Three years after being shut out of their prime markets, Saskatchewan elk producers say it’s nice to be included in recent government compensation programs.

Still, Luke Perkins, president of the Saskatchewan Elk Breeders Association, said the fact that bulls were not included highlights a lack of understanding about how the industry works.

“Our bulls are like our cow-calf operation,” he said from his farm at Star City.

“We have put in that request.”

Under the federal-provincial bovine spongiform encephalopathy recovery program that ended last month, Saskatchewan producers applied for compensation for 472 slaughtered elk.

Read Also

Trade war may create Canadian economic opportunities

Canada’s current tariff woes could open chances for long-term economic growth and a stronger Canadian economy, consultant says — It’s happened before.

That compares to 42,373 steers and heifers, and 5,401 beef cows and bulls.

“It was a huge problem trying to get animals in” to slaughter plants, Perkins said.

“Elk came in at the back of the pack.”

Dave Boehm, director of financial programs at Saskatchewan Agriculture, said access to slaughter plants was a limiting factor because abattoirs that often process elk were busy doing beef.

“We can’t tell the little packer in small town Saskatchewan what he should and shouldn’t kill,” he said.

Elk remain eligible for assistance under the Saskatchewan program announced Sept. 12.

Boehm said it could take another week before the regulations for that program are passed. The department is registering animals, but is unable to make payments until the regulations are in place.

He said 230 elk were registered in the first week of the program, compared to 4,850 steers and heifers.

Perkins agreed the industry is smaller than the beef sector, but said each link in the agricultural chain is important.

He said politicians didn’t listen when South Korea closed its border to Canadian elk velvet, but they’re listening now.

“Hopefully we’ll be recognized on a level playing field,” Perkins said. “We are an extremely viable industry with a lot of untapped potential.”

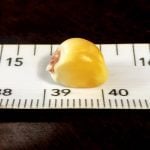

Velvet is selling for $18 a pound; the world price is $55.

“China is our only buyer right now and they have no competition so they can name their price,” Perkins said.

The province produces about 100,000 lb. of antler velvet a year. At the low price it’s worth $1.8 million. At the world price it would bring in three times that much.

Aside from being shut out of their main velvet market, elk producers are also prevented from selling meat to the United States under the BSE ban. They also suffered through two years of drought.

Perkins said this has backed some producers into a corner. Rumours that at least one producer had shot and buried his herd could not be confirmed.

“There are producers who have more animals than what their pastures can handle,” Perkins said.

“They’re running out of feed. They’ve borrowed to capacity. Desperate people do desperate things.”