Canadian pulse crop analysts and brokers are interpreting poor monsoon

rains in India as a bullish sign for domestic markets.

But a broker familiar with the Indian subcontinent says people here are

a little too excited about what is happening over there.

“I think it’s a bit overblown,” said Ashok Fogla, president of A.F.

International Corp., an American brokerage firm that specializes in

pulse trade with Asia.

Statistics released by the government of India show that between June 1

Read Also

Trade war may create Canadian economic opportunities

Canada’s current tariff woes could open chances for long-term economic growth and a stronger Canadian economy, consultant says — It’s happened before.

and July 31, the country has received only 70 percent of its normal

rainfall. India’s meteorological department rates 26 of 36 subdivisions

as having deficient or scanty rainfall.

Fogla points out that the monsoon season runs from the beginning of

June to late August or early September. While the rains have been poor

during the early part of the monsoon season, what happens at the end is

far more crucial.

“My contention is that I think it’s too early. It’s like saying in

November you don’t have any snow cover on the ground so your crop is

going to be in trouble.”

India has two growing seasons – one in the summer and one in the

winter. The summer crop is seeded shortly after the monsoon season

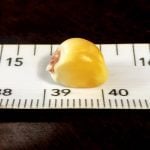

starts. Only two pulses, mung beans and black matpe, are grown in the

summer. Farmers usually harvest three to four million tonnes of those

crops.

It’s during the winter months that 70 percent of India’s pulse crop is

grown. The crop is planted in October and eight or nine million tonnes

of pulses are harvested in March or April. This is the crop that

Canadian farmers want to watch.

Fogla said the summer crop is undeniably drought stressed, but if the

rains come at the end of the monsoon season the winter crop could be

fine.

“If it rains well in August and early September, the farmer is going to

plant the hell out of the winter crop.”

The government of India also has plenty of stocks of rice and wheat on

hand to feed the nation in the event of a crop failure, he said.

While the situation in India is far from resolved, it is clearer in

Australia, which is Canada’s main pulse competitor. Fogla said pulse

production will undoubtedly be down in that country due to drought.

Pulses are grown in five provinces in Australia. In Western Australia,

where production is usually around 40,000 to 50,000 tonnes, the drought

has had a devastating effect.

“That crop is more or less toasted,” said Fogla.

In South Australia, the crop is in good shape. That region usually

produces 300,000-500,000 tonnes of pulses, including 250,000 tonnes of

field peas.

In Victoria, where field peas, lentils and broad beans are grown, and

Queensland, where production is predominantly chickpeas, it’s a mixed

bag, said Fogla. But in New South Wales, a big chickpea production

area, there is absolutely no rain.

“The crop either didn’t get planted or got decimated.”

Fogla said a good Australian chickpea crop would yield 400,000 tonnes.

This one looks like it will be in the range of 75,000-170,000 tonnes.

What happens to the rest of Australia’s pulses will depend on how much

rain falls in the next six to eight weeks.