New report says operations with sales of more than $2 million can appear to the public as industrial or corporate entities

Farmers could lose public support and local influence if they become too few and too big, warns an agricultural economics analysis firm.

Full-time farmers are becoming scarce and atypical of the societies they live in, even in rural communities.

“The economic dominance of the very large farms serves to weaken the link, accepted implicitly in the past, between farms, rural households and families, and ownership/management of land,” writes Al Mussell, lead economist at Agri-Food Economic Systems, in a November policy paper.

“Farms with (farm cash receipts) ranging well over $2 million, even though almost all are likely to be family owned, can carry the appearance or connotation of an industrial or corporate entity.

“As this occurs, some may reasonably begin to expect that farms should be regulated much more like corporate or industrial entities and question the preference and exemptions for farms to certain regulations ranging from labour to transportation to tax treatment, etc. that embody the received view of farms as extensions of the household.”

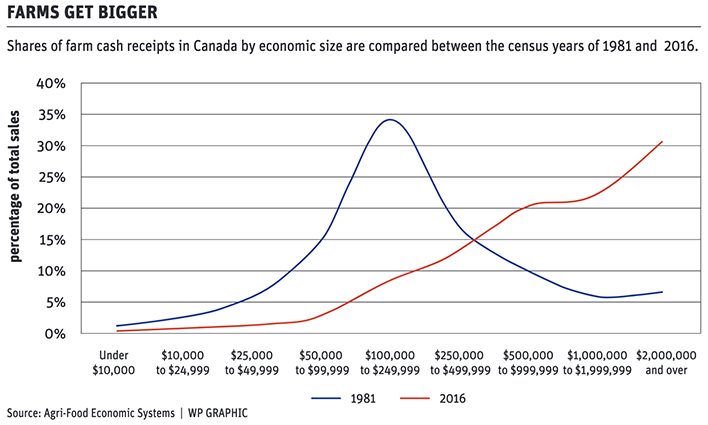

Mussell argues that farms have become bigger with time and the spread between small, medium and large farms has also grown, with the biggest becoming much more dominant than in the middle-dominated past.

For decades, farm sizes had a statistical bulge in which small and large farms formed two small ends of a distribution. Most farms could be described as medium-sized, but that size grew over the years.

Distribution began to shift in 1991, with proportionately more farming done by the largest farms, even though most farm cash receipts were still received by medium-sized farms.

That pattern changed substantially by 2001, when the largest farms became the highest-earning sector of agriculture and the smallest fell further behind.

By 2016, it was clear that most farm cash receipts were earned by farms that grossed more than $500,000 per year, and much of that was earned by $1 million-plus producers.

The introduction of disruptive, revolutionary technology is unlikely to level the playing field, said Mussell, and seems more likely to skew success even further toward big farms that can afford the technology.

He thinks this is worrisome in terms of preserving farmers’ local and political influence. Whether it’s over local zoning and nuisance issues or national environmental regulations and safety net funding, a farm sector that contains only tiny, low-capital farms or huge multimillion-dollar operations might find few friends.

Mussell suggests governments should help create conditions for small and medium-sized farms to keep growing, as they once did, rather than simply leave the industry and see the biggest farms expand.

That would be a tricky task because it would be counter-productive to hamstring the biggest, most successful farms. However, options must be considered that allow small and medium-sized farms to stay in the industry and continue to play a role. There won’t be much of a farm community left if medium-sized farms disappear, and small farms operated by part-time farmers have little in common with the big farms.

“As the distribution of farms pulls apart from the economic significance of farms, it is likely to erode the cohesive basis for achieving consensus and effective action among farmers,” said Mussell.

An ethic of “rugged individualism” appears to have taken over in farming circles, but that won’t well address areas where farmers probably need collective action to achieve good results, including herbicide resistance, wildlife habitat preservation, sustainability practices and animal welfare standards.

By finding a way to keep medium-sized farmers in agriculture while not discriminating against the large ones, farmers, farm groups and policymakers could do much to preserve the farming community.