By Paul Orsak

Orsak is chair of Grain Vision, a grain industry coalition. He farms near Binscarth, Man.

The barley industry in Canada is at a crossroad. Demand for malted barley and malt products is growing around the world, largely driven by increased disposable income in developing economies.

The malting industry is ready to expand. The world needs a half a million tonnes of new malting capacity every year for the foreseeable future. But where will these new plants be built? According to recent comments from malting industry executives, the answer appears to be “anyplace but Canada” as long as we refuse to reform our marketing system.

Read Also

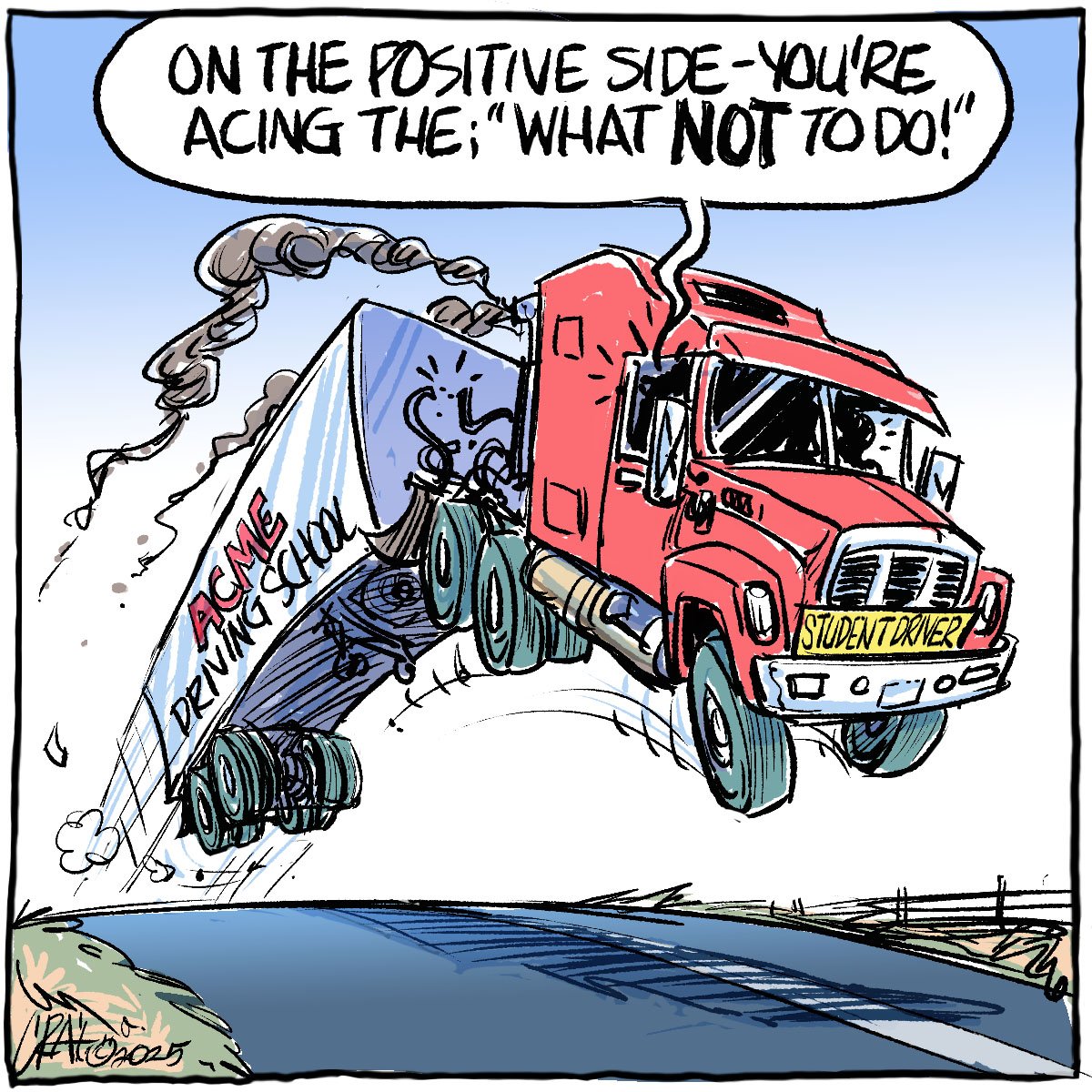

Efforts to improve trucking safety must be applauded

The tragedy of the Humboldt Broncos bus crash prompted calls for renewed efforts to improve safety in the trucking industry, including national mandatory standards.

