Glacier FarmMedia – With all the global air temperature records that have been set over the last couple of years, record warm global ocean temperatures have almost slipped by us.

I have mentioned it a few times over the last couple of years, but I don’t think I have given much coverage on this topic.

When you think about it, a lot of implications arise from increased ocean temperatures, including the significant increase in ocean evaporation, which, thanks to a question from one of our readers, is this week’s topic.

Read Also

Canola oil transloading facility opens

DP World just opened its new canola oil transload facility at the Port of Vancouver. It can ship one million tonnes of the commodity per year.

When you think about it, our oceans cover more than 70 per cent of the Earth’s surface and act as a massive heat sink, absorbing more than 90 per cent of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases.

As ocean temperatures rise, the rate of evaporation also accelerates, injecting vast amounts of water vapour into the atmosphere.

This may seem like a small shift in what is seen as a natural process, but the consequences can be big. Increased evaporation is fuelling stronger storms, altering precipitation patterns and amplifying climate feedback loops that may be driving further warming.

So, what exactly is happening beneath the waves, and how is this surge in evaporation changing the weather around the world?

At its core, evaporation is a simple physical process: when water molecules gain enough energy, they break free from the liquid and enter the air as vapour.

However, in the vast expanse of the ocean, this seemingly minor process plays a dominant role in shaping our weather and climate.

The warmer the ocean, the faster evaporation occurs. This is because, as I stated earlier, heat increases the kinetic energy of water molecules, making it easier for them to escape into the atmosphere.

If this was the only variable to take into account, it would be easy to model and figure out what is going on, but wind speeds, air humidity and pressure differences also play a role in evaporation rates.

According to the data, since the late 19th century, ocean surface temperatures have risen by about 1.1 C with even faster warming in some regions. It means today’s oceans are evaporating at a significantly higher rate than they were just a century ago.

However, that’s just the beginning of the story.

More evaporation doesn’t just mean more water vapour in the air. That increase in atmospheric moisture is transforming weather patterns, fuelling extreme storms and setting off powerful feedback loops that appear to be accelerating climate change.

Primarily, rising global temperatures drive the rapid increase in ocean evaporation. The most effective way to slow this process is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and limit further warming.

Unfortunately, ocean temperatures will likely continue rising for decades, even if emissions were cut to zero today, which we know is not going to happen any time soon.

In fact, with the current environmental trends that our neighbours to the south are taking, it is beginning to look like it will be a while before that happens.

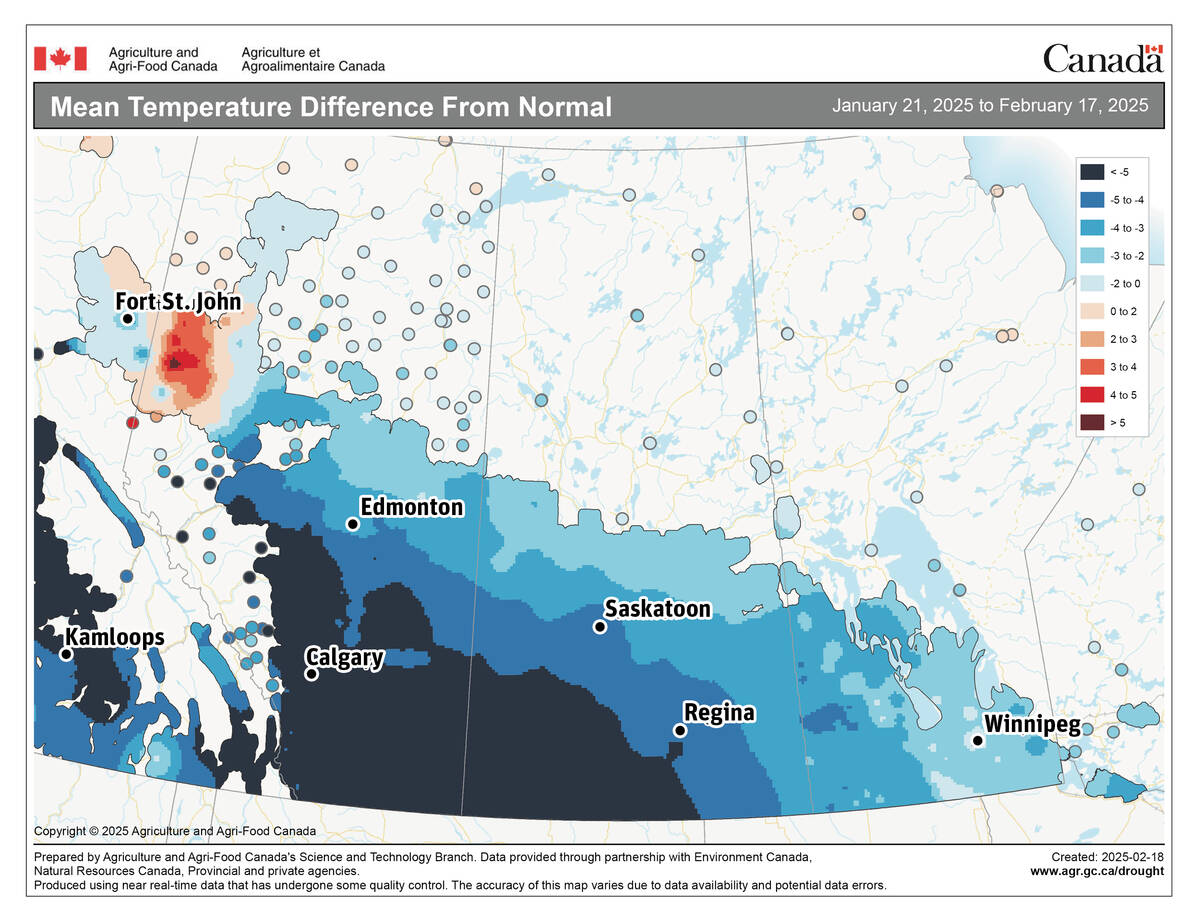

Next week it will be time to take our look back at February’s weather — my guess is that it will be a colder than average month.

Daniel Bezte is a teacher by profession with a BA in geography, specializing in climatology, from the University of Winnipeg. He operates a computerized weather station near Birds Hill Park, Man. Contact him at dmgbezte@gmail.com.