The dust is settling after the April 23 Alberta provincial election, and premier Alison Redford’s decisive victory indicates a shift in the way Albertans see their province.

The new premier is guiding the Progressive Conservative party to the centre-right on the political spectrum. Defeat of the Wildrose Alliance party and its further-right views indicate majority support of that shift.

As the victor, Redford said she plans to position Alberta to drive the national agenda on health care and energy and will reach out to provincial and international neighbours. By contrast, the Wildrose campaigned with more inward-looking policies, albeit important ones, including land use, hospital wait times and MLA wages.

Read Also

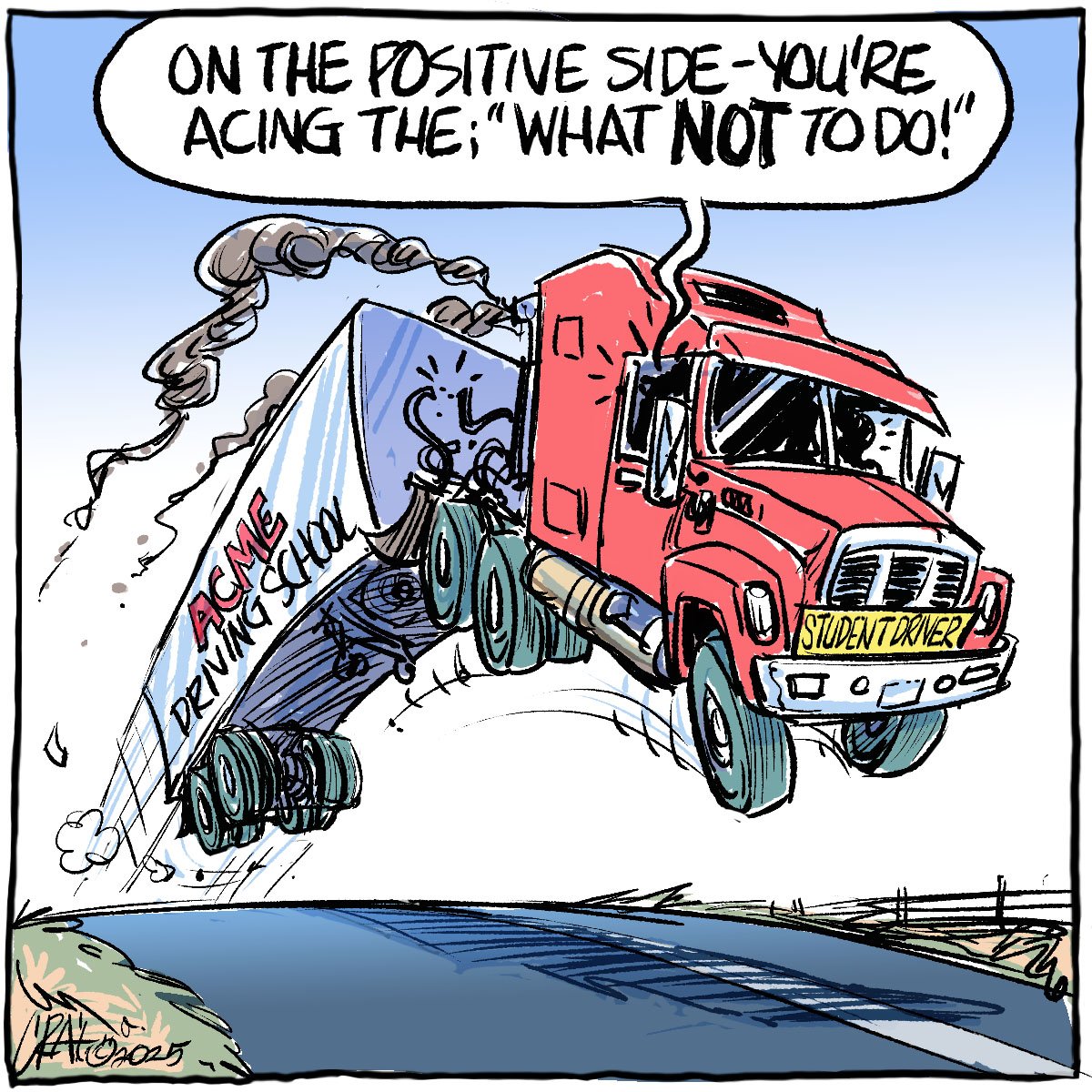

Efforts to improve trucking safety must be applauded

The tragedy of the Humboldt Broncos bus crash prompted calls for renewed efforts to improve safety in the trucking industry, including national mandatory standards.

Given that Redford continues a 41-year PC dynasty in Alberta, it may be hard to swallow the notion that change is coming to a province often unfairly labelled as unsophisticated and even redneck.

However, the election gives Redford a widespread mandate that she hasn’t had since winning the party leadership six months ago, and her direction is not the same as her predecessor, Ed Stelmach, or indeed that of Ralph Klein, Don Getty or Peter Lougheed.

Albertans’ shift toward the centre right is not unlike Saskatchewan’s wholesale support of Brad Wall’s Saskatchewan Party in the past two elections, the most recent one in November 2011. It gave a wide majority to the party born of a Progressive Conservative and Liberal fusion and hence a shift to the centre-right.

Last week, Statistics Canada data showed Alberta and Saskatchewan led Canada’s economic growth in 2011. Alberta surged by 5.2 percent over the previous year and Saskatchewan grew by 4.8 percent. In both cases, strong export demand for natural resources was key.

Now these two provinces, with their generally aligned political views and electoral mandates for at least the next four years, are well positioned to become Canada’s economic powerhouse.

Alberta, forever a “have” province, has been joined by Saskatchewan in recent years. Together, the two have potential to become the drivers of the national economy and, perhaps to a lesser extent, national policy.

But for rural Alberta, particularly southern Alberta, there is now a caveat. The region elected Wildrose MLAs almost across the board, leaving citizens in the unaccustomed position of representation in the legislature by the official opposition. Rural Saskatchewan had a long and sometimes bitter taste of this during the New Democratic government years.

Will the Alberta agricultural heartland have the same clout it had before April 23?

The defining issue in rural Alberta was Conservative land use legislation. Widespread concerns about threats to property rights resonated in the rural south but still aren’t well understood by the governing party’s expanded urban base.

Indeed, the government itself doesn’t appear to have appreciated the depth of rural angst — at least not until it saw the poll results.

The PCs must address this, and presumably they will be pushed to do so by the Wildrose opposition. If they fail, the issue has potential to widen the rural-urban divide.

And that divide bears watching, in Alberta and in every other province. As our population becomes steadily more urbanized, farmers and ranchers may find their concerns receive less attention.

If and when the next agricultural crisis occurs in Alberta, will the Conservatives be there with assistance? Will the Wildrose Alliance, which campaigned for smaller government and individual independence, fight for remedy?

Given the new look of the political map, attention to the widening rural-urban divide will be key to the future success of Canada’s new economic powerhouse in Alberta and Saskatchewan.