Bison have one of the best immune systems of any livestock or game farm animal.

However, they are susceptible to malignant catarrhal fever and have a low tolerance of internal parasites, both intestinal and lungworms.

This predisposition is exacerbated when there are high stocking densities and no rotational grazing.

In many cases, bison slowly go downhill, losing weight and becoming weak with no other real clinical signs.

Even if worms are discovered, the condition may not be reversible if the weight loss is too great, and death follows.

Read Also

Worrisome drop in grain prices

Prices had been softening for most of the previous month, but heading into the Labour Day long weekend, the price drops were startling.

Most deworming products don’t carry a label for bison so they generally require a prescription from a veterinarian.

First, determine whether your bison need deworming. Keep in mind that parasites are smart beasts and release fewer eggs in colder winter months, giving false lower egg counts. Spring and summer are the best times to check.

The best way to determine if parasites are becoming a problem is to check a number of fecals. Up to 10 percent of the herd provides a good cross section. Animals faring below average, especially younger stock, will have a higher worm load so collect a sample – a handful of manure in a container or obstetrical sleeve. Always have a collection device with you so that a fresh sample can be collected when the opportunity arises.

If you know the tag number of the animal, write it on the sample.

Animals performing below average act as sentinels in the herd and can alert us to the fact that a parasite burden is becoming a problem.

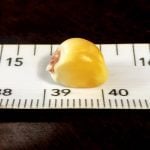

For intestinal worms, I use the Paracount-EPG kit, which was designed for horses but works nicely for bison.

There are a number of species of internal worms whose eggs are similar. The most important issue is to determine if parasites are present. Veterinarians can identify six broad categories (strongyles, nematodirus, tapeworm’s ascarids, lungworms and coccidiosis) and this may help them suggest changes in management practices or deworming strategies.

This quantitative objective test is repeatable in a trained technician’s hands and allows us to compare samples and determine whether deworming strategies are working.

Ideally, the count should go to zero after a good deworming. Natural resistance to parasites can develop but only if the egg count is low initially and parasites don’t become overwhelming.

We see on postmortem the damage worms can do, especially to the abomasum, or fourth stomach. It is easy to see how nutrients are not absorbed properly. When the damage is significant, young and old bison slip past the point of no return.

Lungworms can also cause significant losses in bison in summer and fall, producing a poor performing group with rough hair coats, coughing and diarrhea.

A test called a Baerman technique determines if the larval stages are present. Most veterinary clinics test this in house. Treatment is necessary if even one of these larva is present. Generally, we see lungworms later in the summer.

Most producers deworm when processing in the fall.

The injectable and pour-on products seem to be effective. Some brands are less effective against lice, but that does not appear to be a big problem, at least in my area. Ensure that the pour-ons are worked down into the hair. Absorption seems excellent with the large number of hair follicles bison have.

If treatment was missed in the fall and winter or if fecal tests reveal a worm load, we face the problem of treating in the summer – how do we get product into them?

If the herd is not too big, producers can familiarize their animals with grain as a treat fed in troughs, although it is important to allow room for all to access. They could also use rubber belts laid on the ground to contain the grain and allow access.

Slip in Safeguard (fenbendazole) at twice the cattle dose and in a few days producers should get good control of internal parasites and lungworms.

Fenbendazole can also be mixed in the mineral to be consumed over seven days, but although this works in cattle, mineral and salt consumption is hit and miss with bison. I would stay away from this approach if possible.

Keeping on top of parasites will work wonders on overall health because parasitized bison are more susceptible to other diseases and weight gains are greatly reduced.

Perhaps in the future more soluble products will be developed for use in water or as feed additives. For now, let’s make the best use of the products we have at our disposal.

Roy Lewis is a veterinarian practising in Westlock, Alta.