These comments are not threats. They’re based on commercial realities and choices investors have. We still have an opportunity to have this growth centred here. Canada is uniquely positioned to capitalize on this expanding marketplace. But that won’t happen if Canada does not immediately solve its internal squabbling over the Canadian Wheat Board.

What happens if we don’t get this right? Our malting industry will wither. Jobs and investments will go to other countries. Barley production in Canada will shrink.

That would be a shame, since Western Canada has a natural competitive advantage in barley production. It would be a travesty to squander that advantage because of entrenched opposition to change.

We therefore have a choice to make. We can continue to argue about the CWB or we can lay the foundation for a new and reinvigorated barley value chain in a vibrant and competitive industry.

Canada has a real chance of becoming the acknowledged powerhouse in malting barley internationally. However, the unrelenting political and ideological opposition to marketing reform has, and is, costing us invaluable time.

This debate is not about the CWB. It’s about something exponentially more important: the future of the Canadian barley and malting industry.

It’s time for the CWB and its board of directors to realize that it isn’t about them or the single desk. It isn’t about their personal desires and authority nor is it about their individual political allegiances.

Can Western Canada rise to the challenge of creating an internationally competitive industry? This is a question about real and substantial economic growth. It’s about building something large and significant.

Never before has there been so much promise in the barley business; especially for farmers. To capitalize on this promise, we must forge an environment where industry can invest in new capital, innovative technology, infrastructure and processing. Farmers will see enormous benefit from being active participants in this revived value chain, a chain that is built for the new world economy.

The government of Canada has indicated it will introduce legislation to end the CWB’s marketing monopoly on barley. It’s time for this change. This legislation is a prerequisite to farmers’ realizing the growing potential of barley production.

Those who are choosing to ignore this reality are putting politics and ideology ahead of what is good for farmers.

It is time to create and embrace a new environment, one that will allow emerging opportunities to be fully realized. This means we must put aside old arguments and focus our collective energy on a new, positive future that is within our grasp.

By Ken Ritter

Ritter is chair of the Canadian Wheat Board’s board of directors. He farms near Kindersley, Sask.

Federal agriculture minister Gerry Ritz recently told the media that he intends to “crack the nut that is the CWB.”

It is the opinion of the CWB’s board of directors that the minister cannot bring forward legislative changes to barley marketing without cracking a whole lot more.

At risk is a process put in place to give grain producers the final say in how their grain is marketed – and the trust that we should all have in the democratic process.

Ten of the 15 directors of the CWB are elected by western Canadian wheat and barley farmers. This is democracy. It makes the CWB accountable to producers and ensures that it works to protect and promote farmers’ financial interests.

While accountable to farmers, the CWB is also governed by the Canadian Wheat Board Act, which underwent significant amendments in 1998.

These amendments, made after extensive consultations with all affected parties, established the CWB’s board structure and put the future of the agency squarely in the hands of farmers.

The reason Parliament agreed to this move was quite simple: the CWB’s single desk powers are controversial. What better way to deal with the division and the controversy than to give the people directly affected, namely the grain producers of Western Canada, the final say?

Consulting the board of directors does not mean that the government dictates what it wants to do. To simply dictate is to fail to recognize that the board of directors is a legitimate representation and expression of farmers’ views. It fails to recognize that 10 of the 15 directors have received a mandate from producers to reflect their views around the board table.

Consultation does mean seeking advice and the advice of the CWB’s board of directors on this issue has been clear and unwavering: without the power to act as a single desk seller, there is very little value that the CWB can add for the barley producers of Western Canada.

To open up the market as of Aug. 1, 2008, without any consideration given to issues like access to facilities, capital, assurance of supply and many others, would only result in the CWB becoming at best a bit player in the barley market with no capacity to add real value for farmers.

This is not a matter of ideology or clinging to the status quo at all costs, as some would suggest. It is a matter of business and it is a matter of listening to the farmers who have elected us, to their insights and concerns about their businesses, and of representing those views to the government.

The CWB was hoping to have meaningful consultation with minister Ritz in Ottawa on Feb. 12 but it did not happen.

There was no breach of confidentiality coming out of that meeting. The CWB simply stated that talks would not continue because of lack of common ground. Farmers were owed an update and the CWB provided it.

Unfortunately, this unleashed a barrage of public criticism from the government, aimed at the CWB, its directors and its supporters.

Such criticism only serves to foster uncertainty. Uncertainty disrupts markets and ultimately impacts the pocketbooks of farmers and other industry players. And frankly, the farmers I hear from are getting tired of the politics and mudslinging, no matter which side they support.