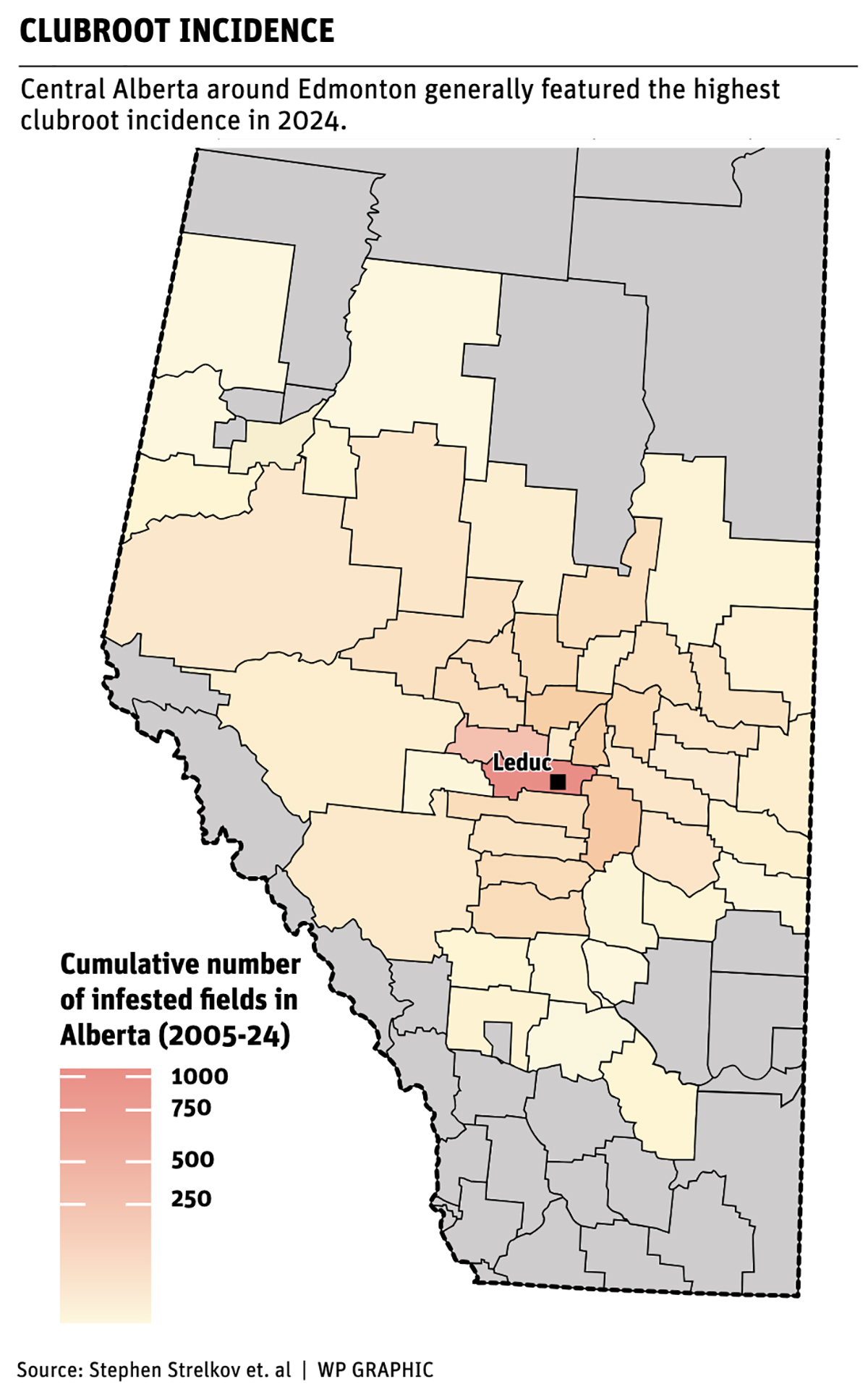

With patchy wet conditions throughout the province, clubroot came out in force in Alberta in 2024. Its favourite targets were in a pocket of municipalities around Edmonton.

These “hot spots” included the counties of Leduc, Parkland, Sturgeon, Strathcona and Camrose — all areas with a consistent history of clubroot.

However, the canola disease was found in more moderate numbers as far north as Clear Hills and Northern Sunrise and as far south as Newell, said Kendra Reimert, an agronomy specialist with the Canola Council of Canada, emphasizing the numbers are based on incidence rather than severity.

Read Also

Protect your grain quality before you harvest

Information on how Canadian farmers can avoid penalties and market headaches by following labels and talking to their grain buyers.

“When they’re checking these fields, they are just looking to see if the clubroot is present in that field or not. So when we’re seeing those hot spots, that would just be based off of the cumulative number of infected fields,” she said.

A 2024 province-wide survey by the University of Alberta and the Alberta government identified clubroot in 47 counties and 307 canola crops.

A total of 691 fields were surveyed. Of those, 167 cases of clubroot were found in fields with no prior history of the disease, according to data provided by Stephen Strelkov and colleagues at U of A.

