WINNIPEG — The story of the 2024 canola crop can be summed up with three brief phrases:

Hopes for a bumper crop in late June.

Blazing heat and minimal rain in July.

Read Also

Mail strike disrupts grain sample delivery

The Canadian Grain Commission has asked farmers to consider delivering harvest samples directly to CGC offices, services centres or approved drop offs as Canada Post strike delays mail.

Disappointing yields in September.

Those are the Coles Notes, but the agronomic story is slightly more complicated.

A long stretch of 33 C heat this summer and lack of rain was a massive drag on yield. However, in many parts of the Prairies, the agronomic problems may have started in June.

“We had six inches (150 millimetres) of moisture from May 1 until the end of June. Every week we were getting almost an inch (25 mm) of rain. This is specific to our geography, but a lot of south Saskatchewan would be in the same position,” said Travis Wiens, an agronomist with MNP in Milestone, Sask., south of Regina.

The consequence of the consistent spring rains was that canola plants didn’t have to hunt for moisture, Wiens said.

“What we ended up with was a crop that wasn’t rooted as well as it has been the last couple of years.”

Wiens shared data supporting the idea that canola roots were relatively shallow in 2024.

“Looking at our John Deere moisture probes … and Crop Intelligence moisture probes, we historically will pull from 80 to 100 centimetres. Crop roots will get down to that depth by early July,” he said.

“This year we had lots of probes that never pulled from more than 60 to 70 cm.”

So, when the rain stopped in the first week of July and summer heat arrived on the Prairies, canola plants weren’t prepared.

Weather data from Milestone indicates that parts of Saskatchewan received only 25 to 30 mm of rain in July.

The crop didn’t have the necessary roots to find moisture and nutrients in the deeper layers of soil. That partially explains why canola yields were average or below average on many farms, despite ample moisture in the spring and robust crop stands in early July.

In mid-September, Statistics Canada pegged the average canola yield in Western Canada at 38.4 bushels per acre. That number is very similar to 2022 and 2023, when the average yield was 39.1 and 38.7 bu. per acre, respectively.

South of Regina, some growers recorded yields in the 20s or less.

“South of Highway 13, there was lots of canola that was under 20 bu., which is even worse than last year,” Wiens said.

Ian Epp, a Canola Council of Canada agronomist in Saskatchewan, agreed that shallow and smaller roots contributed to frustrating yields in 2024. If the crop is well-rooted, it can tap into moisture and “mitigate” a period of heat stress.

However, canola plants also need nutrients to combat stress. There may have been a shortfall of critical nutrients at flowering and after the bloom period.

“We saw some sulphur deficiency, some nitrogen deficiency,” Epp said.

“Some of those nutrients, especially the sulphur … it may have been available, but it was far deeper in the root profile.”

June rain may have washed the sulphur downward in the soil, and roots weren’t able to access the nutrient.

Agriculture Canada scientists in Saskatoon have found that adequate sulphur fertility can help canola tolerate “water deficit conditions,” says the council website.

“That could be another reason why we saw canola get hammered a little bit harder than other previous years, when sulphur was more available,” Epp added.

Potassium isn’t typically an issue for canola growers because the young soil of Western Canada provides sufficient supplies of the nutrient, says the council website.

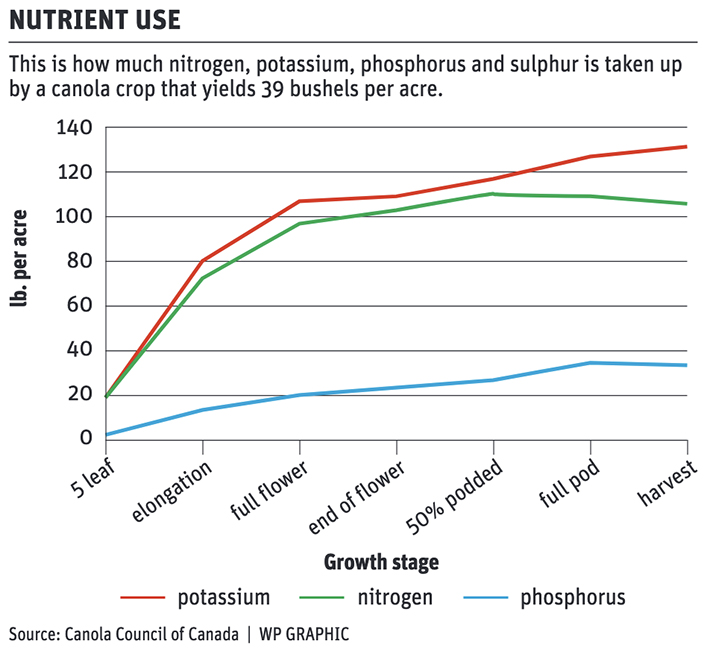

At the same time, the canola council has a chart showing that canola requires a significant amount of potassium oxide.

“Not one day in its life does canola need less potash than nitrogen,” Wiens said.

“Every day it needs more potash than nitrogen.”

If testing shows that soil contains less than 250 pounds per acre of potash, canola may need an application of potassium, the council says.

“Potash is an interesting nutrient,” Wiens said.

“It helps control water regulation in a plant. So, if we were short potash in these fields, you would absolutely see that plant suffer a little bit more from drought.”

Looking beyond nutrients, diseases such as sclerotinia and verticillium stripe may have also robbed growers of a few bushels this year.

In the spring and early summer, 2024 was shaping up as a nasty growing season for sclerotinia because of the excess moisture in June and the density of the canola crop on many fields.

It didn’t turn out that way.

“There was some sclerotinia around … (but) it wasn’t the huge sclerotinia year it could have been,” Epp said.

“Not near what we would of expected … because we stayed so hot and dry.”

As for verticillium, the soil-borne disease is now entrenched in Manitoba and is spreading westward. Wiens has heard reports of it being detected in North Battleford, Sask.

Nonetheless, what verticillium means for canola yields in Saskatchewan isn’t well understood, Epp noted.

Smaller and shallow roots, a shortfall of nutrients and disease pressure all played a part in mediocre yields this growing season.

However, the big story is the same — hot and dry conditions in July and early August, during bloom, pod formation and pod fill, resulted in fewer pods on canola plants, fewer seeds in the pod and smaller seeds.

Ultimately, summer weather dictated canola yields in 2024.

“Mother Nature bats last,” Wiens said.