A group of North Dakota farmers wants to build a $40 million oat processing plant in the United States and they’re inviting Canadian farmers to become members of a new-generation co-operative when they hold an equity drive in February or March.

Two representatives of Oat Technologies visited the annual meeting of the Prairie Oat Growers Association, held in Winnipeg last month.

Oat Technologies wants to extract the various minor components of oats to sell into high-value niche markets.

Randall Meidinger, the chair of Oat Technologies’ interim board, said he hopes construction of the plant will begin in June, with completion in time for processing the 2001 crop.

Read Also

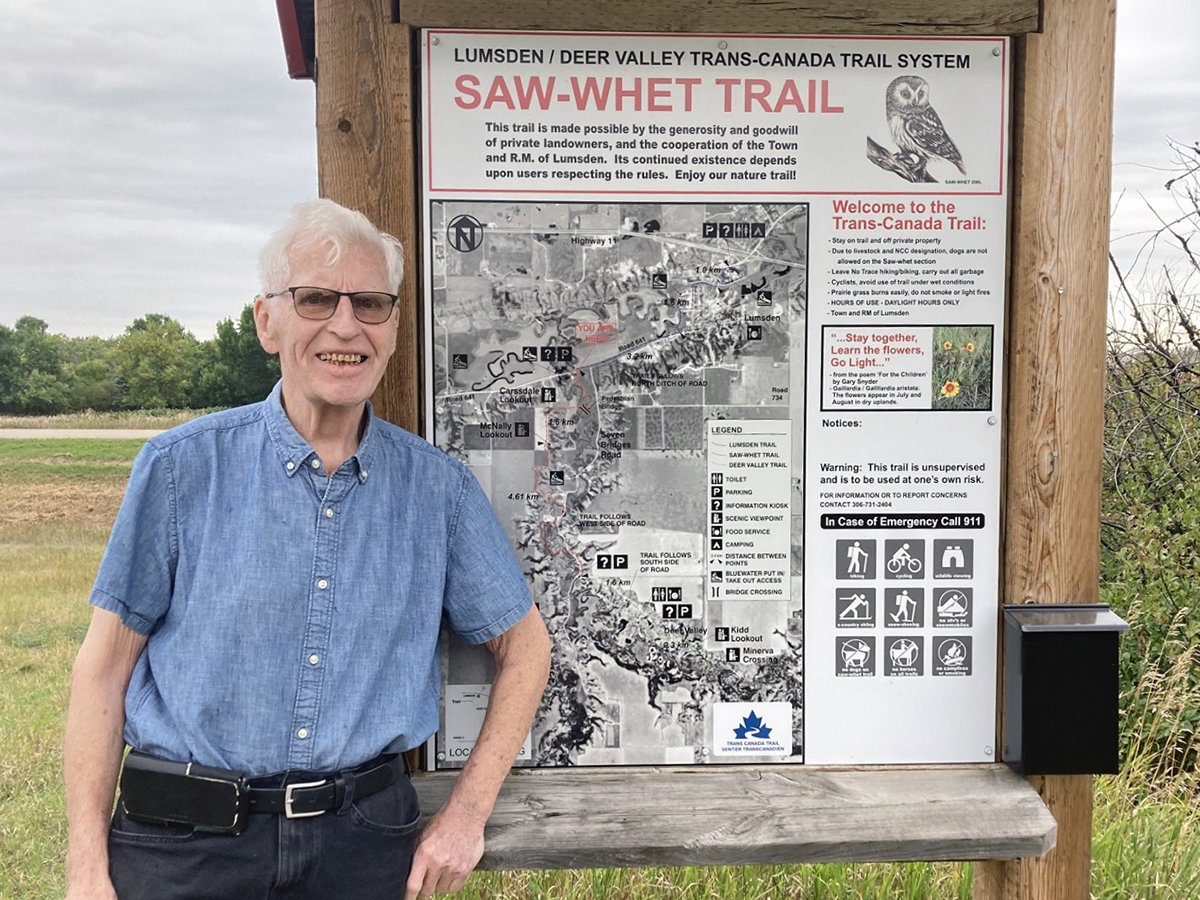

‘Sinc’ remembered for dedication to rural Saskatchewan

A rural Saskatchewan leader instantly recognized by just his first name is being remembered for his dedication to the province.

Meidinger said the group wants Canadian farmers to supply up to half the oats for the plant, which will be located in North Dakota.

“I think this is one of the solutions to the problems in agriculture,” said Meidinger, who farms at Linton, N.D.

Farmers need to become vertically integrated with processors so they might as well own the processing to get better returns, he said.

The Oat Technologies proposal attracted 850 North Dakota farmers to information meetings last spring and about 250 of them were interested in becoming part of the project.

The co-op would need about 51,700 tonnes of oats to accommodate the plant, Meidinger said.

Up to 70 percent of the oats would be traditional types with elevated beta-glucan levels. The rest would be naked oats.

The group forecasts annual revenues of $25 to $25.5 million (U.S.) and hopes to pay farmers up to $2.20 per bushel.

It has also talked to engineers and equipment manufacturers to make sure it can get the equipment needed to process the oat components, said Larry Dawley, a Kansas consultant working with the group.

The plant would make lethicin, sterols, antioxidants, oils, defatted soluble fibre, proteins and starches.

The products would be used in nutraceuticals, cosmetics and industrial markets.

Meidinger said the company would fill niche markets that the large U.S. millers aren’t interested in.

Oat Technologies’ strategy sounds similar to what has been tried by Ceapro Inc., an Edmonton company that sells oat products to the pet food and cosmetics markets.

Ceapro processes oats at the Leduc Food Processing Development Centre. It used to own the now-bankrupt Canamino facility in Saskatoon.

Bob Binnendyk, president of Ceapro, could not be reached for comment.

Oat growers at the meeting seemed to like the concept behind the Oat Technologies proposal.

“I think if we can add the type of value they’re talking about, that would be phenomenal,” said Willy Groenveld, president of the Prairie Oat Growers Association, who farms at Mannville, Alta.

Bob Anderson, a seed grower from Dugald, Man., and vice-president of the oat growers, said naked oats are challenging to handle and store.

Some farmers who wanted to invest in the Prairie Pasta Producers co-op might be interested in the oat co-op, he added. But farmers would need a lot more information before deciding whether this opportunity is right for them.

The project’s timing is not ideal, Anderson said.

“If there was more money around, there would be much more interest.”