One definition of a consultant is someone who looks at your watch and tells you what time it is. The recently released consultant’s report, Adaptation Roadmap for the SSRB: Assessment of Strategic Water Management Projects to Support Economic Development in the South Saskatchewan River Basin, is a mirror reflecting the aspirations of the irrigation lobby.

In fact, it provides the answer — more dams and reservoirs — instead of dealing with foundational issues.

Read Also

Reconciliation and farming require co-operation to move ahead

Indigenous communities in North America were cultivating crops such as potatoes and corn long before anyone from Europe had heard of the crops.

When facing drought that experts say may persist, moving from supply side management of water and dealing with water demand seems prudent. The real question is how to adapt to less water when supply diminishes.

Adaptation doesn’t happen by building more reservoirs. If this is viable, we may be the first in history to outrun the impacts of a shrinking water supply. No one else has been able to perfect this magic.

Our rivers already have less flow and flows are expected to decline. Reservoirs don’t create water, they just store what is available.

When stuck in an irrigation growth paradigm, it doesn’t register that there is a limit to such growth. The proposed result of this “study” is a classic case of “running faster and faster to stay in the same place.”

There are already 56 reservoirs in southern Alberta dedicated almost wholly to irrigation. Will building eight more be the answer? The irrigation lobby says yes because that’s the perennial answer.

No matter how much lobbying is done and how many new dams and reservoirs are built, climate change cannot be outrun. Even if we bankrupt the province with all the suggested engineering hubris, to the suggested tune of $5 billion taxpayer dollars, this adaptation roadmap could lead to a dead end.

Instead of more holes that may or may not be filled with water, a different path is required.

Proceeding with the exuberance of dam building, without a better understanding of climate change variances, may create enormous engineering white elephants. This also ignores where the water comes from. Our future is likely to be more rain but less snow, but it is slow snow melt that keeps our rivers flowing.

Headwater forests capture that snow, retaining some of it in shallow ground water storage for later release. With our expanding land-use footprint, especially logging, we are changing the way water is trapped, stored and released. This exacerbates floods and drought.

Our forested headwaters are the ultimate “reservoir” for water, yet they merits no attention in this report. Funding upstream watershed restoration and security would seem to be the first thing to consider, not more dams downstream.

This breathless endorsement for more dams and reservoirs isn’t adaptation but a blatant cheerleading proposal for irrigation interests with little in the way of benefits for Albertans, other than a hefty price tag.

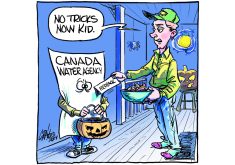

With this report, the irrigation lobby confirms its “adaptation roadmap” will mean our rivers are good — to the last drop.

Shifting a dominant culture and narrative of engineering the landscape for irrigation agriculture to a new perspective of learning to do with less water is a tall order. Difficult, but not insurmountable.

Urgently required is an independent, objective analysis by qualified professionals on the broader questions of how to adapt to a climate change future, perhaps the driest of perfect storms, not how to expand irrigation.

Lorne Fitch is a professional biologist, a retired Fish and Wildlife biologist and a former adjunct professor with the University of Calgary.