Greg Thorstad can imagine a day when farmers will be able to order and receive parts for broken machinery in a matter of hours.

His vision looks something like this: A farmer walks into a shop, looking for a hard to find item, for example an old model gasket or gear. Staff receive the order, load its 3D design in a computer and hit print, sending a command to the shop’s in-house 3D printer, which builds the object, micrometre by micrometre, out of melted plastic. A few hours later, the farmer picks up the part and goes back to work.

Read Also

Canadian Food Inspection Agency red tape changes a first step: agriculture

Farm groups say they’re happy to see action on Canada’s federal regulatory red tape, but there’s still a lot of streamlining left to be done

Look hard enough and you might even find someone willing to make it for you today.

Thorstad has already done small custom jobs, creating designs and repairing things like toys and can openers using a desktop 3D printer in his computer shop in Outlook, Sask.

And he’s not alone. New businesses are being built around 3D printers small and large.

Similar processes are occurring within the walls of engineering firms, start-up companies, design labs and the homes of hobbyists around the world — driving what New Scientist magazine has dubbed the second industrial revolution.

The process works like an inkjet printer, taking a digital image and creating a tangible object out of finely layered plastic, metal or other material. Objects are built rather than subtracted from other materials, which reduces waste.

The technology has been around for more than a generation, but advances and dropping prices have made printers available to a wider array of manufacturers and brought do-it-yourself printers into homes. This proliferation has fostered a “maker movement” and fuelled new interest in a technology that is already used by the makers of everything from cars to prosthetics.

Experts say the potential is far reaching. A 3D printer in a North American home might save its owner a trip to the department store when he needs a bath plug or a latch for a gate. Such a machine could also put much needed tools in the hands of small-scale farmers in the Third World.

American entrepreneurs plan to take the same premise and produce 3D printed meat out of live cells.

And while today’s combines weren’t printed, manufacturers have been using the technology for years, including many of the agricultural machinery brands familiar to western Canadian farmers.

“There is some work around actually 3D printing food, but that stuff is all kind of theoretical at this point. I don’t think we’re at a stage where we’re going to be replacing crops with 3D printed food at this time,” said Doug Angus-Lee of Javelin Technologies, a Canadian company that provides mechanical design software and training.

“However, all the people who make equipment for agriculture, whether it be food handling equipment, tractors … those companies are all using 3D printing to prototype and design their parts.”

Analysts expect the value of the 3D printed market, pegged at $777 million in 2012 in one report, to grow by billions over the next decade, with manufacturing and 3D printed prototype parts in the aerospace and automotive sectors accounting for much of the growth.

Designers in the agricultural manufacturing sector can use printers to test pieces, see how they look, make modifications and quickly make new designs.

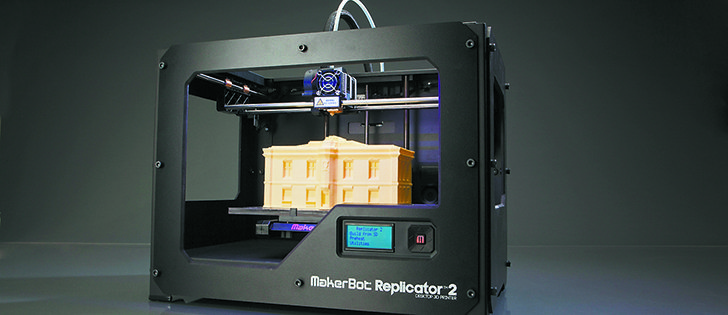

“That all might be the same day,” said Thorstad, who distributes the desktop-sized MakerBot replicator, which is used by professional designers, enthusiasts and artists.

MakerBot says it has sold more than 22,000 3D printers worldwide since 2009. The company was recently purchased by Stratasys, a manufacturer of higher-quality, industrial-sized printers that can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, in a deal valued at $403 million US.

Stratasys merged with another manufacturer, Objet, last year, and reported revenue of $98 million in the first quarter of 2013.

While it’s not the cheapest desktop 3D printer available, the MakerBot has developed a loyal following and claims a large portion of the market share for both personal and industrial use.

For less than $3,000, anyone can own a desktop printer capable of making three-dimensional objects out of simple strips of ABS and PLA plastic, so long as the object is smaller than 11 by six by six inches and the owner can make the designs or has access to existing ones.

The printed material resembles that of Lego material, said Thorstad. One kilogram of plastic costs $56. A project the size of a fist might use $5 worth of material, he said.

“But the issue is, you still have to draw the part (in a computer-aided design program),” said Thorstad. “We’re at a tipping point where you’ll be able to scan the old part and get it, but we’re a ways away from it.”

Agco employees in the United States have had a 3D printer at their disposal for a few years.

Monte Rans, a senior technical project engineer with the company, said the technology can help bring products to market faster. He used a larger industrial printer to design plastic models of the company’s 9000 Series planters.

“I had a bearing in it and everything and actually used it in my (research and development) lab to do some verification that what I did was an improvement over the current meter,” said Rans.

“It worked very well.”

Agco’s machine can make parts that fit within a 14-inch square, he said, although bigger machines are available. To get around size limitations, engineers will often break up a design into smaller parts and then assemble them into a larger piece after printing.

At five feet long, four feet deep and four feet tall, the machine, which cost $150,000, is strictly for industrial use, said Rans. Individual jobs can take anywhere from a matter of hours to a few days to complete and use a few thousand dollars worth of materials.

Those costs can add up, but they’re advantageous for projects that might take considerable time and tens of thousands of dollars to manufacture just once out of aluminum die casting.

“It gives you the opportunity to have a part in hand without the major cost of tooling and the lead times required for that, “ said Rans.

He said 3D printing can cut down on the development time for equipment, but it won’t necessarily cut down on testing time, which still requires the real thing. Durability is one of the shortcomings when the plastic test parts go out to the field.

“Last summer they’d leave for the night and when they come back the next day the thing has a permanent warp to it. It’s actually deformed because of the heat and a little bit of load on it,” he said.

Material innovation is another burgeoning industry as companies look to supply manufacturers with the toughest, most durable material. In early July, another printer maker, 3D Systems, unveiled a new material for its machines that it claims mimics the performance of injection moulded plastic.

“There’s lots of experimentation going on with different materials,” Thorstad said.

“They’re working with nylon right now, so it’ll be even different yet.”

Thorstad first picked up a MakerBot as a customer three years ago. With no design background, he’s had to learn how to draw the three-dimensional designs on a computer, which can be an impediment for laypeople, along with cost.

Yet as a distributor of the desktop printer, he’s dealt with everyone from engineering firms and entrepreneurs opening up their own design shops to inquiries from schools and hobbyists.

He thinks printers will become more commonplace as prices for the desktop models come down, possibly becoming a fixture in homes.

Doubtful? Microsoft has announced that its Windows 8 operating system will feature built-in support for the technology.

“I’m just amazed how many go out,” said Thorstad. “And we can’t keep up.”