CORNER GAS had a great episode in which the grandmother of Dog River’s mayor suggests they build a giant hoe to put the town on the map. Unfortunately, the “e” in hoe isn’t audible and much innuendo ensues.

“They do attract people,” Lacey notes pragmatically about the ho(e) “and they certainly generate revenue.”

Hearing Montmartre’s plans to build an Eiffel tower, I’ve become curious about this rural phenomenon. By my count more than 479 rural communities west of Ontario have erected giant versions of small things or smaller versions of giant things as town landmarks.

Read Also

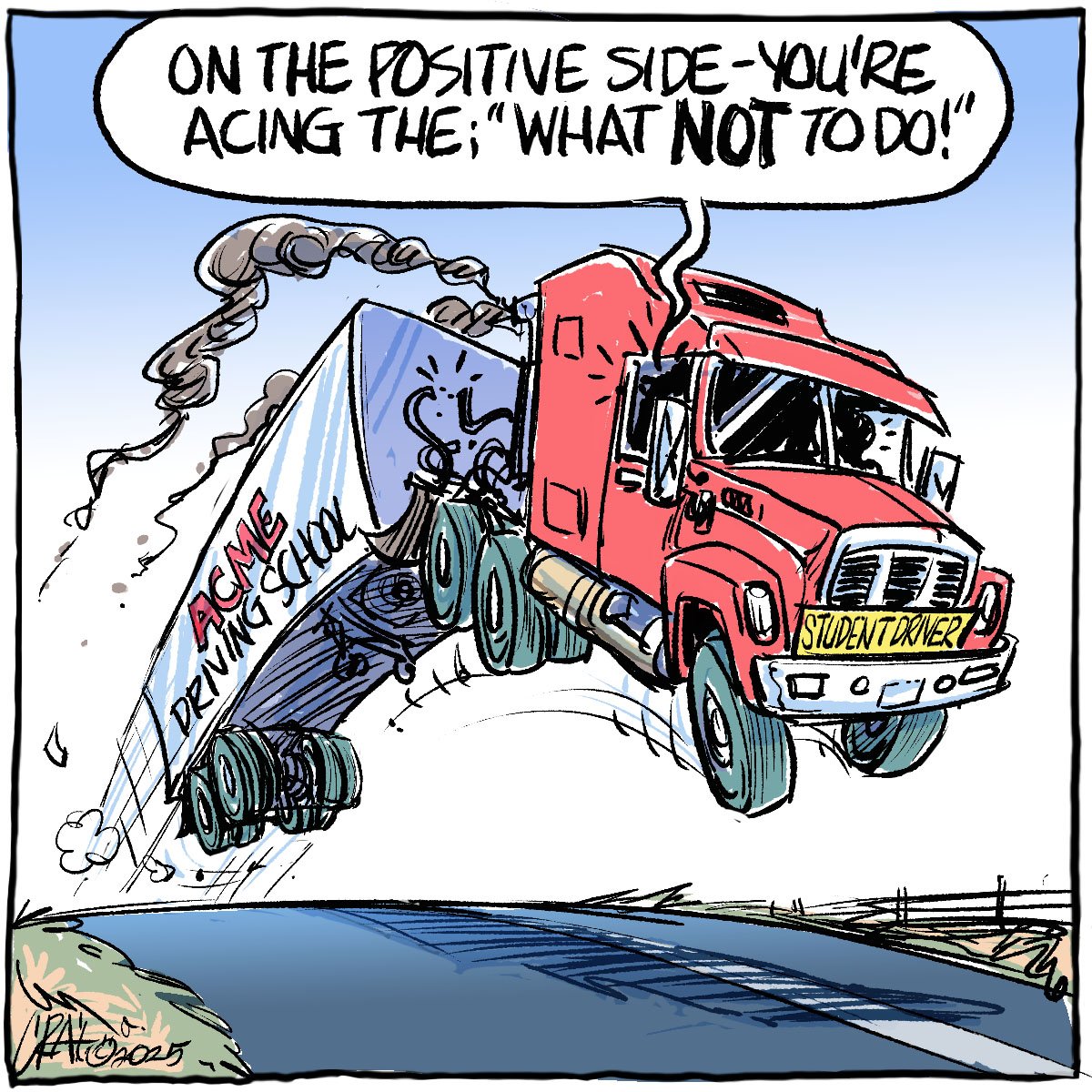

Efforts to improve trucking safety must be applauded

The tragedy of the Humboldt Broncos bus crash prompted calls for renewed efforts to improve safety in the trucking industry, including national mandatory standards.

It’s quite a collection. Everything big, from a mighty mosquito, sultry woman, piggy bank, coal oil lamp, cowboy in a bathtub, fighting bears and shore birds, to an opera house, Viking ship and Eiffel tower.

The tallest are Drumheller’s T-Rex (82 feet) and the Altona “Painting on an Easel” (80 feet). The St. Paul UFO landing pad probably holds the weight record at 130 tonnes.

My favourites are Kelvington’s giant hockey cards (so Canadian) and Vulcan’s Starship Enterprise (my personal fantasy.)

What is it that seems to push rural communities to build these quirky icons? Perhaps in part it’s the loss of their town sentinels – the grain elevators or the beehive burners of logging towns – that once anchored their place on the rural horizon.

But it may also reflect the fact that rural Canadians sometimes feel invisible.

Canada’s major social, economic and political decisions are mostly made by folks who live in cities. The agenda for what matters and who counts is set by urban concerns. Decision makers tend to fix their gaze on other cities; rural Canada becomes the “empty space” that must be crossed in order to get there.

Perhaps then the “big things” are a small way in which rural Canada expresses its hopes and protests: “Hey! we’re here; we matter; we have a future; take us into account.”

As a seminary professor, I am rostered at a place in Manitoba called Thallberg. It doesn’t show up on Mapquest. Only the locals know the name.

But a hardy group of souls gather each week at another rural icon, their steepled church, to remember its history, tend its spirit and reforge community.

They believe something quite contrary to Canadians’ general worldview. They believe God loves (is!) community. They know that most of the biblical promises were given to communities rather than individuals.

So to casually dispose of a village in the name of economic growth or consolidation or efficiency is not progress for them. It’s communicide.

I see rural big things as a proud claim to and plea for the life of rural communities.

But of course securing that life means doing more than building a 50 foot fibreglass farmer to lure passersby off the highway hoping they’ll drop a few bucks at the local store.

It takes the hard work of building new alliances between farmers and merchants, churches and town councils, teens and seniors. It means growing a resilient web of relationships that can generate effective local economic and social planning. And that’s a “tall” order.

Cam Harder is associate professor of systematic theology at the Lutheran Theological Seminary in Saskatoon.