SEVERAL weeks ago, I attended a prairie funeral in Toronto. An overflow crowd of more than 1,000 people, including governor general Adrienne Clarkson, jammed the aisles of St. James Cathedral to hear scripture read by former prime minister Joe Clark and retired senator Lois Wilson.

We heard a letter of condolence and praise written by freedom fighter Nelson Mandela. We listened to a sermon in which former South African archbishop Desmond Tutu declared himself to be “a slightly less bad person for having known [the deceased]”.

Who were we mourning and whose life were we celebrating? Born in Edmonton in 1919, raised in Caron, Sask., Edward Walter Scott worked in Prince Rupert, Winnipeg, Toronto and Kelowna before being elected primate of the Anglican Church of Canada in 1971.

Read Also

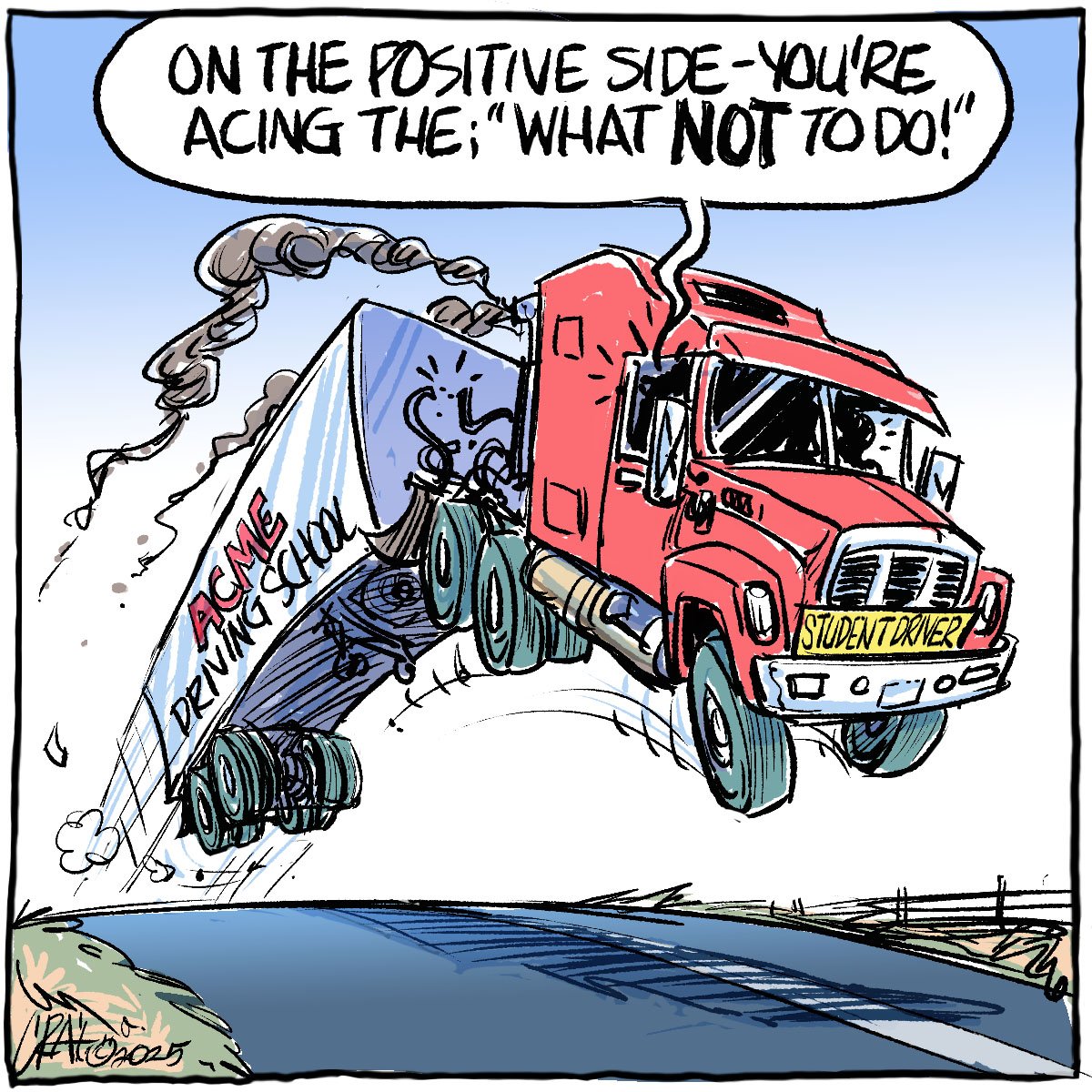

Efforts to improve trucking safety must be applauded

The tragedy of the Humboldt Broncos bus crash prompted calls for renewed efforts to improve safety in the trucking industry, including national mandatory standards.

Archbishop Scott (everyone called him Ted) led the Anglican church for 15 turbulent years. He consistently pushed the church to focus its attention on the places where morality and economics intersect.

In Prince Rupert and Winnipeg, Ted had significant first-hand exposure to the racist policies of the Canadian government and Canadian churches in dealing with First Nations people. He supported the dismantling of the residential school system.

In the 1970s, when the government created the Berger inquiry into the effects of a proposed oil pipeline in the Mackenzie Valley, Scott helped lead the Anglican church into a relationship of solidarity with the Dene of the Northwest Territories.

When he was criticized by business leaders for being too confrontational, he replied “I couldn’t be a disciple of Christ, and take it seriously, without realizing there are times for confrontation on moral and ethical issues.”

Apartheid was an example of institutionalized racism that Canadians were more united in fighting because it was so far away. In the early ’70s, Canadian church leaders began meeting with bank executives to discuss their international loan policies. In the face of resistance, leaders like Ted Scott began attending annual general meetings of the banks and proposing resolutions on behalf of church shareholders to change lending practices.

Church members began placing stickers on their cheques that read “No Loans to Apartheid.” The stickers gummed up the automated cheque processing machines, forcing them to be processed by hand.

By 1978, the first Canadian bank announced it would make no new loans to South Africa and the other banks followed suit. Ted called his effort to end apartheid “the greatest challenge of my life.”

In 1986 prime minister Brian Mulroney appointed Ted as Canada’s representative on the Commonwealth Eminent Persons Group to pressure South Africa to end apartheid. That same year he visited Nelson Mandela in prison. In 1994, Ted attended Mandela’s installation as president of the Republic of South Africa.

While he was primate, Ted Scott, the prairie preacher’s kid, was formally adopted by the Nisga’a in gratitude for his support of their aboriginal rights. There was a great debate about which of the four clans – eagle, wolf, killer whale or raven – he should be adopted into.

Finally, the women decided that since he was the spiritual leader of all the people, he should be adopted into all the clans. His Nisga’a name was Gott Lisims. It means heart of the nation.

Christopher Lind writes frequently in the area of ethics and economics. He is director of the Toronto School of Theology. The opinions expressed in this column are not necessarily those of The Western Producer.