So what does that mean for the crop disease in 2025? Not much, said Reimert.

Clubroot is highly dependent on environmental conditions that are impossible to predict.

“Typically, clubroot prefers those wet conditions early on in the spring, and then wet conditions in the fall as well, to have that spore population show up for the following year.”

Although parts of Alberta received significant moisture in the spring, particularly on its northeastern side, Reimert said wet conditions in the fall were hit-and-miss with conditions trending toward the dry side.

“So at this point, it would be too early to tell and dependent on the grower’s best management practices. If they’re working with genetic resistance, sometimes that clubroot can be undetectable in some fields, even if we do have those environmental conditions.”

There are no chemical control options for the disease.

Producers who had clubroot in 2024 likely still have it thanks to its tendency to overwinter as resting spores, said Reimert. However, that opens an opportunity for mindful crop rotation decisions in the coming growing season.

“Select a host that’s not susceptible, whether that’s cereals, peas — anything basically but canola — and manage your volunteers if you have any volunteer canola or any other type of susceptible host — which can include weeds such as stinkweed — to make sure that those are managed properly and limit that spore load increase in the following year.”

The most reliable way to confirm clubroot, said Reimert, is to pull plants and look for galls.

Clubroot DNA can also be found by lab-testing soil and plants at select laboratories throughout Western Canada, but the variability and “patchiness” of clubroot make it difficult to determine the spore load across a field, which is a key measurement of disease severity.

“Many labs offer a detection (PCR) test on whether clubroot is detected in the sample or not.

“The other test is a quantitative detection test (qPCR), which will provide the number of spores per gram of soil. Variability of clubroot in the soil, sample size, location, number of cores and handling samples can influence these results.”

Severe clubroot infections will often present themselves through dead canola patches in wet environmental conditions, said Reimert.

The all-important priority in clubroot management is to keep spore counts low, said Reimert. This can be done by attending to several best management practices:

Scout frequently

To the surprise of few, frequent scouting for clubroot is essential. High-traffic and moisture-prone areas are particularly vulnerable to the pathogen and require diligent scouting, said Reimert.

High-traffic areas can include entryways while moisture-prone areas can include field depressions or fields that are typically more wet than others.

Proper rotation

Reimert emphasized sticking to a minimum two-year break between canola crops.

“If it is high severity, the longer the rotation the better. But we understand that the grower may be limited in their rotations, so just be mindful of that one- in-three-year rotation at a minimum.”

Grow clubroot-resistant varieties

Growing clubroot-resistant canola varieties on every acre of the field is one of the most effective ways to manage clubroot, said Reimert.

“It’s really important for growers just to be mindful, when they’re selecting their seed for the following year, that they do have clubroot resistance built into it. Have a good conversation either with your retailer or agronomist if testing should be done to identify if clubroot is present and (its) severity and which varieties to select.

“This can give the grower better insight on which varieties to select for the upcoming year.”

New canola varieties are regularly listed on the canola council website clubroot.ca. It includes an overview of the clubroot disease cycle, how to identify clubroot disease and a section on the disease testing that is available.

A table listing all the clubroot-resistant canola cultivars registered for use in Canada can be found here, on the canolacouncil.org website.

As well, controlling susceptible weeds such as stinkweed can help minimize clubroot spore release and gall formation on canola plants, said Reimert.

Keep it local

Making sure the soilborne disease stays away from clubroot-free fields — both your own and your neighbours’ — is the second category of clubroot management. Reimert suggests reducing tillage if possible to reduce the spread of soil.

Here are some other practices:

Sanitize equipment

Clean equipment using proper sanitation techniques when moving from field to field, she said. However, depending on its size, cleaning equipment can be time-consuming. In cases where time is of the essence, Reimert recommends cleaning at least the visible clumps of dirt and debris between fields.

Some equipment sanitation techniques include rough cleaning of the equipment by scraping off visible, loose dirt on openers, tires, wheels and frames; pressure washing to remove remaining dirt; using a disinfectant such as a one per cent bleach solution (only effective after the majority of soil and debris has been removed); and saving any tillage in clubroot-infected fields for last. Also, limit working in fields when they are wet to prevent excess movement of soil.

Use patch management

Clubroot rarely infects an entire field. Instead, it tends to cluster in patches.

“So, from a patch management perspective, stake out those infested areas to avoid traffic in those areas where you know clubroot is already there, control the host weeds in that patch with herbicide management and just make sure (canola plants) aren’t going to seed or have galls form on them.”

Try lime, seed grass

Although it has been found in alkaline soils as well, clubroot tends to favour acidic soils. Hydrated lime can help gain soil alkalinity.

“There has been some research done in those highly acidic soils that (show) you can apply lime until that soil pH reaches around 7.2 to 7.3 to reduce the gall formation on some of the canola varieties,” said Reimert.

If all else fails, seeding an infested patch to grass may help minimize soil movement.

“You can break up that grass and crop that area again once the spore loads are lowered based on annual soil testing, but … how long that grass is seeded down for will depend on the level of infestation.”