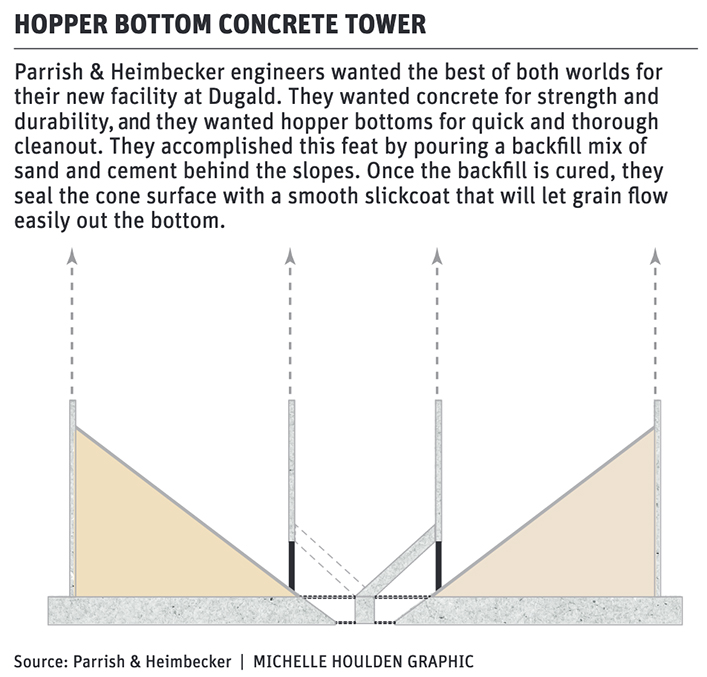

DUGALD, Man. — Parrish and Heimbecker engineers wanted the best of both worlds for their new grain terminal at Dugald, Man.: concrete for strength and longevity; hopper bottoms for quick and thorough cleanout.

They built bins with both.

They used a technique called slip form construction, a style common in grain elevators. A backfill mixture of sand and cement is poured behind the cone slope forms at the bottom of each tower. After the mix cures, they seal the cones’ inner surfaces with a slick coat of abrasion-resistant concrete.

Once pouring starts, the operation runs non-stop for six days until finished. There are no seams, and in the world of concrete, no seams means greater strength and longevity.

P&H construction engineer Zach Harrison explained the process while guiding a media tour in November.

“First, we pour our tunnels underground, then we pour the mat slab, which is the foundation for each silo. We set the circular forms on the slab.

“The walls are seven to eight inches thick. The rebar goes in the vacant space, just like in a basement wall. Then they drop the concrete in, and the gap fills up,” said Harrison.

“We have a hatch halfway up so guys can go in there to form up the cone. They have to form it so the slope is correct for the grain to flow out the bottom.

“Once the forms are secured, that’s when the conveyor dumps in the sand and cement mixture. After the forms come down, they give the cone surface a slip coat smooth concrete that allows grain to flow out the bottom.”

He said the new facility is capable of handling 150-car trains, with no need to break up the train for filling. The continuous loop allows the train to continue forward movement throughout the filling process, so it can be back on the CN main line in 10 hours.

P&H operates its own locomotive to shuttle the train once the cars arrive.

The high efficiency concept doesn’t apply only to grain leaving by rail. It also applies to grain entering the plant by truck.

Gone are the days when a guy runs out with a bucket. Now, there’s an automatic probe mounted on a hydraulic arm that pushes the probe into the grain.

Someone in the office presses a button and the probe removes a two-pound sample and deposits it in a bucket, ready for grading.

“We take a sample from every truck before it enters the dump pit area. In the lab, tests are run immediately. The probe is located way back at the entrance to the driveway so the lab has more time before he’s up to the dump pit,” says Harrison.

“We would typically have a couple trucks lined up, so there’s a time buffer between the probe and the dump. If we have to reject a load, there’s plenty of time to catch it.

“The first glance assumption is that this process must really bog down the system. Not so. Only five minutes pass from the time the probe fetches a sample until the time the driver gets the OK to dump. Ten minutes later, he drives away with his cheque and the grain is headed toward the appropriate bin.”

Harrison says this system is fast. Theoretically, the plant can do six or seven trucks an hour but that depends on how much time passes when the driver comes in, signs his name, and maybe stands around to talk for a bit. That’s all part of the business, says Harrison.

“We have the ability to load railcars directly from trucks, but we prefer not to. We receive grain from trucks at only 500 metric tonne an hour whereas we load rail cars at 1,500 metric tonne an hour.

“When we bring grain into the elevator we can clean it, sample it, and then store it. After that we can ship it via truck or rail at a high capacity, and take samples as we do so.

“We clean wheat at about 240 tonnes an hour. We clean canola to one percent dockage at 100 tonne an hour. We have automatic samplers on the bucket elevators and on the cleaning systems. It all comes into the office through the vacuum tube.”

The level of cleaning depends on the contract. The Thunder Bay terminal has cleaning facilities, so there are times dirty grain is shipped east. And there are times when a contract specifies no cleaning.

The plant has a sophisticated inventory system called Human Machine Interface (HMI). All the sensors are programmed into it, giving managers a precise look at how many tonnes are in each of the 10 silos. There are 22 bins including the interstice bins.

Harrison says the need for cleaning was not as great in previous generations of elevators. In recent years, P&H has erected a half dozen new elevators. Each time it designed a cleaning system sized for the conditions.

Those designs were often used on future projects so each new facility has a bigger and faster cleaning system than the previous one. The Dugald plant will ship one 150-car unit train approximately every other week.

Harrison says it needs to receive grain, clean grain and load enough grain bi-weekly to fill those cars, without incurring overtime shifts.

“That’s why we’ve incorporated a super flow cleaning system. The product goes over a rotary machine and then the byproducts go to an indent machine to separate wheat heads from clean wheat.

“At the Dugald elevator, we’ve added in a reclaim rotary. Anything bigger than wheat goes over the top. Anything smaller than wheat goes through.

“On our second separation, anything smaller than wheat falls through and that wheat size is your clean in the middle. The top stuff goes over the top screen and goes to the indent machine, which separates out and picks wheat out of that larger stuff.

“We clean at a very fast pace because we know we have a reclaim system. The fines that fall through the bottom screen would normally go to cracks and fines and blend it in to clean product. We send that material to a reclaim rotary that separates out small wheat.”

Canola is cleaned down to one percent dockage for a good reason. Dockage takes up space in the railcar.