Glacier FarmMedia – Finding additives to supplement peat moss could make horticultural produce more sustainable and ensure that peat is available to use for many years, according to a professor and researcher at Assiniboine College in Brandon.

“You don’t want to harvest it as a one-time media and throw it in the garbage,” said Poonam Singh of the college’s Russ Edwards School of Agriculture and Environment.

Singh noted that around 59,000 acres of peatland have been drained for use in Canadian horticulture, with almost 35,000 under active extraction. Canada is now one of the largest global peat producers, sourcing the material from sphagnum moss.

Read Also

Alberta cracks down on trucking industry

Alberta transportation industry receives numerous sanctions and suspensions after crackdown investigation resulting from numerous bridge strikes and concerned calls and letters from concerned citizens

According to the Canadian Sphagnum Peat Moss Association, peat forms through the gradual accumulation of plant material that has undergone incomplete decomposition in waterlogged, oxygen-poor and acidic wetland environments.

It has a lot going for it as an agricultural product. Peat moss’s high water-holding capacity, natural structure and lack of pathogens make it popular as a growth medium for ornamental and food production in controlled environments.

The material’s ability to absorb and hold 12 to 20 times its dry weight in water makes it valuable for managing moisture.

Its capacity to enhance the soil’s ability to hold and gradually release nutrients while reducing fertilizer runoff is praised for nutrient management.

Additionally, peat provides aeration through natural air spaces that encourage strong root growth and plant development. It doesn’t compact through the growing cycle, maintains low electrical conductivity and has a pH that supports plant health.

However, it doesn’t restore itself quickly, and the process of harvesting often turns odds against renewed sphagnum moss growth after the site is depleted.

“At one time, it used to take 40 years … to bring (peatland) back to its original biodiversity level,” Singh said.

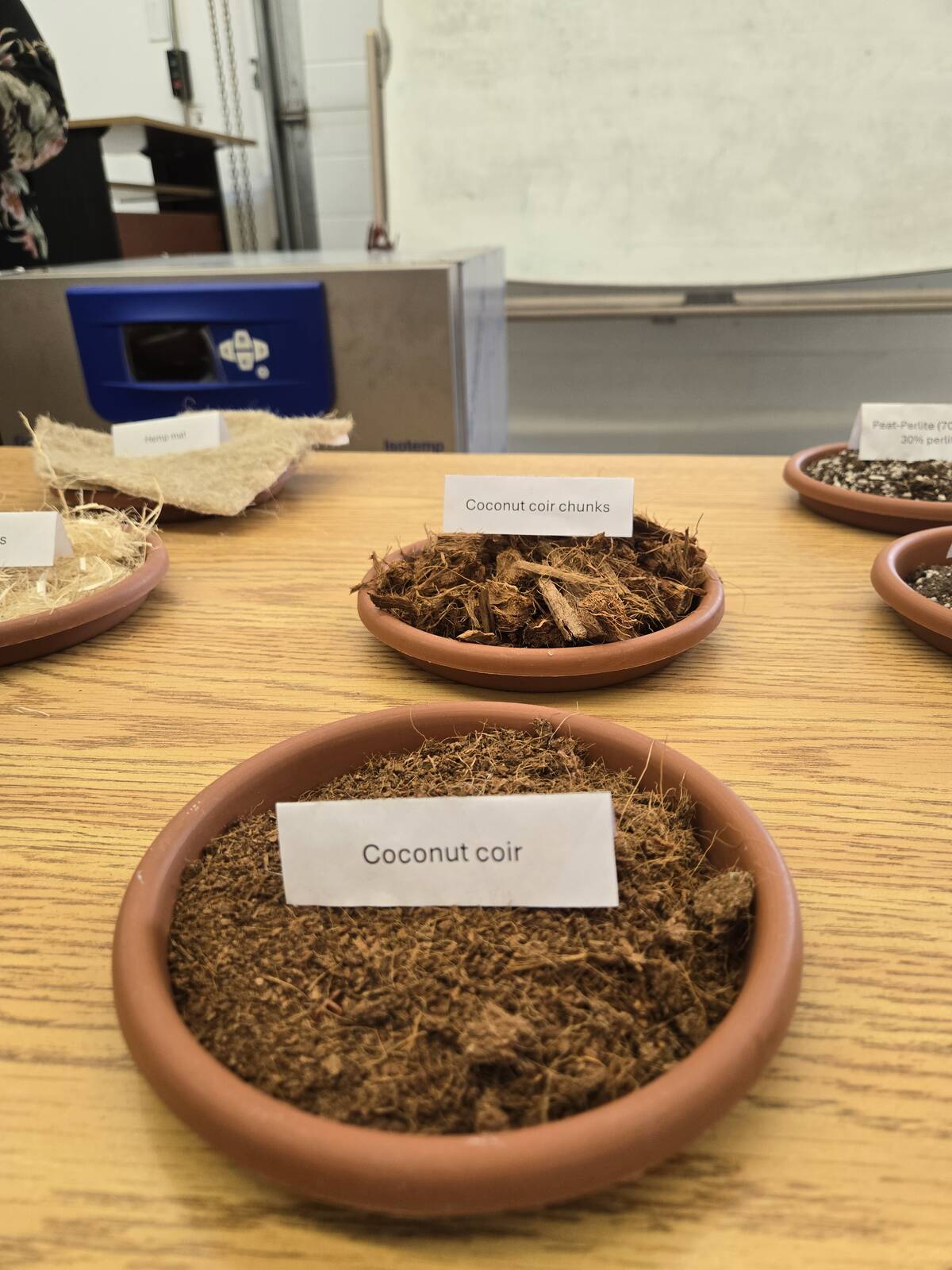

Researchers such as Singh are instead looking for things they can add to make harvested peat go further, including compost, coconut coir or biochar, wool fibre, cattails, wood products and insect frass and worm castings.

They’re testing how much of the peat they can substitute and which kinds of peat extenders they can blend in while maintaining peat’s effectiveness as a growth medium.

Replacing peat with even 10 to 20 per cent alternative growing media can positively impact the industry, Singh said.

“There are so many other materials that have potential.”

In particular, the research is looking at materials that are byproducts or would otherwise be wasted from other sectors.

“If there is a waste product of one industry that can be used as a growing media, what could be better than that?” Singh said.

Those substances have a high bar to clear, however. Peat is a versatile, highly mixable substance due to its structure, predictable performance and low disease risk, researchers said. This allows for specific mixes tailored to particular crops or growing conditions.

Singh’s research suggests that at least some substitution is possible without giving ground on plant health and growth. In one 2024 study using cattails, mixing the additive in low levels (between 10 and 20 per cent) supported comparable plant growth. Plant size, chlorophyll content, leaf development and root growth were all measured.

Much higher than that, though, and plant growth started to slow. Singh believes that was caused by nitrogen immobilization due to microbial activity.

Currently, Singh and her team are looking at how composted cattail fibres affect the nitrogen immobilization that raw fibres caused in the first trial. She hopes that will let them increase the proportion of cattails in the mix.