Before spending money on concrete, steel and pipe, a group urges users to look at the services nature provides

Farmers own, control and are affected by more of the land subject to water issues than anybody else on the Canadian Prairies.

But other than local municipalities, water conservation authorities and charitable organizations, farmers seldom find other players trying to improve water challenges or create regional approaches.

With most water falling on agricultural and wilderness land, the chronic neglect of natural management approaches to water issues exacerbates upstream and downstream water problems in Western Canada.

That’s something the International Institute for Sustainable Development wants to see change. It hopes bigger and better-funded authorities like provincial and federal governments embrace the opportunities of “natural infrastructure” rather than always looking to concrete and steel.

Read Also

University of Saskatchewan experts helping ‘herders’ in Mongolia

The Canadian government and the University of Saskatchewan are part of a $10 million project trying to help Mongolian farmers modernize their practices.

“We used to think of pipes and dams and grey systems as the go-to solutions, and now we’re making the case that nature can play a stronger role in meeting what we need on the Prairies, and they actually provide on occasion a much more cost-effective alternative or complement,” said Dimple Roy of the Winnipeg-based IISD.

Rather than suffering droughts or floods upstream and allowing problems to develop downstream, better management of the water issues that affect farmland, Indigenous communities and wilderness areas would help both the upstream and downstream residents.

For farmers, mitigating drought and flood risks with better water retention and management that relies on natural systems would bring a lot of benefit.

“It is the most powerful when they see benefits to their own productivity, to their own needs,” said Roy about farmers.

“In many cases, the same practices that give us the public benefits, like cleaner water or improved flood risk reduction… helps the people downstream but it’s also often an important benefit for the landowner as well.”

To IISD, “natural infrastructure” involves preserved unchanged natural systems like wetlands and sloughs that hold and gradually release water, restoring natural systems like degraded wetlands and riverbanks, and constructed systems that employ natural concepts to retain and release water non-mechanically.

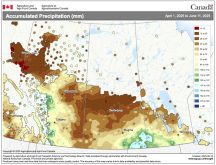

Western Canada is more intensely affected by water issues than almost anywhere else, with extremes of weather, of drought and flood cycles, and of short but dramatic seasonal shifts. It also has a vast amount of farmland and wilderness territory.

The region contains hundreds of water management projects already, with natural systems progressively embraced and developed by programs like those run by Alberta and Manitoba watershed organizations, as well as government-funded programs like Manitoba’s Growing Opportunities in Watersheds, and the federal government’s Living Labs program.

However, those programs are only a pittance compared to the need for improved water management and the degradation of existing systems, with a 21 percent shortfall leading to greater problems.

The IISD report, entitled The State of Play Report for Natural Infrastructure on the Canadian Prairies, praises several existing projects, like the Olds College Floating Treatment Wetlands, which could help small municipalities manage wastewater without a lot of concrete and mechanics.

And it lauds the organizations in Alberta and Manitoba that are well down the road of developing natural systems solutions rather than immediately turning to “gray” answers.

But two major holes exist. One is with Saskatchewan, which has much of the land but less advanced organizations and policies.

However, IISD favours a regional approach to Western Canada rather than a provincial focus, so the experiences in Alberta and Manitoba can help Saskatchewan.

“Where we hope to make a difference is to connect the dots, learn from the best practices, learn the barriers that are really keeping us from taking natural infrastructure to the next level,” said Roy.

“Saskatchewan is where there will be more effort required, but that’s where we can connect the dots and see if there are lessons.”

Still, sharing experiences won’t be enough to significantly develop natural systems for large areas without bigger players involved, ones with real money, such as the provincial and federal governments, IISD says.

Municipalities and other organizations that undertake water management planning need to be convinced to incorporate natural infrastructure into their thinking, and not immediately jump to grey solutions. Often, natural systems can be improved or created more cheaply than new grey systems. Having higher levels of government provide analysis and information about options would help.

Funding will also be important to bring about bigger projects that will have the biggest downstream impacts, IISD said.