A recent study from Ontario’s University of Guelph has found nearly one-third of farmers have had thoughts of suicide in the last 12 months.

The startling numbers are more than two times higher than the general Canadian population.

Dr. Andria Jones-Bitton, along with postdoctorate research associate Dr. Briana Hagen and master’s candidate student Rochelle Thompson, conducted the survey between February and May 2021.

Looking for help now? Check out the Do More Ag Foundation’s support page here.

In 2016 Jones-Bitton and team conducted a similar survey but suicide was not a topic they assessed until this year.

“This was the first time we looked at suicides in farmers in Canada and regrettably we did see high levels of suicide ideation or thoughts of suicide,” said Jones-Bitton.

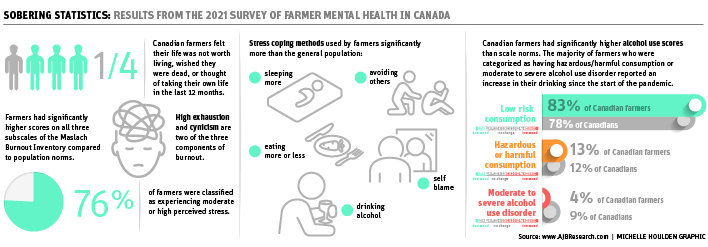

The survey is used to determine levels of stress, anxiety, depression, burnout and coping methods of farmers in Canada and compare them to the general population.

It showed three-quarters of participating farmers experience moderate to high-stress and half experience anxiety or depression.

“Most of that being mild depression, but still considerable moderate and severe depression. We also saw that resilience levels were lower than the reference populations,” said Jones-Bitton.

The survey also determines resilience scores, and 83 percent of farmers had lower scores than the general population of the United States.

Farming is an isolating career, so mental health issues can be fostered by feelings of loneliness or lack of human connection.

“As a human species, we’ve been designed and have evolved to be part of groups. So, for even the most introverted people among us, it’s important we feel connected to others,” said Jones-Bitton.

Farming is a profession with many stressors out of the farmer’s control. Weather, market prices and equipment breakdowns can take a toll on mental health.

Weather and market prices have been factors in recent years. With drought and floods covering a large part of the Prairies and supply chain issues from overseas causing market fluctuations, farmers have been dealt some serious blows in the last five years.

Since the first study, Jones-Bitton said there was nearly no change in the state of farmer mental health.

“The mental health outcomes we looked at were fairly on par with what we saw five years ago. Where we had new programs developed, we might have hoped to have seen the situation improve. But who knows if COVID just kind of took away any gains we saw there,” said Jones-Bitton.

With the survey being conducted in the heart of the pandemic, additional stressors such as labour disruptions, illnesses, concerns about getting sick and further social isolation may have been factors in the numbers staying high.

Jones-Bitton said one coping strategy farmers excel at is maintaining sense of community, usually living in rural communities where things might be more “close-knit.”

But a strong sense of community is not an end-all, be-all cure for mental health problems.

Programs and supports have become more accessible to farmers in recent years as it became more common to have conversations surrounding mental health issues. Manitoba has its own Farmer Wellness Program and Ontario has the Farmer Wellness Initiative.

These programs provide counselling with people who understand the farming lifestyle and the struggles that come with it.

“It’s been getting better. In the last five or six years we’ve been studying this area we’ve seen a lot of important strides. People are talking about mental health and farming more. Traditionally, that wasn’t the case,” said Jones-Bitton.

Other provinces are starting to set up programs, but a family doctor and the Canadian Mental Health Association are available if farmer specific programs aren’t accessible.

“Traditionally, farmer mental health has been understudied,” said Jones-Bitton. “We’ve been doing a lot of work over the last few years and groups have been raising awareness and attention to the issues. I do think it’s getting better.”