THERE is something endearing about the assumptions of rookie cabinet ministers who think their attempts to fix things will win them fans among a grateful electorate.

A few bruising episodes later and they come to their senses. A debrief by Liberal Lyle Vanclief or Tory Charlie Mayer would be in order.

But let’s give them their moment: “I’m from the federal government and I’m here to help. Really.”

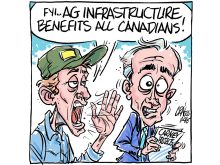

So it was that rookie minister Rob Merrifield, a nine-year House of Commons veteran and Alberta farmer elevated a year ago to a junior cabinet position with tonnes of responsibility, was waxing hopeful about his ability to patch up relations between Canada Post and suspicious rural Canadians.

Read Also

Downturn in grain farm economics threatens to be long term

We might look back at this fall as the turning point in grain farm economics — the point where making money became really difficult.

For the record, Merrifield, 55, is a very nice rural Alberta guy, low-key and gentle in his rhetoric and with no obvious detractors in the hyper-partisan House of Commons after nine years.

On Sept. 12, he went to a rural Ontario town to unveil a Canadian Postal Service Charter that promised continuation of the moratorium on rural post office closings and a commitment not to reduce rural postal service.

“It should alleviate anyone’s fear that we’re going to compromise service in rural Canada,” he said in an interview after the announcement. “We’re not.”

Rob Merrifield, meet Elsie Bedard. No need to call her Mrs. Bedard.

Elsie, meet minister Merrifield.

Elsie is an 86-year-old who lives in West Quebec north of Ottawa and is in a highly public battle with Canada Post over the corporation’s insistence, after 40 years, that her rural route mailbox must be moved for safety reasons.

It is at the end of her farmhouse lane on a dead-end road. But new Canada Post rules that come from a court ruling about the safety of rural mail couriers dictate that her post box location did not meet the criteria.It had to be moved.

“As long as they meet (the rural mail criteria), they don’t give a damn about anybody else,” she complained to a local weekly newspaper in an interview that got her onto Ottawa CBC radio and television.

At first Canada Post said the mailbox should be moved hundreds of metres away, to the side of the main highway, a low area at the foot of a hill where a pond forms in the spring.

“I told them there’s only one place in Canada I know of where water runs uphill and that is in Saint John, New Brunswick (the Fundy tide-driven reversing falls),” she says. “In this part of the country, water runs downhill.”

Canada Post compromised and but still insisted the mailbox be moved across her laneway. She is resisting.

“There’s no need to move it anywhere. It will get run over there by the plows and the tractors picking up our hay.”

At this point, it is a stalemate.

As in many parts of rural Canada, there is anger at Canada Post proposals for change.

Merrifield insists that while there is discontent, the court order must stand and rural Canadians will be protected.

“What we’re doing is locking in charter service requirements,” he said. “They (rural Canadians) can be assured mail will get through in every area of this country.”

If Elsie had been able to get to his announcement, she likely would have disrupted it.