A former American slave who became an Alberta icon because of his skills as a cowboy and rancher helped inspire a black filmmaker to understand her own place in the real history of Western Canada.

“It was very confusing for me as a child to be aware that black roots in the country were long and deep, and yet not to have any recognition of that outside of my own circles,” Cheryl Foggo said about her fascination with the life of John Ware.

Related stories:

- New documentary focuses on black settlers

- Racism not someone else’s problem

- Racis an old issue with sad history

Foggo is descended from pioneers from Oklahoma who helped settle black prairie communities such as Maidstone, Sask.

“But it was as though at school, every black person had arrived yesterday. And I think for most Canadians, they don’t think of blackness as something that is from the Prairies, and in fact it is.”

Her documentary, John Ware Reclaimed, is being shown online for free during Black History Month as part of Perspectives from the Prairies, a year-long series of films launched in 2023 by the National Film Board of Canada and The Western Producer to celebrate the newspaper’s 100th anniversary.

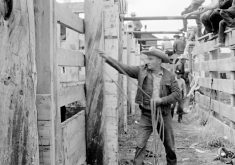

Ware, who lived from around 1850 to 1905, was designated a person of national historic significance by the federal government in 2022. A plaque in his honour was unveiled at the Bar U Ranch National Historic Site near Longview, Alta., where he worked as a cowboy in the 1880s.

“John is not only one of the best natured and most obliging fellows in the country, but he is one of the shrewdest cow men, and the man is considered pretty lucky who has him to look after his interest,” said the Macleod Gazette in 1885.

“The horse is not running on the prairie which John cannot ride.”

Foggo was honoured as a member of the Alberta Order of Excellence for her work as an award-winning documentary filmmaker, playwright, author and screenwriter of the TV show, North of 60. She grew up in the 1950s and 1960s in what is now the Calgary neighbourhood of Bowness.

Although Ware was buried in the city, she knew little about him as a child.

“We had a vague notion of a cowboy named John Ware, but we didn’t know he was black.”

Foggo grew up loving horses as well as cowboy stories in TV shows and movies, which were a strong part of her identity. However, she began to think that black people like herself didn’t belong in what was presented as a white-dominated world.

Learning about Ware helped her embrace her own history as a black western Canadian.

“Ultimately, it allowed me to be comfortable with many different aspects of my identity, including that I am from the West.”

Ware overcame being enslaved in the American South to become a cowboy and rancher after the Civil War in an era when Western Canada’s white-dominated ranching industry was largely controlled by well-financed corporations, said a federal statement.

He started his own ranch in the Millarville area near Calgary before moving to a site near Brooks, Alta.

“And he was obviously not just smart, but also savvy,” said Foggo.

“From what I can gather, he was very funny. There are stories that are attributed to him of things that he said, and if those stories can be believed, he was very funny.

“He was just so talented as a horse person. He was very talented, he was strong. I mean, he was … truly an outstanding person. He’s just got such a presence — even in the photos, you can see it — and he is a big, strong guy, he’s handsome, and he not just survived, but thrived after what he must have gone through as a younger person.”

As someone whose own ancestors were enslaved, Foggo has read hundreds of accounts of people who lived through the horrors of that experience.

“It was really awful, and it’s amazing that people survived it at all,” she said about Ware.

“And he just seemed so determined to be a full person, and I admire that so much not to let the world take away his one sweet life. We only get one, and he was so determined that it was going to be a sweet one.”

NFB collection curator Camilo Martin-Florez found the information in John Ware Reclaimed to be astonishing, especially for Canadians like himself who live outside Alberta.

“So, when I watched the film, I thought, ‘if creeks, hills, buildings, trails and stamps have been named to honour John Ware, how come I have not heard before about this fantastic guy?’ ”

The documentary, which was released in 2020, re-examines the mythology surrounding Ware as a lone black cowboy and rancher in southern Alberta in light of the fact there were also other black cowboys. It uncovers what is known about the life of an iconic figure and his legacy in terms of the racism that has affected black people both past and present in Western Canada, said Martin-Florez.

Foggo said in the film she wanted Ware to be more than a prop in a happy story Canada tells itself about itself. The Dictionary of Canadian Biography notes that he was also known as N—– John, and his children fought as adults to get the racial slur removed from geographical locations named after their father.

The documentary underlines how Ware found the epithet to be demeaning despite claims to the contrary, at one point taking matters into his own hands after a bartender called him the N-word and refused to serve him. Ware’s son found it difficult to find work due to his race.

Foggo said it is baffling that many Canadians believe there isn’t any anti-black racism in this country or that they describe it as not as bad as the United States. Any amount of racism is “unacceptable and horrible, and all its different forms are bad.”

The name calling that led Foggo to be afraid to go outside her neighbourhood as a child is part of a larger history of racism in Western Canada, she said. One of the films she directed is Kicking Up a Fuss: The Charles Daniels Story, which is about a black man who was refused access in 1914 to a ticketed seat on the main floor of a Calgary theatre due to his race.

He took the theatre’s management to court in one of Alberta’s first civil rights cases. It predated by decades the similar case in 1946 of Viola Desmond in Nova Scotia, who is today remembered on Canada’s $10 banknote.

Foggo said the trickle of immigration by black Americans that started about 1905 was shut down by Canada’s immigration officials about 1912. It is one of the reasons why there weren’t further waves of black pioneers like other groups in the Prairies, she said.

“They had hopes of creating bigger communities and really having an opportunity to prove our worth as citizens, and it was very disappointing when that kind of racism that prevented people from coming over happened.”

Visit nfb.ca/channels/perspectives-from-the-prairies/ to watch John Ware Reclaimed.

This column is part of a year-long collaboration between The Western Producer and the National Film Board of Canada celebrating the newspaper’s 100th anniversary.