The grain company then works with the wheat board and the end use customer to mitigate damages associated with the contamination by blending the grain or finding a market that will accept it.

If there is residual damage, they use the protocol to trace the grain back to the samples collected and stored at the local elevator.

The grain company is on the hook for damages if it can’t show which farmer or farmers misrepresented their wheat.

If it can finger the culprits, the wheat board’s pool accounts are debited, and it is then up to the grain company and the board to decide whether to sue the growers for negligence or fraud.

“Either all farmers are going to take the hit through the pool accounts or the decision will be made to go after those specific farmers so all farmers don’t have to share in that liability,” Sobkowich said.

The liability can be substantial. A single contaminated elevator could cost as much as $400,000, he said. Downgrading the grain in the hold of a ship’s vessel to feed could cost $1 million.

Klusa can’t recall any contamination incident where the damage reached those lofty levels.

“It could potentially get into the hundreds of thousands (of dollars), but I haven’t seen anything like that.”

Halyk said producers don’t fully understand the declaration they sign at the local grain elevator and are ill prepared for the consequences if things go awry.

“Very few farmers carry liability insurance to cover something like that, so in most cases it could bankrupt the farmer if that were to occur to him.”

National Farmers Union vice-president Terry Boehm said he misses the days when farmers and their grain co-operatives worked together to resolve such problems.

“Now it appears to be designed to almost become an adversarial system, which I think is unfortunate.”

He said he can understand why grain companies want to punish growers who knowingly undermine the industry, but what about those who simply goofed?

Sobkowich said it doesn’t matter to the grain industry whether the contamination is accidental or intentional because the damage is the same either way.

“If somebody does it on purpose, it’s fraudulent,” he said.

“If somebody does it by accident, it’s negligent. But it’s still a big problem.”

Industry representatives interviewed for this story can recall only one time when a grain company sued a farmer for misrepresentation, and the details were too scant for publication.

However, Sobkowich expects it will become a more common occurrence under the declaration system if farmers don’t practice due diligence.

He knows of one contamination case since declarations were put in place, but the grain companies involved didn’t follow the protocol as closely as they should have and were unable to trace it back to the producer. As a result, they had to absorb the damages. Those companies have since upgraded their protocol procedure.

Boehm doesn’t like the litigious approach. He believes grain companies already factor risk into the price and basis they offer to growers.

“Farmers are paying for these problems incrementally on a relatively large scale,” he said.

Boehm believes a distinction needs to be made between delivering a crop such as Pelissier durum, which had minimal market consequences, and the planting of a deregistered GM crop that can destroy an entire premium market.

“That’s a whole different ball of wax,” he said.

He said he also believes the likely result of the GM flax incident will be an increased requirement for farmers to plant certified seed.

He would consider that a disastrous consequence because he believes the lack of saved seed competition in the canola industry, which is dominated by hybrid seed, is one reason seed costs $550 per bag.

“That is absolutely outlandish. It’s shocking,” he said.

He would like to see more extensive advertising and communication when a variety is deregistered and a public appeals process that allows farmers to make an argument for keeping the variety registered.

The grain commission has a new initiative that will partially address his concerns. It will be widely publicizing new deregistrations three years before they take effect, giving the grain industry and farmers a heads up of what’s coming.

“It’s just to give an early warning so that, come the specified date, a producer is not sitting there with four bins of variety X and suddenly, instead of being eligible for No. 1, it’s only eligible for feed grade,” Woodbeck said.

The commission is also attempting to develop a rapid and affordable technology to identify unwanted varieties, which would provide a more guaranteed way than the existing honour system for identifying what is being delivered into the system.

“It’s still in development, but we’re still a few years away before even thinking of implementation at this point,” Gosselin said.

Klusa said private companies are also working on perfecting the technology. He said it would most likely augment the existing producer declaration system unless the companies develop an inexpensive “driveway test.” Then the grain industry could talk about eliminating the producer declaration system.

In the meantime, the onus is on producers to check the commission’s website to stay up-to-date on which varieties are registered for each class of wheat.

“A lot of it comes back to grain producers,” Gosselin said.

“They play a key role in maintaining Canada’s reputation for high quality, dependable grains.”

Glossary

* Deregistered varieties are those that were once registered in Canada but had that registration withdrawn. * Unregistered varieties are typically ones from the United States that never received registration in Canada. * Ineligible varieties capture all of the above, plus registered varieties that are delivered to the wrong class of wheat.

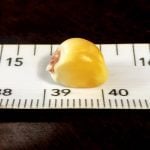

Designated flax varieties

The Canadian Grain commission designates the following varieties of flaxseed as Canada Western as of July 31, 2009:AC CarnduffAC EmersonAC LinoraAC McDuffAC WatsonCDC ArrasCDC BethuneCDC MonsCDC NormandyCDC SorrelCDC ValourFlandersHanleyLightningMacbethMcGregorNorLinNorManPrairie BluePrairie GrandePrairie ThunderShapeSommeTaurusVimy50**contract registered

Web links

* The Canadian Food Inspection Agency has a list of registered varieties in Canada. Go to the plants page under “variety registration” at www.inspection.gc.ca/* The Canadian Grain Commission has a list of registered varieties of wheat and flax at www.grainscanada.gc.ca* The Canola Council of Canada maintains information about varieties and herbicides that should not be used at www.canola-council.org/export_ready.aspx

The producer declaration form

On Aug. 1, 2008, a declaration system was introduced as part of a quality management system for western Canadian wheat.At the beginning of the crop year, producers must complete and sign the form, declaring the wheat they deliver now and for the rest of the year is from “eligible varieties for delivery for the class of wheat for which payment is being requested … .”If an ineligible variety is represented to be eligible, the grain company or the Canadian Wheat Board may consider the representation to have been made “fraudulently and/or negligently.” The producer agrees “that the Canadian Wheat Board may consider the producer to be in default of his/her delivery contracts and, in addition to any other remedies available to it, it may cancel any contracts of the producer.”The grain company and the CWB may also hold the producer liable “for all claims, damages, losses and costs (including legal fees) that may result.”