Canada learned a lesson about being world class at this year’s soccer World Cup in Qatar.

We aren’t it. Not yet.

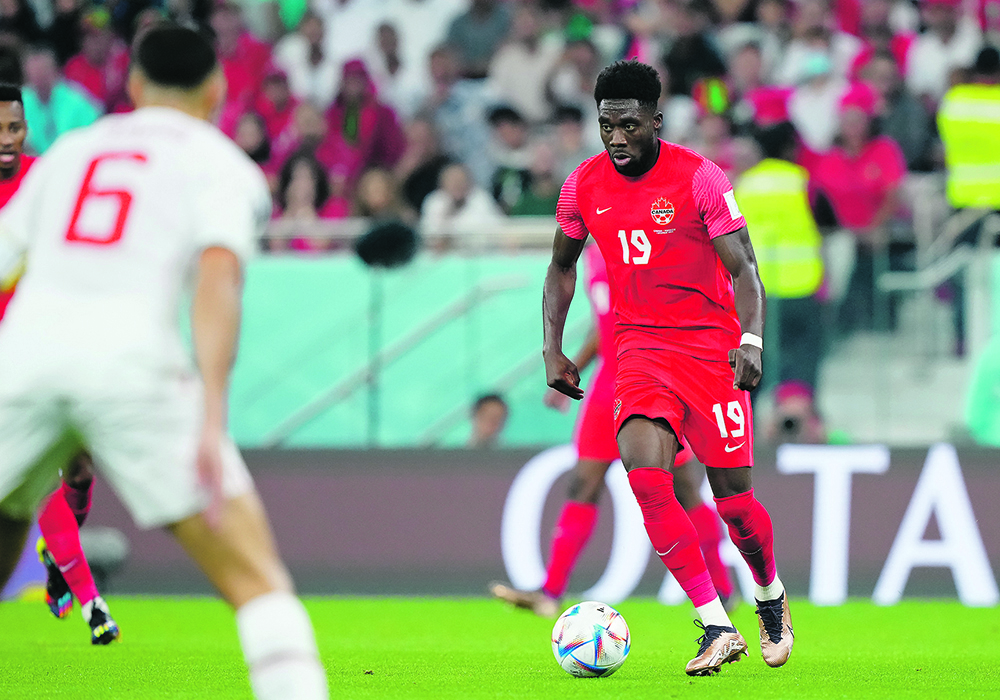

That became apparent after three matches in which the Canadian players showed much energy, determination and courage, but not much else. A poor Belgium side beat us because we couldn’t score. When our boys got tired in the Croatia match, the Croatians ate us alive. Morocco easily outclassed us, despite a valiant effort in the second half.

But the lessons learned will be invaluable for 2026, the World Cup in which we are co-hosts and automatically qualify. Playing against the world’s best players, with a higher level of intensity and scrutiny from fans, commentators and social media trolls, has given Canada’s soccer establishment, players, coaches and supporters many lessons on what it will require to truly compete at a world class level.

Read Also

Pakistan reopens its doors to Canadian canola

Pakistan reopens its doors to Canadian canola after a three-year hiatus.

That’s something about which western Canadian farmers could provide advice because they have been doing it for a century. Canada’s agriculture has been a world competitive industry since the early pioneer days, after tiny local markets for food and feed were saturated.

Western Canada’s grain farming developed along with the transportation and logistics — railroads and ports — that immediately created an export channel that fed hungry European masses.

That provided ready markets, but also stiff competition from around the globe and across Europe, because Canadian crops had to fight for sales. World prices were quickly fed back into farmgate prices, which after being backed off by enormous transportation charges, didn’t provide a margin that allowed any farmer to have a comfortable life.

The wars and the Canadian Wheat Board sometimes obscured the reality of the world market, but Canadian farmers outside of supply management have always been directly connected to world prices and demand. Many harsh lessons have been taught and learned.

This isn’t necessarily true for some of our competitors, in which government programs play a far larger part in farmer economics.

Until recent years, European Union farmers likely spent as much time considering program impacts as they did market conditions and agronomics.

American subsidies and crop-preferring programs have often skewed U.S. acreage and helped create the much smaller hand of crop choices American farmers can play.

It’s been a hard and remorseless history for farmers to endure, but today’s western Canadian farmers are some of the best on the planet.

Any who can’t hit global standards of production haven’t been able to survive. Those who can’t handle the intensity, the yearly stress of weather uncertainty, and the endless financial risks have long since hung up their boots.

Not everybody can be world class, and few want to commit their lives to being so, as prairie farmers must be.

That’s something Canada’s national soccer establishment needs to learn from this world cup: to do better next time, our players need to be playing at world class clubs outside of North America, where standards are higher, intensity is more extreme and there are few excuses for mediocrity. Only two of Canada’s players play at clubs in the world’s top five leagues. Morocco had 15. You could tell.

The pages of this newspaper are filled with stories from around the globe. Winnipeg friends often seem bemused when they ask me what sort of stuff I’m writing about these days, and I tell them it’s issues like international trade, animal diseases overseas and the impact of the war in Ukraine. They assume prairie farmers are growing a bit of wheat, raising a few chickens and making a weekly trip to the local farmers market.

I annoy them by pointing out that our farmers are world class producers of top quality global commodities, fighting for sales with the toughest competitors in the world, and that most of the rest of us are mediocrities doing our jobs well enough for our local communities, but we might not do so well if we had to compete with the best on the planet.

Lots of Canadians got to see how our best soccer players match up against the world’s best during our short stay at the world cup. It’d be great for us to last longer next time.

But for that we’ll need to get our players up to world class standards, and as farmers know, you don’t get that from playing against local competitors. Getting up to world class standards means getting out into the world, as intimidating and humbling as that can be.