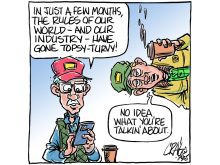

IT IS IN fashion these days for political lobby groups and opposition politicians to demand that government sign onto international treaties or declarations that embrace feel-good intentions.

When governments refuse, as the Stephen Harper government is prone to do, they are accused of being a knuckle-dragging international embarrassment, opposed to causes that are obviously just.

In fact, governments are wise to resist the pressure to sign first and discover the implications later. That is the danger.

Putting the country’s name to a declaration must have consequences. Otherwise, why sign it?

Read Also

Crop profitability looks grim in new outlook

With grain prices depressed, returns per acre are looking dismal on all the major crops with some significantly worse than others.

Last week at a University of Ottawa conference on “water as a human right,” the issue was clear.

The Harper government was castigated for refusing to embrace a movement at the United Nations to have water declared a human right.

How could those mean Conservatives turn a blind eye to the desperate plight of people dying of thirst or forced to rely on contaminated water? What an international black eye!

But even as defenders of the proposed declaration berated Harper’s heartless stance, they had a difficult time articulating what the implications would be for national governments if the declaration took effect.

Could there be lawsuits, on what basis, at what potential cost? Nobody really knew. These are details that will be written once the high-falutin principle is embraced.

Canada has also been condemned because it has refused to sign a United Nations declaration on indigenous rights. But what are the legal, fiscal and economic implications of such a declaration? Refusing to sign until implications for taxpayers are known hardly implies opposition to the principle.

We have been through this before.

A succession of Liberal governments never met a feel-good intention they weren’t prepared to embrace.

Kyoto? No problem, we can figure out the economic and social implications later.

Then there was former Liberal environment minister David Anderson, the west coast tree hugger who probably thought the Canadian Wheat Board was a new environmentally friendly building material – not the current Conservative David Anderson who considers the wheat board to be a human rights blight.

The Liberal David Anderson in the 1990s signed a protocol on trade in genetically modified seed that the Canadian agricultural trade community warned was so vague it set no rules on how importing nations could block Canadian shipments that were not guaranteed GM-free.

Canada signed but never ratified the Cartagena Protocol but enough nations have signed it that it is in effect.

What are the implications? Other than industry uncertainty, the government had no clue.

Almost 30 years ago, conservative advocates insisted the right to private property be inserted in the Canadian constitution.

Since property is a provincial jurisdiction, prime minister Pierre Trudeau was indifferent.

Provincial premiers from right and left said no. What would be the implications for provincial and municipal property regulations or expropriation?

Nobody knew. The provinces were right.

Details please.