American farmers harvested approximately 20,000 acres of hemp in 2022.

That’s not a big number and it’s a massive decline from 2019, when there were 511,000 acres of hemp licenses in America, according to data from Vote Hemp, a lobby group.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture will release official hemp statistics in February, but it’s possible that American hemp acreage declined 2,300 percent from 2019 to 2022.

The catastrophic drop is mostly related to the CBD craze, which lasted from 2017 to 2020. At that time, particularly in 2019, hemp became one of the hottest crops in North America.

Thousands of new players entered the business, hoping to capitalize on a media frenzy and claims that growing, manufacturing and selling hemp CBD would become a massive industry.

They predicted a $10-$30 billion market for CBD, the cannabidiol found in the flowers, buds and tissue of hemp plants.

Some research has suggested CBD oil can treat many health problems, including insomnia, inflammation and anxiety, and help with pain management.

The sales pitch was effective.

Farmers across America planted hemp for the first time in 2018 or 2019, hoping to cash in on the opportunity.

“Before COVID, I was invited to Montana, to Pennsylvania, to New York State. For them, hemp was CBD,” Jan Slaski, a researcher and hemp expert with Innotech Alberta, an applied research organization with a research farm in Vegreville, said in 2021. “(Some) farmers in Montana put all their eggs in their CBD basket.”

The linkage between hemp and CBD proved to be a curse for the hemp industry. In 2019 and 2020, hundreds of American growers got stuck with hemp flowers and buds that they couldn’t sell because demand for the plant tissue didn’t exist, or demand only existed at a price much lower than growers were promised.

The CBD madness wasn’t as extreme on this side of the border, mostly because Canada’s hemp industry was more established and built around producing hemp grain for food.

Still, the CBD hype was a distraction.

“When it started, 2019 was the first crop year that we (the hemp sector) were selling to the CBD market (when it became) legal,” said Clarence Shwaluk, chair of the Canadian Hemp Trade Alliance.

“There was a lot of hype with that. And probably overblown.

“What we’ve seen is that the regulatory pathway to get CBD to consumers is somewhat restrictive, and people in that industry would say very restrictive.”

The CHTA has been lobbying Health Canada so CBD hemp can be sold as a natural health food product. It remains a work in progress.

In the meantime, Canada’s hemp sector has returned to its roots — growing hemp for food and fibre.

“The main target market is that health-conscious consumer, those who are looking for incorporating healthy ingredients into their diet,” said Shwaluk, who is also the director of farm operations with Manitoba Harvest, a food company that contracts hemp production and markets hemp protein, hemp oil, granola and other products.

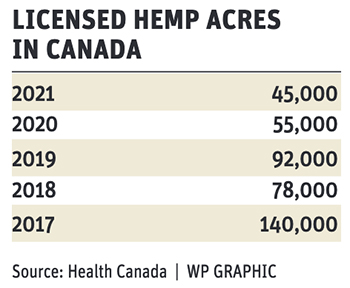

Hemp acres in Canada have declined over the last few years, but may see a small recovery this year. Prices are solid, at around 86 cents per pound for conventional hempseed.

Shwaluk and Manitoba Harvest are looking to increase organic hemp production and in January he traveled to Quebec to recruit some organic growers.

“We’ve got some big retailers on board and creating some big (organic hemp) demand for us,” he said. “On conventional, we had a lower exposure to the market last year. Number one, because of price. Number two, we needed to balance out our (inventories)…. Overall in the industry (acres will be) probably up higher this year.”

Demand for hemp fibre could also encourage more acres.

“Fibre is another thing coming on board across the Prairies, primarily,” Shwaluk said.

“In Alberta there’s a group that’s going to be looking at upwards of 10,000 acres, on fibre only…. A group here in Manitoba is looking at probably the same amount.”