Sandecki writes from Terrace, B.C. This column previously ran in the Terrace Standard.

Owning land has always been a thrill and an accomplishment for most people.

From the earliest settlers of the American West who – if Western movies can be believed – raced to file for a homestead in covered wagons or on horseback, to the European immigrants who came to Canada in the early 1900s in search of 160 acres of untouched prairie, land has fired the imagination.

Physical dimensions of the plot make no difference in that feeling of ownership.

Read Also

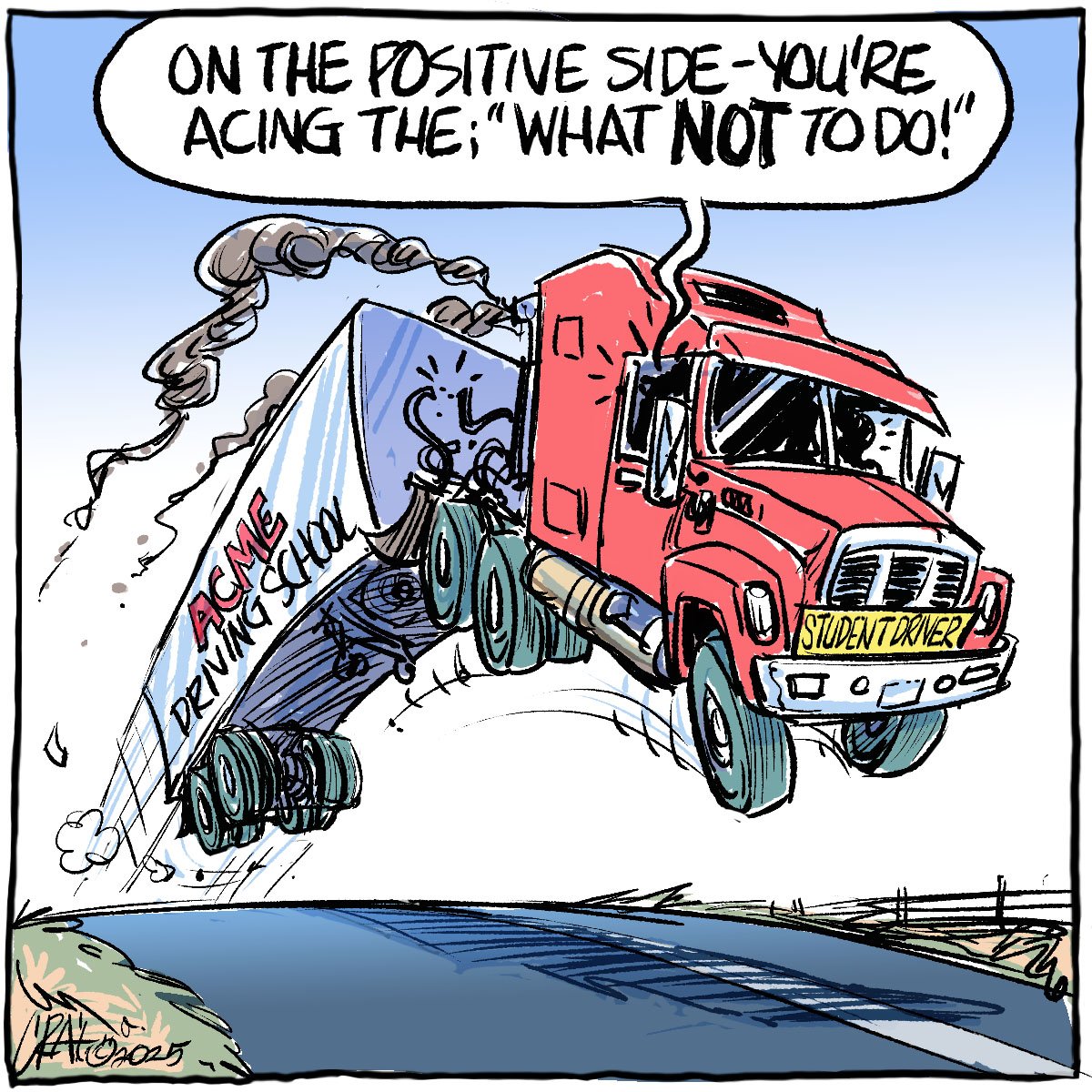

Efforts to improve trucking safety must be applauded

The tragedy of the Humboldt Broncos bus crash prompted calls for renewed efforts to improve safety in the trucking industry, including national mandatory standards.

Last year, a County Cork Irishman established a company called Auld Sod Export Co. and began shipping 12-ounce yellow packets of sanitized Irish soil to American citizens homesick for the Emerald Isle. Within a few months 160,000 packets at $15 US each had been sold to transplanted Irishmen who wanted a dribble of Ireland to sprinkle on a casket, as potting soil to grow genuine Irish shamrock, or just for good luck. One customer paid $100,000 to have his entire casket covered in the old sod.

But an even smaller piece of real estate caused a stampede in 1955 when the Quaker Oats company searched for an advertising gimmick to sell its ready-to-eat breakfast cereals. It needed an inexpensive way to counter competitors who enclosed cheap prizes in their boxes of cereal – spinning tops powered by elastic bands, plastic submarines propelled by baking soda, whistles, buttons, soldiers and airplanes.

Quaker Oats sponsored the radio program Sgt. Preston of the Yukon featuring a red-coated Mountie and his team of Huskies led by King, which gave pint-sized listeners romantic notions of the gold-rich Klondike.

Bruce Baker, the Chicago ad man stuck with the task of digging up a super sales pitch, hit upon the idea of giving away with every box of Quaker Oats Puffed Rice and Puffed Wheat ownership rights to one square inch of Yukon territory.

Baker’s plan called for each box of cereal to be stuffed with a land deed. A legal deed would be designed, embellished by gold filigree around the edges, an embossed stamp and space for the recipient to sign his name. Each seven by five inch deed would be 35 times larger than the piece of land it represented.

Quaker Oats reluctantly agreed to the scheme. Baker flew to the Yukon and with local help, travelled upstream in a small boat to select and inspect a 19.11 acre plot about five kilometres upstream from Dawson. He paid $1,000 for the land, and due to frostbite after his boat was sluiced with frigid water, he later had to have one leg amputated below the knee.

Legal advice deemed it unnecessary to register the individual deeds, given out by the Klondike Big Inch Land Co., an Illinois subsidiary established to handle the cereal company’s land affairs, so only Quaker Oats owned land. To avoid problems over royalty rights, the deed stipulated no mining on the property was allowed.

The land was mapped into one inch squares, and each square given an identifying number. In all, 21 million numbered deeds were printed up and on Jan. 27, 1955, the promotion was begun on the Sgt. Preston radio show, and in newspapers.

What started out as a fun way to let juvenile consumers share the romantic notion of owning a piece of gold rush territory developed into a frenzy. Response was so brisk the company had trouble printing deeds fast enough. Nor could it keep stores supplied with boxes of cereal containing the deeds.

And the romance didn’t die. Owners squirreled their deeds away in drawers, safety deposit boxes, albums, scrapbooks and vaults. Even today, the Yukon land titles office, where the file is 45 centimetres thick, receives letters from deed owners asking which highway or airlines they should take to visit their property.

In 1965 the Canadian government repossessed all the land for nonpayment of $37.20 in property taxes. The Klondike Big Inch Land Co. went out of business in 1966.

Memorabilia experts say the deeds now bring about $40 from collectors.